Matt Mitchell’s hotly-anticipated debut The Neon Hollywood Cowboy emerges as one of Big Lucks’ swansongs. It is a book of poems that plays with our expectations of masculinity, defying classic tropes and imbuing references across genres, eras, and feelings. Mitchell’s lilting, conversational confessionals have power where one may try to impose shame, and bravely make a name for himself as the forerunner of contemporary intersex poetry. Including references to Stevie Nicks, John Wayne, Red Dead Redemption 2, Mitski, Ohio, Coca-Cola, the most triumphant presence in the text emerges as Mitchell himself.

Matt Mitchell’s hotly-anticipated debut The Neon Hollywood Cowboy emerges as one of Big Lucks’ swansongs. It is a book of poems that plays with our expectations of masculinity, defying classic tropes and imbuing references across genres, eras, and feelings. Mitchell’s lilting, conversational confessionals have power where one may try to impose shame, and bravely make a name for himself as the forerunner of contemporary intersex poetry. Including references to Stevie Nicks, John Wayne, Red Dead Redemption 2, Mitski, Ohio, Coca-Cola, the most triumphant presence in the text emerges as Mitchell himself.

Mitchell and I spoke over a FaceTime call, delighting in a conversation of pop culture, book design, intersex poets, music, and of course, cowboys.

Gabrielle Grace Hogan: Why cowboys? Is there a deeper meaning for the cowboy as a trope in this book, or do you just like Westerns?

Matt Mitchell: Yes to both. I like Westerns – I mean, I grew up watching Westerns with my dad, and my grandfather was a really big fan of John Wayne. But cowboys, in regards to the text, are not so Western-heavy, more so the idea of masculinity and who can be a cowboy, who gets to claim themselves as such. I want to break down the idea that a cowboy is just a cis white guy who duels people outside saloons.

Yeah, because the cowboy is kind of the image of American masculinity.

Yes. And in an interview with Maudlin House I already did for the book, I talked about how in the Wild West there were transgender cowboys and there were Black cowboys and cowgirls, and probably a lot of intersex cowboys just given the ratio – 1 in every 200 people are born intersex, or with sex chromosome disorders, and most of them don’t know it. So with that ratio, I would assume, there were quite a few intersex cowboys running around.

There was a Twitter thread a couple weeks ago highlighting trans cowboys and Black cowboys, and I was really stoked because people were tagging me in it and I was like “yeah, this rocks.” I’m glad people see this thread and think “gotta tag Matt.”

Glad this is your poetic legacy.

If that’s all I ever have, that’s fine with me.

I’ve been lucky enough to read a lot of these poems before TNHC had a book deal, and it’s so exciting to see them finally coagulating into a collection. How has sitting with this book affected you as a writer and person? How has finishing the book done the same?

I’m now much more comfortable talking about myself and talking about who I am with people. I’ve gotten asked a lot of questions – someone’s doing a review of the book and they texted me to ask me questions about some of the more personal parts of the book – and for the first time, really ever, I’m really comfortable talking about it. Even though it’s kind of really still terrifying because I’m putting out a very personal body of work and a lot of people are going to be reading it, and I have the feeling that a lot of the people who are reading it do not share the same identity. I think whenever you’re putting out art about yourself, it’s scary thinking about the people who aren’t you reading it, and how they’ll feel about it. But, in terms of finishing it, I’ve changed in that I’m glad that it’s done, because it gives me space to work on my next book and make that book better than this one. It’s good to know what benchmark you’re at and what you’ve already done, and how you can surpass that in the future.

For sure! And it may be my own negligence, but there’s not a lot – at least there’s not a lot of “loud” – intersex poets, or well-known intersex poetry. It’s not that you’re the first or the only, but I know for me you’re probably the most significant intersex poet that someone could name. How does it feel being the forerunner of that, being the person people think of when they think of intersex poetry? Is it rewarding, does it make you nervous, both?

Yeah, I think it’s both. I like it but I’m also scared to death about it. Because, as with any marginalized identity, it’s a gigantic spectrum. My place in the spectrum is not the same as other intersex people that I know, but that doesn’t make me or them less valid. We’re just co-existing in this weird, wonky habitat together.

