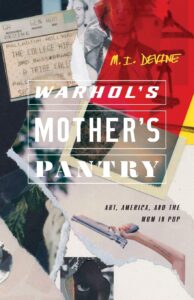

[Ohio State Press; 2020]

By the title, Warhol’s Mother’s Pantry: Art, America, and the Mom in Pop, M. I. Devine leads us to believe that the book will retrace the art of Warhol through the eyes of his mother and uncover the little-known genius of Julia Warhola in the shadow of her son’s glory. We could surmise from Warhol’s artmaking style that the simulacra by Warhol of Warhola may significantly remove us from the woman herself. I admit that I was hoping to learn more of the woman’s biography and discover the son’s mythos by inhabiting the mother’s pantry, as an artist myself and once Gallery Assistant at the Whitney Museum of American Art for the exhibition Andy Warhol — From A to B and Back Again. Meanwhile, Devine dissolves this mystery because the pantry could be any pantry — it even seems to invoke Devine’s kitchen in the quarantine of 2020, so the pantry may not be at all as it seems, though it is a piece of any artist’s private life nonetheless. What is the draw to Warhol? Devine appeals to the pop icon as central to transform an American mythos just like many art critics proclaimed the major retrospective apropos of “bringing Andy Warhol into the Digital Age.” Curator Donna De Salvo argues essentially, “Perhaps more than any artist before or since, Andy Warhol understood America’s defining twin desires for innovation and conformity, public visibility and absolute privacy.” Moreover, Devine is interested in investigating American pop aesthetics within our largely mediated times, not to trace a familial history, so the book only offers hints of a throughline of Warhol and Warhola.

In fact, the totality of Devine’s work is steeped in an American mythos to reclaim the synergy of pop songs, poetry, and photography for our own contemporary imagination. The most curious secret is unlocked in the book’s acknowledgements: if you, like me, did not know, M. I. Devine is a pop artist and lyricist too. Thus, Devine’s stake in pop art becomes self-evident. We owe the book’s conception to a soundtrack, called “WARHOLA!” The record project Warhola by Famous Letter Writer is, self-described, “a high energy live show — synth-driven, part spoken word, obscure sampling, all CBGB spectacle — to capture the poetry of pop.”Linked to the indie pop record project, Devine claims that the soundtrack originated first: “I wrote a soundtrack for this book before I wrote the book itself.” Likewise, the book is invested in recasting critical essays of pop ephemera with lyric elements and poetic notations.

I hope you will put in some beats, tune into the “you ain’t crazy” melody of Warhola and roll back in time. A little reminiscing will go a long way to pardon the nostalgia of the book and heal from any triggering of unhappy memory. Do not fret: this is not a book about motherhood. This is not a book that urges you to call your mother and change your name back to your birth name. There may be some religiosity to it; whether or not you are religious, the book invokes the spirituality of pop. That said, the human personhood of Julia Warhola may be lost to nostalgia because she evokes an idealized persona for Devine; indeed, as Devine becomes enraptured in an attempt to make a hymnal of pop songs, the overlays of religiosity may prompt a reader to approach Julia Warhola as the Virgin Mary of the story: “Her first child dead in her arms / A little girl / Julia / Warhola / Rather die with your child / Pieta.” If this book attempts to literally reclaim and center the woman in pop, it fails. Truly, this book has little to do with Warhol, let alone Julia Warhola. The book is also not interested in entertaining the politics of visibility, as it does not investigate the particularity of Warhol’s origin story beyond “the immigrant’s son.” Devine’s lines may be emotively charged but are cut short: “In a village in Slovakia / Mom and pop.” Why does the pop poet-critic choose to give so little? Perhaps there are untold stories of lost archives. As Devine describes the soundtrack “WARHOLA,” “It’s a record about pop. And memory. And the things that get erased. We learn to sing by singing along — with others. Through others.” Perhaps, because the music album is invested in a contemporary audience, the book concerns itself broadly with the shape of identity, culture, and memory.

The question remains: Who is the mother of pop? We may continue to ask that question after studying the book. Does the mother even have to be a woman? I hope we could further queer what Devine offers as a foundation of pop music and the lyric essay. Julia Warhola is not the mother of pop. Rather, Devine makes the case that the container or the form is the mother of pop: it is “deliberately crafted to impose order.” Just as the container is often the way poets speak of what the sonnet does to shape and hold memory, Devine presents the soup can as the container of Julia Warhola, especially in Andy Warhol’s memory and work.

