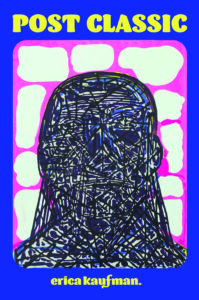

[Roof Books; 2020]

“welcome to this work of a certain age:” this is the last line of erica kaufman’s epic, Post Classic.

I love that this introduction comes at the end and the way it urges me to pause and reflect back through the poems that I’ve just read. What journey have we been on and where have we landed? Which story brings me to this ending, to this beginning?

*

When kaufman’s speaker asks, “dear epic why can’t / ghosts talk about disgust and desire reborn,” she is addressing one of the oldest forms of poetry. Found in Ancient Asian and European civilizations, epic is a long narrative poem grand in scope and story. Far-reaching journeys and battles accompany supernatural beings and events. The narrative often follows a hero whose actions come to stand for the morals and beliefs of the culture. When kaufman’s speaker asks, “dear epic why can’t / ghosts talk about disgust and desire / reborn,” we enter an encounter with epic that begins in medias res with heroines and poetic displacements and wanderings and visions and critique about our 21st Century.

Suppose, kaufman writes, and brings genre to the fore. Suppose, she states, transporting epic through time to a contemporary now. Suppose, she suggests, signaling the transformations often associated with literary epic in which this becomes that, beings become others, landscapes shift suddenly, timelines extend across ages, and supernatural gods and goddesses like guides appear, retreat, appear again when you most and least need them.

*

kaufman is writing an epic trilogy, and Post Classic is a companion to her previous epic, Instant Classic (Roof Books 2013), and both are companions to her book-to-come. The texts think about epic as genre — as a literary form, category, container — and as field, possibility, invitation, and archive. In her first book, Instant Classic, she writes, “I believe there are some archives that are ecstatic.” I’m drawn as much to the sound of the words as to the idea: ecstatic archive. The etymology of ecstatic is that which is mystically absorbed, in entrancement and astonishment, and it is also that which is unstable, inclined to depart from, displace, a removal from the proper place. The image I see is a more established archive — textual, gathered in its materiality and placed-ness — that is beside itself.

We can hear an ecstatic archive at work in Post Classic. In one poem, the speakerclaims, “I like / to avoid fostering generic stability” or what if I don’t play by the rules? What if I take the tropes I want and invent others? What if the heroine’s voice merge and separate between speaker and writer? In another poem, the speaker claims, “harbor me eccentric i can’t wait / to walk all these grounds fuck all / these canons their song a lone.” kaufman’s lines challenge how literary canons can create inclusions and exclusions. In the place of the solitary “lone” canon is an “eccentric” circling, wandering, walking “all these grounds” away from a single center to create more space for poetics, archives, and oneself.

Ecstatic archives suggest to me literary histories that are gloriously, expansively displaced from their proper or traditional place, made to be beside themselves, suddenly more and multiple and other than they were. The idea of ecstatic archives can help us analyze how contemporary writers engage previous epics and their histories. At the same time, in the more and multiple, there are diverse voices, stories previously untold or silenced, and genre done in experimental poetic ways. An ecstatic archive makes space for complexity and imagination and, in the epic spirit, stories for future readers searching for a history of the present.

Post Classic is ecstatically beside epic.

We can say making and unmaking.

A return. Reborn.

*

Throughout Post Classic, epic tropes and allusions are present. There are mentions of journey, guide, hero, oceans and ships, battles, voice, story, history, oration, and direct addresses to epic itself. Epic interlocutors include Milton, Homer, Gilgamesh, Waldman, Notley, Robertson.

While kaufman’s text finds inspiration in a literary epic tradition, at the same time, it questions certain inheritances. Post Classic also looks closely at representations of masculinity, war, conquest, the act and figure of memorialization that most often commemorates nation building. And the text says, yes, lets! include all that epic gathers into it as it moves through history, criticism, canons, and feminist rewritings to the Post Classic contemporary.

kaufman’s poem “Proem” is an extended overture to epic. A proem, as a form, is a poem that provides an overview of the story to come. kaufman’s “Proem,” in a similar, delightful achronology as the welcome that closes the book, is found in the middle of her collection. It asks epic, asks us, to “look back”:

dear epic let’s look back

to canvas return gesture

as primal part of the earliest

genre of parlor games balderdash

garden of continuous charade

outside of the history of history

we don’t engage don’t flaunt

homecoming obscure rhetoric

border progression repurpose family

prayer sing to me of use tell

me a story of practice air conditioning

gutter fancy sing to me again because

there is no new error no prophecy

of dancing violation let’s begin in request

kaufman’s poetics may be described as one of proximity. Words placed side by side highlight the individual word and posit relations with the words around it. When reading “homecoming obscure rhetoric // border progression repurpose family,” I suspend expectations about syntax and consider how these words modify one another in multiple directions at once. In a sense, I pause in the lines. I sense how one word implicates another and another. For example, I read, “homecoming obscure” and “obscure rhetoric” and “rhetoric border” and “homecoming obscure rhetoric border” as language iterations that are pushing to make evident systemic relationships that power silences and to insist on sensemaking as a creative, necessary act.

