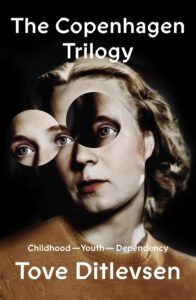

[FSG; 2021]

Tr. from the Danish by Michael Favala Goldman

“Time passed and my childhood grew thin and flat” writes Tove Ditlevsen in the first book of The Copenhagen Trilogy, a memoir of the acclaimed Danish author’s life, recently released as a single-volume English translation. “It was tired and threadbare, and in low moments it didn’t look like it would last until I was grown up.”

Ditlevsen’s childhood would, in fact, last her into adulthood, though not without enduring considerable wear and tear. In unsparing, unsentimental prose, Ditlevsen — already well-known in her native Denmark and now making a posthumous splash in the US — describes her impoverished upbringing and her struggle to write in the creative isolation of her environment, before eventually achieving literary success. Ditlevsen grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Copenhagen, with her father, a frequently unemployed laborer, her mother, who stayed at home, and her older brother. As a child Ditlevsen was sometimes hungry, anemic, and underweight, her teeth damaged by malnutrition-induced rickets, and she attempted suicide at the age of twelve. Her family was unable to afford to send her to high school and she instead worked a series of manual labor jobs, and then office jobs, before eventually marrying and publishing her first book .

It is not easy for writers of Ditlevsen’s background to make their way to the page, but those who do can find themselves ensnared in the difficulties of their early life, even as they’ve left it behind for literary fame. After her difficult childhood and adolescence, Ditlevsen was married four times, and had four children. Her memoir describes her struggle with opioid addiction and her psychiatric hospitalization. Critics reading Ditlevsen’s work will dutifully make reference to her working-class roots, but seem unwilling to consider what impact these experiences might have had on her as a young writer. Perhaps this is because fame came relatively early for Ditlevsen, implying a kind of meritocratic inevitability to her success, and rendering her early life simply a strange and sad introduction to her real role as a chronicler of the Danish soul. But even after her first break into the industry — a book of poems and then a novel facilitated by her much-older husband — her transition to a life of middle-class comforts was far from seamless.

After her first marriage to Viggo F., an editor and writer with a day-job at a fire insurance company, Ditlevsen became preoccupied with the class incongruities of her new life: the condition of her clothing at parties, a persistent sense of unease and out-of-placeness, and insecurity about her lack of formal education. She describes the shower in her new husband’s apartment (a first for her), his captivating green glassware, and the maid that helps them with housework.

Ditlevsen’s discomfort has to do with not only a change in income, but with the possibilities of creative self-actualization that income allows. She’s struck by how casually Viggo F. asks her whether she would like her poems to be published: “He says this as if it were nothing special. He says this as if it were quite common for me to publish poetry collections; as if it weren’t what I wished for, most fervently of all, for as long as I can remember.”

The question of what might be possible is always being asked, first plaintively in childhood, and then continuously expanding to include ever-larger possibilities into her adulthood. But even as she succeeds, Ditlevsen appears darkly resigned to the inescapability of her early life — the lingering “bad smell” of childhood.

There is an eerie feeling one sometimes gets while reading a memoir; though the author reveals their life in neat volumes, the reader has special knowledge of how things will really end. After one early rejection Ditlevsen expresses her fear that she’ll need to compromise on her creative dreams and resign herself to the expectations of the working-class life she was born into: “I’ll never be famous, my poems are worthless. I’ll marry a stable skilled worker who doesn’t drink, or get a steady job with a pension.” The reader knows that none of these fears come to pass, Ditlevsen does become famous and earns a sizable income of her own, but her romantic life is far from stable or sober. (In another one of Ditlevsen’s books, a novel, she describes a writer who overdoses on sleeping pills and wakes up regretful. Ditlevsen would eventually die by suicide after ingesting sleeping pills).

Though it was marriage that helped pull her out of the working-class and into the literary world, her third marriage, to a doctor named Carl, eventually leads her down a dangerous path. After beginning an affair and becoming pregnant, Ditlevsen asks Carl to give her an abortion. He uses the opioid Demerol as an anesthetic thus beginning a long battle with addiction, enabled and supplied by Carl who provides her with injections whenever she requests them.

The toxic mix of marital obligation and addiction prompted the original Danish title of the third and final book of the series, “gift” meaning both “poison” and “marriage” in Danish, artfully translated into “dependency” in Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman’s English translation.

Ditlevsen’s success is remarkable not only because of her class background but because of her gender. Though her relationship with her mercurial mother is a source of suffering for Ditlevsen in childhood, she is haunted by several men throughout her life with artistic dreams of their own. First, her father, who loves to read and worked briefly as a journalist before being forced to quit (and who tells her, when she is just a girl, that women cannot be poets), her first husband who is considered a stuffy and parasitic writer by his peers, and then her second husband, Ebbe, who wished to study literature in university before being persuaded to pursue something more practical by his father. None are able to match her in talent and success, despite their advantages.

Ditlevsen is candid about the personal toll that the claustrophobic poverty of her early life had, though she does not extend this to any type of broader political argument. Though her family explicitly align themselves with the social democratic party, read socialist books, and appear steeped in an understanding of their class identity, Ditlevsen’s view is somewhat more individualized. Perhaps the connections between these early experiences and her troubled later life were meant to be obvious. If so, she might be surprised to find that many of these same challenges of the literary world — economic precarity, classism, insularity — persist today.

Writing, as a career, is still best suited for those with money and status. For the poor or working-class, the noise of self-doubt, rejections, and hardship synonymous with a writing career are ratcheted up even more, sometimes to an unbearable degree. For working-class writers, the nuts and bolts are always showing, they do not slip into their role naturally through pursuing their own whims, lubricated by social connections, and easy confidence, as writers from wealthier backgrounds do. But though her success was hard won, Ditlevsen is not intent on making herself into some kind of noble example. Her novels, poetry, and memoirs are only concerned with expressing the specific experience of one female twentieth century writer: herself. And her work — the whole point after all — is probably stronger for it.

Sejla Rizvic is a writer in New York City.

This post may contain affiliate links.