Furthermore, Devine explores the pantry or room as a container through photograph-inspired vignettes. Is it possible to conflate the sonnet with a selfie? Devine ponders the narcissistic accusations of the selfie gaze, and he seems to conclude that a portrait of self is self-invested and selfish. Needless to say, the vignette may be a valuable and inclusive container to hold personal memory through grief. By extension, the contemporary mode of the selfie locates the self in a room, so a selfie is a container of the memory of the self. The heart of the work is truly found in a full section devoted to Philip Larkin, in which Devine paints a more popular American portrait of the poet through a return to Larkin’s coming-of-age and his photography of himself in front of a mirror, which Devine claims as perhaps one of the first mirror selfies. Curiously, Devine imagined readers may not recall Larkin was ever a teenager, titling one section “Philip Larkin Was a Teenager.” Clearly, Larkin was once a teenager. I have assigned Larkin’s “This Be The Verse” for English Composition with community college students, and my students routinely raise concerns of youthful rebellion through the discussion of the poem’s themes. The poem is a stark portrayal of parents’ shortcomings even as it commands a collective affect. As Larkin closes the poem, he advises, “Get out as early as you can, / And don’t have any kids yourself.” Ironically, Larkin becomes the father of a new generation. His mirror selfie was before its time. I, for one, am eager to share his photography alongside the poem with students. Just this semester, in fact, I opened a new project at Queens College to investigate the selfie, and my students would have been intrigued by his mirror selfie. In collaboration with the Godwin-Ternbach Museum, my students explored the digital exhibition HUMAN/Nature: Portraits from the Permanent Collection in order to approach shared questions of “how we portray ourselves and others in selfies and photographs taken on mobile phones and posted on social media.”

I admit I am a selfie artist, and I’ve felt the accusations of narcissism too. While just a jab, the cynicism can cut deeply when another perspective reveals the sensitivity of queer visibility and self-expression. For me, a trip to a museum is similarly self-indulgent: a kind of spiritual practice, in which I revisit the legacies of countless artists and find new ways to look at myself and the world. My first socially distanced adventure this holiday season was a trip to the MoMA. Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans were home. I admit I may have taken a selfie in front of the soup cans because Devine’s work and my students’ projects were still on my mind. I also found a treasure trove of photo-booth self-portraits of ordinary people that looked to be dated earlier than the famous one of Warhol himself represented in the Godwin-Ternbach Museum’s digital exhibition. As I turned about the museum, I could not help my gaze falling upon my company in the gallery: a dear stranger was taking a still life of a paper-cup with Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans as backdrop. The paper-cup had a Campbell’s soup label on it and definitely looked to be formerly well-nourished with some mushroom soup. I did not even need to take a moment to wonder why. We are obviously fascinated by reproductions: all simulacra of the real. However, as the sociologist Jean Baudrillard reveals, the chain of infinite progression is infectious; overtaken by a capitalistic marketing system, reproduction is endless, until meaning becomes perhaps null and void. I have seen similar enactments, while maintaining galleries myself as a Gallery Assistant. Warhol enthusiasts will bend to wild stunts like upturning a pant leg to reveal the socks that just happen to match Warhol’s art.

No doubt, the attention to the gaze, through the grandeur of Warhol, prompted me to reminisce of the “good ole days” in the galleries of the Whitney — to think how gallery spaces have changed with the pandemic and social distancing. In my time, the exhibition Andy Warhol — From A to B and Back Again was the most spectacular show at the museum (although my favorite by far was David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night). As a Gallery Assistant, I stood watch, beside many of Warhol’s works, as the freight elevator unloaded more and more visitors. They were not allowed to come with selfie sticks, but many still snuck them into the galleries with backpacks and strollers. My strange mindset now wonders that a selfie stick may be the perfect way to keep six-feet distance from another random visitor in the gallery, only they’d have to utilize them in reverse to protect the art. Devine’s book states the obvious — we all can’t help that Warhol’s work is very photogenic, inviting a selfie at every turn in a mammoth exhibition.

Then my own memory met Devine’s own in a personal moment of the book’s musings. He recollects, “I never told you about the boxes. How as a child, they could not keep me from them.” As a Gallery Assistant, I naturally shrug when the very act of shame — how dare you touch the art in a museum! — comprises the nonfiction turn of the book. Devine reveals his younger self may just have crawled on Warhol’s Brillo Box (Soap Pads) to discover what they were: “Mother, sister, inside the museum. Lose me in a Warhol kind of wing. Bright. So new. Wondered if they were empty. Brillo: red, white, and blue. You’d look at all the sides to see. Cubes.” I doubt his childhood self actually had a rapturous moment with Cubism.