It’s scary, because I don’t want to be a spokesperson for anything. Knowing that I might be one of the first people to publish a whole book of poetry about this is rewarding, but also puts me in a weird place because I know for a fact I’m definitely not the first intersex person to publish a book of poetry. It’s such a weird identity to have because. If you’re not born into hermaphroditism, the only way you can really tell is through blood tests and DNA procedures, and that’s a very privileged place to come from because you have to go to specialists, and specialists cost money. With this sort of accolade, it also comes with trying to figure out how to dismantle my own privilege. This book comes from a very underrepresented place in poetry, but it also comes from a source of privilege that is adjacent to the disparity in healthcare that a lot of artists, especially artists of color and trans artists, are fighting every day. It’s a very complicated path, and I still don’t have the right answer for it. I don’t know how to completely break it down, but I’m hoping that, as I continue writing poetry about this thing that’s going on with me, that I can also learn how to better advocate for people that are worse off than I am.

You don’t want to be a token, and you don’t want to assume your experience is the only intersex experience, and you don’t want others to assume that either.

Right.

What has been your experience working with Big Lucks?

Bittersweet. I love it, it’s a dream press to be a part of, and that is the sweet part. The bitter part is that I’m most likely the last book that Big Lucks will put out for a very long time.

Big Lucks was very formative in my introduction to poetry. A bright spot is that, even though Big Lucks is going to take a step back from publishing books, it’s not the press I love, it’s the publisher, and I’m privileged enough to be very good friends with my editor, Mark Cugini. Being friends with Mark means that’s a forever thing, and we don’t have to be doing book stuff to be friends.

I think Big Lucks has already cemented their importance in the literary community and to be an extension of that is a gift. If I could go back to last March and get a chance to pick any publisher I want, I would not change it. I would go Big Lucks again. I’m going with Big Lucks all the way.

Mark is one of the most amazing people, and so I can only imagine them as an editor is equally as beautiful and wonderful as having them as a friend.

It’s great because Mark has read a lot of poetry, so when Mark compliments your work, it’s so validating because it’s stacking up against a decade’s worth of stuff. Which is nice. I just love them.

You heavily utilize pop culture and Americana in your work. What’s the pull towards that?

I counted and there’s over 50 references in this book. It’s funny, because I get asked that question quite a lot, and I’m becoming known as the “pop culture reference poet,” and that’s cool! I just don’t want my work to be remembered as leaning too heavy on things that came long before I was alive. I don’t think I write about them as much as I write next to them – you can use pop culture to better emphasize the moment you’re talking about. I come from a household where we’ve never been much “go outside and do it” kind of people. We are inside homebodies. I grew up around a TV, I grew up listening to music, and I grew up with the radio on all the time, movies at night. It was a bonding thing. In a way, this book is a lot about me – the whole thing is basically straight up about me – but when I’m using these references, they’re all references about things my parents exposed me to. It’s my way of trying to connect with them, because sometimes they don’t understand poetry, but when they see something they recognize, it goes a long way.

Every reference is something that I care deeply about, but it’s also an olive branch extended to people who don’t immediately gel with poetic work. References, when you don’t lean on them, can really bring in an audience you wouldn’t have had. I can tell someone that my whole life twice a week is about needles, and they’re like, “what does that mean, that makes no sense, I don’t get that.” But then you try to make the connection to something else: In the 70s, all the music that Neil Young was making was about his bandmate who died from a heroin overdose and his songs became all about the negative effects that come from needles. So here’s my transition: It’s this crazy thing that has to do with needles that happened to me, and sort of consumed me, and now it’s all that I can write about. That’s the connection. And you go from there, and if they can gel with that, then you’ve got them.

Of all the people mentioned in this book, who would you most want to have a copy of TNHC? Who would you least?

Least, probably Keith Richards, because he’d probably tear the pages out and try to roll a joint with them. He would just desecrate the book—not intentionally, but he’d just be looking for rolling papers, and have to resort to my book.

The person I would love to get my book in front of would be John Wayne because he would hate my existence. He would hate me, he would hate what I wrote about him in the book, he would be so pissed – I’d get blacklisted, I’d never get a shot in Hollywood. He’d read it and throw in the trash and be like “ban that guy from every club!”

