[Ablucionistas; 2020]

Tr. from the Spanish by Fer de Luz

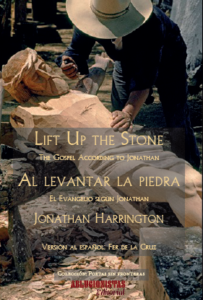

Set in the present-day Middle East against the backdrop of conflict in Israel and Palestine, Jonathan Harrington’s Lift Up the Stone is a sequence of 40 sonnets retelling the Gospel of Matthew. It is a world where jet fighters scream over the Gaza Strip while the Three Kings on camels follow a distant star. (“At first we thought it was a satellite.”) Mary and Joseph’s flight into Egypt finds them “picking their way / through mine fields, dodging searchlights, bomb craters.” Idiosyncratic and sometimes startling, these poems demonstrate both the elasticity of the sonnet form and the meditations of a fertile, original mind.

The author grew up in Florida, studied poetry at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and later lived in New York. After publishing several novels, he moved to Mexico, where he has resided for many years. In addition to his own work, he also translates poetry from Spanish and Mayan. This volume is a bilingual edition, in English and Spanish, with the latter versions credited to the translator Fer de Luz. This review will focus on the English texts.

Constructed in three acts and an epilogue, Lift Up the Stone relies on many voices. Most of the sonnets are dramatic monologues recounted from the point of view of familiar biblical characters and their non-canonical supporting cast. Thus, in addition to Mary, Joseph, and the disciples, Magdalena and Pilate, and a memorable cameo by Satan, the reader also finds the observations of hangers-on and bystanders, the loafers at the barbershop and a down-and-out drunk. All are perplexed by the strange events set in motion by Jesus. Some mock, others ponder. And there is a dog who “settled back and just enjoyed / Your sandals rubbing gently on my belly.”

Unorthodox, yes, but while these poems include flashes of humor, they avoid slapstick or Pythonesque spoofing. What generates energy is the poet’s specificity. Anyone who’s tried to read the Gospel of Matthew begins with the frankly tedious chapter tracing the origins of Jesus back to Abraham. The speaker in the first sonnet, “Genealogy,” remarks on this difficulty:

Forgive me, please, if this is blasphemy.

It’s not . . . at least not meant to be.

It’s just — so many names and so few faces.

[. . .]

Were they good dads or guys like me who do

their best but not enough? You understand?

I know my father’s name but not the man.

Lift Up the Stone takes pains to particularize, to provide faces to everyone it names. Most of the sonnets are conversational in tone and seductively “easy” to read, though full of sly allusions. Harrington isn’t averse to rhyme or the occasional closing couplet, but he uses rhyme sparingly, preferring a flexible blank verse. Above all, he is curious about story. The gospel account, which will be familiar to most readers, serves as a template upon which he can elaborate or reinterpret his characters, often in light of the updated setting.

For example, in “Little Children,” Jesus’ well-known rejoinder to his disciples that children are “the greatest of us” is here contextualized to include youths outside Jenin who throw rocks at passing tanks, only to be dispersed by tear gas. In “Last Supper,” the famous communion invitation to share body and blood is dramatized not as trans-substantive or symbolic, i.e., metaphysical, but as a literal reality, with reference to an organ transplant in which the kidney of a Jewish teenager killed in a suicide bombing in Tel Aviv is given to a Palestinian girl. Elsewhere, the reinterpretation is less topical, emphasizing the raw emotions of individuals. In “Miracle,” an unnamed speaker who saw Jesus heal a blind man questions whether this act was a blessing or a curse. Why would a person want to see “the maimed, bruised, tortured world”? In “The Good Thief’s Sister,” the sibling of the thief crucified alongside Jesus is unimpressed by the promise of redemption:

I heard You forgave him as he hung there.

What a joke — he was a con man to the end.

I don’t care what You say, I don’t forgive

him. He was a prick. I hope he burns in hell.

“Incident in the Temple,” about Jesus expelling money changers from the Temple, offers contradictory accounts, some “off the record,” about what really happened that day. Did he really overturn tables? Was a banker right to sue for damages? Who to believe? This questioning mode animates much of Lift Up the Stone, reflecting an awareness that stories easily become slippery. This is wonderfully illustrated in “Satan Tempts Christ,” where the slipperiest character of all confronts Jesus in the desert, in the guise of a land developer:

Check out this view: now that is real estate.

Where you see desert, I see subdivisions,

or rows and rows of condos all for sale.

[. . .]

It’s Yours; ain’t no one there but ragheads;

it’s fucking desert dude; it’s up for grabs.

A few poems, like “Vigilante,” with its child’s eye view of adults engaging in mob violence, lack this defamiliarizing force, while “Puppet Master,” about a bizarre board game with wind-up soldiers called “Crucifixion,” veers to the other end of the spectrum and is difficult, at least for this reader, to decipher. But on the whole, Lift Up the Stone is impressive for its range and invention. The subtitle, The Gospel According to Jonathan, asserts its place in the tradition of artistic reimagining of a foundational narrative, and this place is earned.

To a degree, Harrington’s sensibility reminds me of Kurt Vonnegut’s remark, “If it weren’t for the message of mercy and pity in Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, I wouldn’t want to be a human being. I would just as soon be a rattlesnake.” But, as Harrington underlines in the Epilogue, this message is not fixed in time. Rather, it is part of an ongoing search. In reference to the traditional story of the Ascension, the speaker observes, “your final miracle [was] a disappearing act.” Despite this,

I still look for you in the crowded streets,

among the homeless sleeping on the sidewalk

beside their shopping carts of rags and cans.

Could one of them be you?

[. . .]

When I am almost overwhelmed by despair,

I think of your words: “Lift up the stone,”

you said to us one day, “and you will find me there.”

The book brings that search to life, in ways both bold and subtle. It does not offer easy answers, but this probing restlessness is a major source of its strength.

Charles Holdefer is an American writer currently based in Brussels. His work has appeared in the New England Review, North American Review, Chicago Quarterly Review and in the Pushcart Prize anthology. He is the author of nine books, most recently AGITPROP FOR BEDTIME. Visit him at www.charlesholdefer.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.