I will say, in offering, to imagine an exchange, in my own endearment to his childhood self, that Warhol’s “Flowers” are all the same. Devine seems to beg the question to Julia Warhola, in search of flowers, “The flowers all say the same thing,” and I do affirm this without a doubt. I sat in a small exhibition room of Warhol’s flowers day after day to find it was a selfie trap. I remember once a visitor, making small talk with me, encouraged me to pull out my phone and take a selfie in uniform, just so I could show loved ones someday that I worked for a renowned museum to maintain a historic retrospective exhibition of the life work of a genius. Meanwhile, one of my team whispered to me, “the sky has eyes.” It was code for: there are cameras at every angle, taping footage of anyone who dares to turn in an anti-normative way and touch the art. I think I found a better way to reminisce. I dare to write honestly that I never figured out exactly why the curator cleverly chose to juxtapose the pink and yellow cow wallpaper with the colorful flowers. Truly, it made for a very claustrophobic overstimulating room that may never pass the inspection of visitor services post-quarantine. If all the flowers say the same thing, the flowers hung in a grid upon the wallpaper say a different thing: take a selfie with me, with all of me!

I do know for a fact that Warhol’s Brillo Box (Soap Pads) are always stacked differently in every exhibition, and the many flower paintings may never be in the same room again. They were acquired for the retrospective from countless collections. I wander from the point. Needless to say, the art of curation, like remix, hearkens back to the most interesting aspects of Devine’s book: his devotion to turns in form.

Devine

relishes in repetition, rehearsal, and the remnants, refashioning each major

piece of the book’s criticism

with creative postscript. The creative postscripts are titled “After

. . .” as opposed to the critical

notes titled “On . . .” in the fashion of a

Montaignian essay. “After Warhola”

is the longest and most intriguing. Fragments

of a whole flow over six pages. Together they create a kind of ekphrastic

ballad about Warhol painting in memory of his mother and the speaker’s bearing witness to the relic. In the second

rehearsal, Devine moves beyond Warhol into the abstract like a ritual: “do

this in memory.” As Devine

overturns the practice, his thought reflects Baudrillard’s theory of simulacra and the endless chain of

signification: “it never stops like how a painting of one thing is

actually another thing.” Jacques Derrida’s “archive fever” takes hold, as the pop poet clings to the hope of an

archaic mother: “a painting is not a painting is a mother.”

Re-mothering a modern self, the voice invokes

religious myth, while what is recast is evocative and sacrilegious — beside “Byzantine icons,”

we see “His soup cans,”

and the lyric declares, “Eat

this in memory of me.” As the

ballad turns further into a pop hymn with rhyme, the mother evolves into the

body of a Christ-figure: “A colostomy bag / Insides on

her outsides . . . Not one of her bones will be broken . . .” The final section proclaims the witness of feminine

suffering: “They pierced her side with a spear, bringing a sudden

/ flow.” The stanza break marks a

curious turn back to the soup cans: not a flow of blood after all, but “Cream

of mushroom.” Why mushroom? Maybe

a distinct flavor and a fungus. Three times the speaker ritualizes the call-out

culture of canceling with a parenthetical line strikethrough: “(I John saw these things and heard them.)” It’s

hard to say, but the mis-reference prompts two Biblical remembrances: Peter

denied Jesus three times, but John stood witness to Revelation. Is John the

speaker of the ekphrastic ballad and therefore witness to the art? If so, the

speaker may be canceling his own voice in order to proclaim that the modern

self cannot possibly be first-hand witness to an artist’s breath of inspiration. We are too far removed. Such

knowledge may be lost, even to an archive. A selfie with sacred artworks,

ancient or modern, may ritualize the affect of knowing. In the act, we must be

cautious that we do not perpetuate the myth of totality.

Therefore, detached from Warhol and Warhola, the creative pieces serve Devine’s authorial motive to capture and re-construct another story: the relationship of poetry to pop culture, photography, and song. Through creative criticism with lyric citations, Devine intermixes an evolving poetic refrain, so a long section extends the exploration of the pop lyric refrain in the fashion of a poem’s turn. He also explores the relationship of poetry to collage through the image of scissors and paper cuts. That section may inspire poets, at a loss for words, who are drifting into collage, erasure, and assemblage through the pandemic. There’s a brief mention of Jean-Michel Basquiat and homage to Michael Stewart, which may only begin to challenge the classic American ethos.