Less paratactic lines work in similar ways as phrases and lines relate associatively: “as primal part of the earliest / genre of parlor games balderdash / garden of continuous charade / outside of the history of history.” In some instances, line breaks punctuate a stop. In others, they create a quick turn, moving me, moving language with immediacy. kaufman’s poetics enact the transformations I see in ecstatic archives. Words, phrases, and lines that are made to be beside themselves, alongside, all suddenly more and multiple and other than they were before.

*

The collection’s opening poem, “an (invocation)” borrows The Odyssey’s first words — “sing to me.” Traditionally a call from poet speaker to muse, we can imagine an invocation as an appeal extending beyond a speaking self to more ethereal realms, requesting assistance and inspiration from an otherworldly other. Sing to me, tell the story through me. I, poet inspired, will speak the story of our time, place, people.

Sing to me an ecstatic archive into existence.

The opening stanzas of “an (in)vocation” read:

sing to me emotionless exercise

tweet the essence of how i hear you

say “circumferential” “birthplace”

“infrastructure” “subway” dogma

say i hear you verbatim so sing

to me of intermissions and water

mark my name a logo pregnant

with handshakes sing to me of

material troops of fortified islands

harbor me eccentric i can’t wait

to walk all these grounds fuck

all these canons their song a lone

stork an act of trying to use

ballet as frame to dramatize

certain collisions open wary

monumental battery sing to me

of mandates . . .

The poem calls us into the text. In its own way, it declares, “Welcome to this work of a certain age,” which is a U.S. 2016 (now ongoing) political crisis. Alongside the recurring “sing to me,” other language conjures epic including words associated with journeys (“water,” “islands”) and battles (“material troops,” “fortified islands,” “collisions,” “monumental battery”) and the genre itself (“All these canons their song”). Also present — at times distinct, at times overlapping — are the languages of nation and the presidential campaign. “Tweet the essence” names the former president’s mode of political communication and commonly heard claims about “birthplace,” “Infrastructure,” “handshakes,” and “mandates.”

kaufman’s invocation is marked by parentheses: “an (in)vocation.” The title cues us to a poet speaker who is in vocation. In one sense, the parenthetical emphasis can speak to the elevated sense of vocation as a calling or being called upon to do good work. In another sense, it signals a poet at work, as in the dailiness of going to work and navigating institutions and power relations. Entwined throughout the book are the dictions of work, education, pedagogy, sexuality, gender, dailiness, grind of working within hierarchical systems of all sorts, and ongoing visionary work of creating a livable world.

I hear work in the opening line. A sense of yearning associated with a poetic invocation is interrupted as soon as “sing to me” encounters “emotionless exercise.” The latter phrase speaks to work’s dailiness, routine, and also of learning practices. I pause. Emotionless does not mean not intimate for in Post Classic I hear, Sing to me of a time and place where discourse and body and desire and systems and oppressive politics and work and labors of love and otherwise coincide in a word, line, stanza of language unfolding into epic. Let me tell you this story, she says.

*

In kaufman’s collection, there is an epigraph from poet Alice Notley, author of the feminist epic, The Descent of Alette. Speaking about epic and revisions of the genre, Notley states, “ . . . Perhaps this time she wouldn’t call herself Helen . . . Perhaps someone might discover that original mind inside herself right now, in these times. Anyone might.” The statement is a provocation that plays with the origin-making work of epic by positing an original mind, a woman who is not named as or after Helen of Troy. Instead, a first mind. Before any fall from Eden, any abduction of story or person.

In Post Classic, we meet a mercurial poet speaker who is an “original mind” and more. The line between writer and poet speaker blurs. There is commentary about the narrating voice and how it operates in the text. Lines from different poems give a sense of the dynamic:

“but again i’m in her voice, the original”

“know my protagonist she’s becoming / idiomatic as only character afraid / to bring emotion back capsized”

“my hero dissolves // all men build fences instead of hauntings / she draws on emotion & other vocabularies”

She meets the moment with what she deems is called for, moving between modes of address, and between confrontation and clandestine maneuvers. She spars and is sly, clever, disruptive, withdrawn. Throughout the book, she retreats and then reappears. There is some refusal, critique. Some wit, some lament and provocation. An excerpt from the poem “Post Classic” (many poems take the book title or riff on it: ie, “Post Pedagogy” and “Postscript”) reads:

in the beginning i introduce myself.

in the beginning i’m hoarse not fallen.

shame takes positive costume adorned

in glass limbs. in the beginning i hear

language lift the curtain, shift present tense

to back stage. in the beginning we all become

something. no question of heroism. no

imaginary tables to set. outcome comes

real because it’s heartless to only touch

in and promise. like the surprise of a required

dressing room mandate to introduce

myself by identity market i’m not one.

who makes excuses for any kind of omen.

or hears tales on front lawn. if you heed me

i will devour “him” supplant any graces with

statutes of matriarchy. her simple contours.

troublesome branches. sing to me . . .