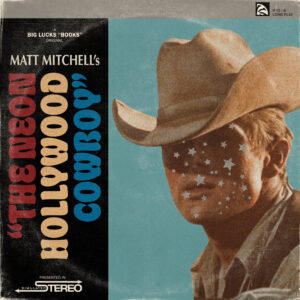

I know cover design is really important to you. You make them often in your spare time. I’d love for you to talk about the process of designing and landing on this book cover.

That’s a great question. No one has asked me yet about the cover, which I find shocking because it’s the best book cover ever made.

It’s a dope cover, and if anyone knows anything about you, they know that the fact that you have a cover that is the cover is quite a commitment.

It is quite a commitment. I counted it up and I made 37 different iterations of this cover. And when I say iterations, I mean different color schemes, designs, textures, fonts. I think aside from the poems inside, the cover is the most essential part of the book. People always use the very exhausted saying, “you can’t judge a book by its cover,” but I have never bought a book with an ugly cover. It doesn’t even have to be a cover that you would look at and say, “I would have a cover like this for my book,” because there are so many covers that I can appreciate that I would never consider putting my poems beneath. I think that if there’s a really beautiful cover done, that is really appealing to the eye, it shows to me how much effort and how much thoughtfulness and how much care was put into the project. If you just slap a really horribly put together cover on a book that very well may have incredible stuff inside, it’s a disservice to the author.

The way that we got to the final iteration is that I basically combined all of the things that I had considered doing separately into one. The first idea was to make it a movie poster, but then I landed on what should’ve been the first idea the whole time, which was making it look like a record. The whole book is filled with music, and I love records, I collect them, and I’m especially a big fan of worn-out records. I like to spend an hour in the clearance bin at record stores with all of the aged, scratched, worn-down records, because I like the idea of something that has been really loved.

In terms of the picture itself, I wanted James Dean on the cover from almost the very beginning. I’ve got him on there from his movie Giant which came out after he died, and I put glitter stars on his face – I wanted something a little feminine on the front, and I thought the font was retro and lovely and spoke to the era that the book is so desperately reaching for. And I have a very fond romance for American iconography, so I wanted the color scheme to be traditional American flag colors.

What question do you want me to ask you in this interview? What question have you been wanting to answer?

I would like someone to ask me whether Red Dead Redemption 2 has any influence on the creation of this book.

Does Red Dead Redemption 2 have any influence on the creation of this book?

Yes. I played Red Dead Redemption, the first game, right around when it came out. I was about 12, 13, and I loved that game more than life itself. I don’t know why. I had no affinity back then for cowboys. I got the Play Station 4 in January 2020 and I finally got to play Red Dead Redemption 2. By that time, I’d gotten into a very, very deep rut trying to write this book, and did not understand where it wanted to go. I played RDR2 and, the entire time I was playing that game, did not write a single poem. When I finished the game I wrote probably 10-15 poems, finishing the book. The first poem in the book, which is titled “The Birth of the Neon Hollywood Cowboy,” was originally titled “Ode to Red Dead Redemption 2.” I had felt such a strong connection to the idea of using your given masculinity as an act of redemption, but not necessarily in the sense of “I’ve killed a lot of people as an outlaw and I need to be better,” but more as a sense of me personally using my platform as a man to try and break it down. I saw someone on Twitter a couple of days ago say they ordered my book because they have not seen very many deconstructions of masculinity in tender ways, and I felt very full of joy. I was filled aplenty with gratitude knowing that people picked up on that, and I owe a lot of that to RDR2 as a game. Arthur Morgan, the protagonist, is a flawed man, but probably one of the most non-toxic men in video games. I would trust him with so many things – he is a good person, I should’ve put him in my acknowledgements.

Where can people find you and why should they want to?

You can find me on Twitter @matt_mitchell48. And you can see me in The Neon Hollywood Cowboy, coming to a theatre near you April 14, 2021.

The Neon Hollywood Cowboy

by Matt Mitchell

Big Lucks

April 14, 2021

Gabrielle Grace Hogan is a poet from St. Louis, MO. Currently, she lives in Austin, TX as she pursues her MFA from the University of Texas at Austin as part of the New Writers Project. She is the Poetry Editor of Bat City Review, Co-Editor of the online anthology You Flower / You Feast, and author of the chapbook Soft Obliteration available from Ghost City Press. She is on Twitter @gabrielleghogan.

This post may contain affiliate links.