There is a significant and apparent gap: perhaps over-invested in hailing pop’s rightful place within the “high” art of criticism, the book obsesses over many Western canonical voices, including James Joyce and John Donne, to foreground an “American” tradition and does not champion legendary black voices in jazz and blues that shaped American pop. The book, not a project bent to historicize, is evidently steeped in the biases of our current moment; it even pokes fun at Trump’s historical lack of taste in decorating the Trump Tower. I find it disheartening as well that the book invokes John Donne to label him “a spiritual schizophrenic” and “bulimic.” By forwarding obvious personal commentary about religion, the voice risks not only further stigma of mental illness but also sacrifices care in rewriting the literary histories of human people who walked the face of this very same earth. On a metaphysical level, I am afraid that the voice endeavors to raise itself to the heights of meta-narrative; meanwhile, the judgment to deem cultural rituals of our times and centuries ago to be a kind of iconography is just one limited human point of view. This subjective stance fails, losing sight of human frailty, because it is so enraptured to challenge human expression of self and the divine.

Curiously, another soundtrack from the album offers essential commentary, aligned with the ethos of the book. In the official music video of “All in My Head,” the lips of ordinary people at home trace pop history in the USA through pop icons and magazine reading. The primary voice cries, “Oh Siri, can you tell me? Is it all in my head?” The haunting voice claims to be authoritative and representative, ghosting the screen. At a central point in the video, we see the body of the voice standing beneath a dart board, as if crowned with a golden halo. The video grows accusatory in tone, as it ends with a moral lesson that audiences have been “obsessed” with their “own vanishing.” Supposedly, “there will always be someone who wants you whole.” I wonder who that could be. The voice’s body has vanished into a void black frame. It seems to be no coincidence that an orchid wilts beside him, creating the eerie picture of a vanitas. The song cannot escape its own nihilist critique of narcissism. Vomiting the self does not raise a ghostly self to a superior standing of divinity. Self-love uplifts a human because it grounds the self on earth in order to endure the elements of human frailty and earthly struggle. In our current moment of crisis, globally and nationally, it is challenging to parse the critique. While greater media literacy is required to understand how mediated communications tend to dictate our projections of self, I do not find it constructive to further invalidate voices that find means to overcome the oppression of silence through individual memory-telling. The legacy of human value and freedom will carry on through history, upheld by artists and writers. Meanwhile, we each have blindspots to bear upon. That is why we read and write.

Thus, the book, so titled after Warhol, leaves me adrift. In a slightly eerie way, this book was my first reading of hybrid creative criticism as a means to comment on our current moment and theorize about the pandemic’s effects, aside from social media commentary, photo-journalism, and zine projects. There’s certainly a sense of nostalgia and unrest, longing for a return to some kind of stability, even as the book glosses over the privilege of #StayHome. It’s hard to ignore. Devine writes: “His mother’s pantry, her insides on her outsides; the messy fact of interior matters, that interiors matter: pop traces our fragile social bonds, and we’re valuing that now, perhaps more than ever.” At first, I hoped he was speaking of the pandemic of 1918, when he writes, “a new dark age each in our cell,” but the lines about streaming pop in the room like “What are these rooms where we stream?” triggered quite obviously the felt-sense of our here and now; these were fresh edits, transformed conclusions in quarantine.

To rekindle joy, I’d like to return to the room of Warhol’s portraits and imagine this book is as much about Warhol’s picture of the mothering self as it is about our present crisis — the book is indeed writ large about remothering the room that contains the self. Likewise, I dare to believe and hope that we will return to museum galleries in mass numbers. The question is when. The question is what we will hold dear to gaze upon. Will another retrospective of Warhol’s work of such grand scale happen ever again? Even then, no one wanted to be stuck up against a stranger’s backpack, pinned between visitors, craning their neck for a view to read the name that matched each portrait. I admit that I coveted the hour I was allotted to sit on shift; I reveled so much in the Gallery Assistant’s chair that even a visitor thought I was part of the art at least once. To my chagrin, I may have failed to focus attentively on the portrait of Julia Warhola in the room, though I never took a selfie in my less-than-fashionable uniform on the floor.

Kara Laurene Pernicano earned a MA in Literary and Cultural Studies with a Certificate in Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies from the University of Cincinnati. Currently, she is a MFA Candidate in Creative Writing and Literary Translation at Queens College, CUNY and an Adjunct Lecturer in English for CUNY. Artist and writer, she celebrates intersectional feminism, queer love, art and healing. Her creative work explores hybrid image-text practices.

This post may contain affiliate links.