Photo by Barbara Elisabeth Walther

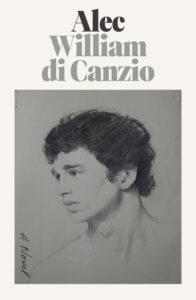

William di Canzio is an award winning playwright and teacher. His debut novel, Alec, is inspired by Maurice, E. M. Forster’s radical gay romance, published in 1971 after the author’s death. Alec continues the story from the point of view of Alec Scudder, a gamekeeper and Maurice’s secret lover. With an immensely brave and sensitive story, Di Canzio beautifully extends the legacy of these queer characters. He honors Forster’s groundbreaking decision to write a queer love story with a happy ending, while also examining the life-changing turmoil of war and separation.

Over email, di Canzio and I discussed his approach to handling this legacy, as well as the themes of mysticism, competition, and eroticism woven throughout his book.

Emily Saso: To start with, what was your journey like in terms of realizing there was a story here? Was there something specific about the character of Alec that made you decide he could carry his own narrative?

William di Canzio: It started with my love for Maurice, E.M. Forster’s seminal novel — the story itself and the skill of the writing.

Also with an instinct that there was more of the story to tell, a hunch confirmed when I read Wendy Moffat’s splendid biography of Forster, A Great Unrecorded History. Forster himself believed there was more to tell. He had tried to write an epilogue, imagining a future for Maurice and Alec, but threw it away. Maurice ends in 1913. The world where the gamekeeper and gentleman fell in love was subsequently destroyed by the Great War, and Forster was stymied.

But with the twentieth century well behind us, I believed I could imagine their future lives, while remaining true to Forster’s vision.

As a playwright, how did you decide that this story should take the form of a novel, not a play?

Plays require a compression of time and place. (West Side Story, for a favorite example, breaks our hearts with the events of a day and a half in a few city blocks.) But for Alec, I needed to span years and nations. A novel lets you do that.

I’m curious about your research process here — did you look to any particular historical figures when crafting Alec?

For Alec himself, I had no particular historical figure in mind. Certain historical figures did shape my presentation of other characters, though: Edward Carpenter, George Merrill, Lytton Strachey, and Forster himself.

In the terminal note for Maurice, E.M. Forster wrote that to him, “a happy ending was imperative.” Maurice, at the time it was written, would have been one of the first gay love stories with a happy ending. Did you feel a certain obligation to give Alec a similarly happy ending?

Absolutely. I’d never read such a story. That’s why we love it.

Forster also wrote in the terminal note that the book is now an unintended tribute to “the last moment of the greenwood”, i.e. an idyllic rural England that was shattered by WWI. How much did you consider the implications of bringing the characters through this loss?

In my novel, Maurice hatches a scheme, before the war, of buying some woodland where he and Alec might live a secluded life together and support themselves. But the trauma of the war devastates nature as well as the lovers. After the war, it seems there’s no woodland left to buy in England.

There’s also emotional development at work. Alec and Maurice mature during the years of the war. They soon realize that their once-imagined “happily ever after” would not have satisfied them for long.

I would venture that a recurring motif in this book is competition — literal athleticism, and competition within relationships. Maurice and Alec are often trying to “win” situations. How much do you see competitiveness as a part of romantic love? Would you say this is related to the class differences Maurice and Alec also struggle with?

In Maurice, Forster calls their competition “toughness and tenderness mixed.” He acknowledges and dives into the vying emotions of love. They hold true for all of us, I believe, especially when we’re young. Maybe competition is intensified in same-sex relationships, but maybe not. In love, don’t we all want to conquer and surrender at the same time? Resist and yield, unite with the other and remain independent?

About class difference: yes, it does factor in the lovers’ contest of wills. Maurice, the gentleman, has been sucked in by the myth of his own superiority, reinforced by his elite education. (In Forster’s novel, he throws up his hands and groans when he learns that Alec is a butcher’s son.) Alec is prejudiced against those who call themselves his “betters.” He is certain he sees through their ignorance and self-aggrandizing. He despises the ruling classes for their airs and delusions and, when he senses that Maurice is turning up his nose, hates him too. It’s a struggle for both of them.

Can you talk through your decision to sometimes repeat exact passages of dialogue from Maurice? Was it a choice of function, or do you think something specific is gained by looking at these words a second time?

The fictional world of Alec accepts the events of Forster’s novel as fact. In Part II of my novel, the action coincides with that of Maurice. When the lovers are on stage together there, I quote Forster’s dialogue, because that’s what they “really” said. At the same time, I adjust the narration to accommodate Alec’s point of view.

Maybe a useful comparison would be Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. When the action of Tom Stoppard’s play intersects with Hamlet, Stoppard quotes the original dialogue, because that’s what they “really” said.