In the poem and in Post Classic as a whole, gender is a genre to be scrutinized, with a poet-speaker voicing the knots: “like the surprise of a required /dressing room mandate to introduce / myself by identity market i’m not one.” In many ways, kaufman enters a conversation with other literary critics and poets who challenge a dominantly male epic tradition. However, kaufman pressures both gender and genre with questions about categories and how they impose identity. Post Classic adds to the conversation by unsettling the two terms, sometimes by putting gender/genre into uncomfortable close association, and sometimes by pointing to places that refuse to fit. Or, as the speaker claims in another poem: “the body is not / a text not hard not tempted / deviant common flood binary”

*

I return to the end of the book and kaufman’s closing note titled, “re-translation note.” It reads:

suppose when i use the word “epic” it becomes a narrative that’s contem-

orary.suppose there is no garden to begin with, to fall from, to weed. instead a

place where disobedience is desired and desirable, alternative fact consti-

tutes sin in this space.suppose a post classic where “post” indicates a relation to information, and “classic” signifies the familiar yet outstanding, time-tested recipient

of one’s gaze.welcome to this work of a certain age.

*

kaufman states, “Given that I’d begun the book several years earlier, and given the results of the 2016 presidential election, I wanted to think about the potential of re-translation as another kind of world-making.” She shares how the initial Post Classic manuscript contained poems built (in a more procedural, found language sense) from language collected from far-ranging literary sources — classical epic to lesbian pulp fiction, and poetic tracts to critical theory. She shares that this is a familiar way of writing, of making poems. However, when she returned to her already-done manuscript in the context of the 2016 Presidential Campaign and its escalating “racist/sexist/homophobic/ableist rhetoric,” she was compelled to revise it, to re-translate it in a way that brings closer or makes more explicit connections between language and self, between epic and current events. “The epic,” she states, “needed to come out of me and my own subject position.”

*

Welcome to this review of a certain age. I begin this piece on index cards in the slow-hectic drone of early quarantine. Carrying the stack from one room to another, the composition unrooted yet emphatically in time. I exercise, zoom, post, disinfect, teach, volunteer, dog walk, donate, meditate, walk, sit, study. My way into writing is on small, demarcated spaces. How un-epic, cards that let me see the beginning and end at once. How casual, how composing. They pile in a book on a table in an extending timeline day after day.

Ah the punctum of the index card, its pointedness. One might say punctual, my return to writing about epic and the idea of a genre making and unmaking itself. From this nexus, this knot, I am theorizing what I call epic encounters and how contemporary texts engage the tropes and themes of literary epic in multiple, diverse, amplifying and defying ways. I ask, what does epic make possible for contemporary women writers? And I read works that point me in a direction – toward a telling that shapes differently, imagines in new ways, and meets a present time.

In “Theory, A City,” Lisa Robertson writes, “Theory is the space made by returning, in order to have a position from which to view the world. The space is collective and solitary: mutual.” I’m now also carrying around this quote as a way to understand something about epic as return, about making and unmaking, about space and point of view.

Replace “theory” with “epic”: “Epic is the space made by returning, in order to have a position from which to view the world. The space is collective and solitary: mutual.” Instead of a point we already know, how can we think about epic as a space of dynamic movement transformed with each return? As a poetics through which to write worldly visions. Epic and worlding and epic as a way to reimagine a world — a poetics of “world-making,” a word that kaufman uses in her collection.

Maybe I should start here.

Andrea Quaid’s work focuses on poetry and poetics, pedagogy, and feminist studies. She is co-editor of Acts + Encounters (eohippus labs), a collection of works about experimental writing and community, and Urgent Possibilities, Writings on Feminist Poetics and Emergent Pedagogies (eohippus labs). She is series co-founder and editor of Palgrave Studies in Contemporary Women’s Writing. Her work appears in albeit, American Book Review, BOMBlog, Entropy, Feminist Spaces Journal, Jacket2, Lana Turner, LIT, Los Angeles Review of Books, Manifold and Syllabus. With Harold Abramowitz, she curates RAD! Residencies at the Poetic Research Bureau. She teaches in the Bard College Language & Thinking Program and Institute for Writing and Thinking. She also teaches in the Critical Studies Department at California Institute of the Arts. She directs Humanities in the City, public programs focused on education equity and the transformational power of interdisciplinary humanities study in classrooms and communities.

This post may contain affiliate links.