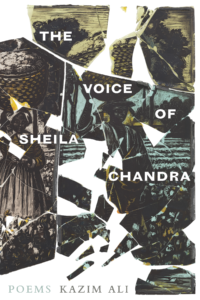

[Alice James Books; 2020]

Writers negotiate their own relationship to silence — as canvas, as collaborator, as agent to frame or defy or defile. They may be reverent toward that which bears speech and may be humbled or stirred by the possibilities it contains. Poet Kazim Ali’s new book, The Voice of Sheila Chandra, kindles the music inherent in language with solemn invention, and it is tuned by a repercussive conceptual silence. Belief and its mutability thrum through an ambitious triptych of poems separated by interstitial pieces driven by sound. The project attends to expressive orbits of protest, grief, and song. It seeks mystical synthesis as a choreography of silence and gesture. A body is an instrument of fate and physics.

The titular poem honors the speech and song idiopathically revoked from musician Sheila Chandra. She’d evolved from a pop music star of the 1980’s and 90’s into a drone style solo performer before she suffered an onset of Burning Mouth Syndrome. Drone, a musical form wherein the voice offers every tone in a resonant expanse, is sounded in collaboration with silence. One conceptual core of this poem is a kind of listening that brings both the speaker and reader awake. “Sheila’s voice always in the background /Always disappearing into the music / Of what surrounds it the way one loses / Oneself in sex or death or the moment / Of shitting . . . ” Here, the intimate confluence song makes of body and spirit is drawn with a lyric bluntness. This sequence in the book is made of forty sonnets, an offering to the musician by way of personal and philosophical weavings across art, the personal, and the political. Composing self across these inputs, as though identity itself were palimpsest, Ali draws the reader close, avowing presence and affections, while the lines that follow may rightly fling us so as to “echolocate God.”

Here, the poetic line wields its power through blur of fragment, grammatical syntax, and non sequitur. Ali’s three focal poems unfurl distinct measures and rates of comprehension — every piece stands unpunctuated. A thrill. And generous. One can savor all the slippage or suspension of meaning that extends through each sequence. “To hear is to make real,” opens a central concern of the book: Sonics, reverb, echo. Ali attends closely to articulated music of poems spoken, and simultaneously tunes to inner machinations of brain voice, as the poems are thought through, just as “real” in the reader’s mind. The conceptual, rhetorical, and imagined structures of the lyric hold as much pleasure and wisdom as the uttered line.

“Hesperine for David Berger,” the first long poem in the book, imagines that a curse may be drawn as a gesture of aspiration. It is an invented form evoking the “evening star,” Venus. The sequence of indented mono-stitches maps protest, fidelity, sport, political violence, and creative acts that wind agencies of grief into the world. “There is no tradition in the literature of the world of the hesperine not a serenade nor an aubade but rather a curse to first darkness itself begging it not to fall a poem against falling of night to ward off death.” The mold of this poem nominates the page as site of reverent inscription, creates monuments scaled to a broken body. The poem bows to moments once-intimate-now-historic, transpiring on a continuum of creation, destruction, remembrance. “Can we sing over the noise or paint down on the stone once marked by flesh and death can we move forward without breaking” (Ali’s proposals ring out further sans punctuation.)

The interstitial poems that open, partition, and fasten the book are concentrated detonations of sound-sense. They are not resting points in the book so much as an opportunity for the reader to reorient oneself through the playful sonic pleasures of poetry. An opportunity for grounding, deepening, preparing the reader for the next imminent music.

The third long poem is “Phosphorus,” a multivalent text that tests the verticality of personal myth, loneliness, and hero’s journey — all under the guise of starlight recast as the presence of the planet Venus. The poet plumbs “spectacular confluences of historic possibilities” and chosen mythologies. He sprints towards the query: “ . . . what if/Sound was a metaphor for something past it” and innovates the container of his language even in order to express the puzzle of aspirations. Interspersed between the five-line stanzas, blocks of text that are four-letters-thick trundle down the page in a formidable column. Such gestures are monoliths to be deciphered, almost as though creating the meaning of a new constellation in a sky of a million stars drawn together. Orpheus and his song composed prone, projected into the earth, figure prominently in this poem as a counterpose to the celestial rumination. Ali entreats Orpheus’s “actual syllables” in the hopes of understanding the material reality of the figure’s passage into the underworld.

A poetics invested in spirit, Ali’s invocation of silence is not neutral. It emanates from what T.S. Eliot called “third voice,” dramatic persona that enables speech beyond the personal. It is grief-specific, opening up and outward, and indebted to the physiological mislay of Sheila Chandra’s music ruined as though by burning. Her legacy gives way to an audacity in this collection, as time swifts before and after injury and percusses a spiritual plane. These poems acknowledge how the voice is an instrument that can ignite itself, and yet they insist upon speech. The edge of devotion in trust is a match head.

In the final utterances of the book, the poet’s coursing agency comes to a head. In the last poem: “Wrong star I chose / To sail under alone” an insistence to navigate one’s life on one’s own terms, folding in all the re-scripted intelligences and creative counsel, delivers the reader into an aura of intimate buzzing. For we ultimately choose “Which question / Needs answer.”

Sara Ellen Fowler is a writer and artist living in Los Angeles, CA. Her work has appeared in The Offing, X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly, Hysteria, and Office Hours Los Angeles. She holds a BFA in Sculpture from Art Center College of Design and is an MFA candidate in Poetry at UC Riverside.

This post may contain affiliate links.