I’m very thankful to the Forster Estate, whose trustees at King’s College, Cambridge, reviewed the manuscript of Alec in advance and permitted the quotations and adjustments.

Forster wrote that he became “annoyed” by the character of Clive Durham, Maurice’s first almost-lover. He is nearly entirely absent from Alec. Did you ever consider including him in the narrative?

In early drafts of Alec, Clive had a bigger role than he does now, with a subplot involving his wife and a postwar scene where he sat in judgment, as magistrate, of a man arrested for having sex with another man. In the course of revision, what I was writing about him seemed bloodless compared to the story of Maurice and Alec, so I cut most of it.

Alec outshines Clive. As soon as Alec enters the story, Clive diminishes in importance to Maurice and us readers. I do understand Forster’s annoyance. Clive is part of an old order, a self-serving structure of class and power that needs to go.

Forster is often criticized for a tendency to write clumsily about sex, or avoid it entirely. In Maurice, sex is shrouded in an oblique and not particularly erotic manner. Your book, however, contains numerous love scenes. How did you approach in some ways “uncovering” what Forster would or could not write?

When he first wrote Maurice, in 1913-14, Forster, in his mid-thirties, was sexually inexperienced. So there’s lack of knowledge to factor. But I also believe that pre-war esthetics would have inclined him to be reserved when writing about sex, and especially because both lovers in Maurice are men: in England at that time their lovemaking would then be judged “criminal” and “unnatural” and “unspeakable.”

When he revised the manuscript — twice that I know of — over the ensuing decades, Forster had certainly gained sexual experience, but sex between men remained a crime in England until 1967, three years before his death at 91.

Or maybe, for artistic reasons, Forster judged the vagueness, even awkwardness of the love scenes to be true to his hero, Maurice, who is still quite young, just turned 24, when the action ends. It’s a guess.

On the other hand, it is Alec who awakens Maurice to the full power of erotic love. His gift to Maurice is not only his body, but the awareness and confidence about his nature that he was blessed with at an early age.

About “uncovering”: when my novel presents a scene from Forster, I do so from Alec’s point of view, and that’s informed by his passion and his courage.

There is a certain amount of mysticism in both Maurice and Alec — significant dreams, meaningful encounters with animals, clairvoyance, and possibly ghosts. Was this an area you had explored previously in your work? If so, did you find there was a difference when writing about these elements for a novel versus for the stage?

You just sent me into a mental review of my plays, and I’m surprised at how many ghosts (and gods) appear in them. Sometimes they speak, sometimes not. I’ve never written one like King Hamlet or Clytemnestra in The Furies, where the ghost is spooky and wants revenge. My ghosts tend to embody what the living characters are feeling. That’s pretty much true in Alec as well.

A difference between fiction and stage would be that, in a play, the audience see (and hear) the ghost. But in Alec, we learn about a ghostly presence not from the narrator but from a character, whose objectivity may not be reliable.

About clairvoyance, there’s a certain sad historic truth in Alec: i.e., after the Great War, bereft families might seek to communicate with their sons killed in battle through a spiritualist.

As for the dreams in the novel, they’re mostly shaped by the veterans’ PTSD.

I’m glad you noticed the animals! The first time I saw a pileated woodpecker — in the woods; it was enormous — I thought it couldn’t be real, it must be mythical, like the phoenix. And just the other day a neighbor was leading a miniature pony down the sidewalk in front of our house — out of nowhere. It stopped me dead, like the vision of a unicorn. Alec spent three years of his young life tending birds and animals as a gamekeeper. He’s especially attuned to their power.

I might be reaching here — but is the character of Morgan based on E.M. Forster? His middle name was Morgan, he similarly lost his virginity late in life while in Egypt, and he was a scholar.

Yes, the character of Morgan is based on E.M. Forster, including his teaching at the Working Men’s College in Alec. Also Forster was friends with Edward Carpenter and George Merrill, whose relationship across social classes was his model for that of Maurice and Alec, and who appear as characters in my novel. (I call them Teddy and George.) But while these characters share some elements of life with historical models, I don’t equate them. Their fictional lives are their own.

I’m curious why you have them emigrate to America at the end of the novel, instead of, for example, another European city. Does that reflect a certain amount of hopefulness about this country?

From the start of the project, I was always certain about two things: the title and the ending. They’re heading for New York, where, for better and worse, a new age is being born.

Alec

Alec

By William di Canzio

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

July 2021

Emily Saso is a writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in Bellevue Literary Review, LitMag, and Harpur Palete. She was the recipient of a New York State Summer Writers Institute Merit Scholarship. She currently works at Columbia University in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

This post may contain affiliate links.