The following is from the latest issue of the Full Stop Quarterly. You can purchase the issue here or subscribe at our Patreon page.

The Dawn of an Age

Clear and calm, Tuesday, June 24, 1947 seemed like the perfect day to look for the C-46 transport plane that had gone down near Mount Rainier a little over a year before. Kenneth Arnold thought he might be the man to find it, and with good reason. An experienced pilot with over nine thousand flight miles under his belt, Arnold often subsidized his salary with just such search and rescue missions. Indeed, the C-46 had a reward of $5,000, an equivalent of about $57,000 today. But even more than money, his numerous missions scouring ocean and land for wreckage earned Arnold a keen eye, able to identify even the smallest of remnants from thousands of feet in the air.

Taking off from Chehalis, Washington at 2pm, Arnold banked west along the jagged ridges of the Cascade Mountain Range in which a downed plane could easily disappear. Seeing nothing, he trimmed east. Then, he glimpsed something out the window, due north. But it wasn’t the aluminum of a fuselage glinting in the snow. Instead, what he reportedly saw in the crystal-clear sky gave the world a new reason to crane their necks towards the heavens and wonder exactly what lay in the stars.

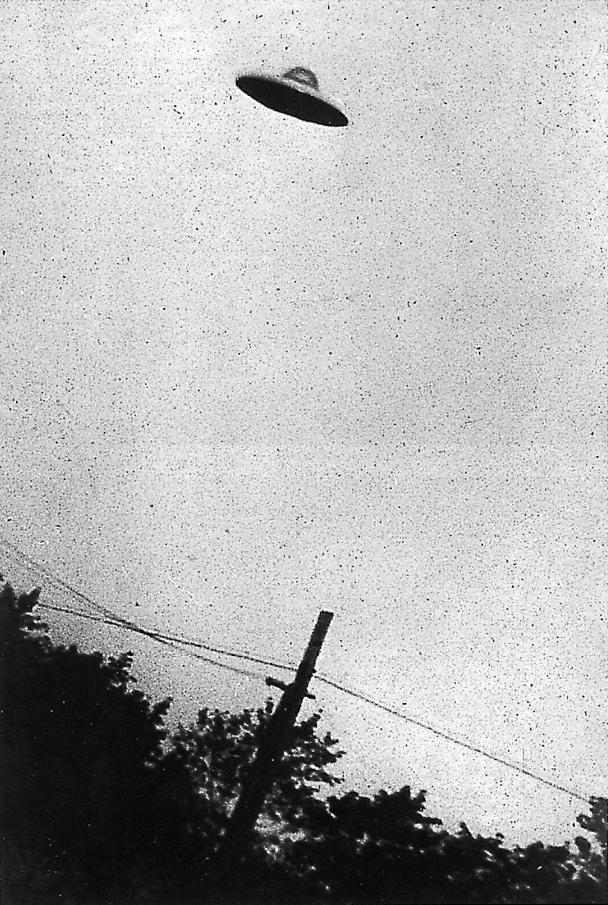

Nine discs flying in a V formation at 9,500 feet cast a perfect shadow against Mount Rainier’s snowy slopes. Arnold rolled down his window for a better view at the aircrafts that by his own description moved like saucers being skipped across water. The sky roared around him as he kept them in sight until they disappeared past Mount Adams at a speed Arnold reckoned at about a thousand miles per hour.

Making a b-line to the airfield in Yakima, he called his report into newswires and government agencies alike, feeling it was nothing short of his patriotic duty to do so. The government dismissed his claim outright, as did many journalists. But the AP wireman who took down his story ran it under a headline that would ignite the age’s imagination: “Supersonic Flying Saucers Sighted by Idaho Pilot.”

So dawned the age of flying saucers. All of a sudden, otherworldly crafts were seen zooming everywhere through the blue vault of day and dancing in the darkness of night. With its open skies and penchant for wild imaginings, America seized upon this phenomenon en masse. By 1948, more than eight hundred sightings had been reported and an unprecedented 90 percent of American adults had heard of flying saucers according to one Gallup Poll.

America’s panoply of local newspapers was more than eager to run these extraordinary stories that started appearing on front pages across the country.

In July 1947, for instance, the Norfolk Journal and Guide reported “Mrs. Luicille Robinson of 1107 Church Street” watched a silvery and rapidly moving object for two or three minutes before it disappeared, “leaving a light glare in the sky.” Almost simultaneously, The Daily Boston Globe reported an even more incredible account in which two hundred beachgoers sighted a flying saucer hovering so low over Braves Field in Boston that “it was in danger of being shattered by a high fly ball.” The owner of the beach’s snack shop went on the record saying, “I don’t know what it was, and I’m not a crackpot. But we saw something and it looked like a saucer.” Later that summer, the Baton Rouge Advocate ran news of a similar mass sighting when “a crowd of 200 observed a disc at Hauser Lake, Idaho on the Fourth of July. A group of 60 picnickers saw them at Twin Falls, Idaho. And in Portland, Ore., so many residents witnessed them that same day the police department sent out an all-cars broadcast.”

Beneath the irradiance of these otherworldly disks quickly grew a thriving community of flying saucer enthusiasts. Skeptics portrayed these believers as poor, uneducated, rural whites whose flights of fancy were the inevitable outcome of growing Cold War anxieties coupled with a fear of the fast-advancing technological age.

In reality, the majority of those who made up the burgeoning UFO community did not fit this particular bill. Instead, the extraterrestrial movement’s founders as well as its most ardent followers were self-educated middle-class suburbanites. Many of them were even respected retired military officers. Moreover, it was not irrational fear that early adherents ascribed to extraterrestrials, but measured concern.

The nuclear arms race hit its stride early in 1949 as the US regularly tested ever more powerful bombs in the Pacific Ocean and the Soviets set their first atomic weapons off in undisclosed locations somewhere in Siberia. Meanwhile, American scientists attached a camera to a WWII requisitioned Nazi V2 rocket and blasted it a hundred miles high. The images it took were the first to picture earth from space, a vantage point from which humans could see how very small and how very fragile we really are. Another V2 rocket was refitted to accommodate the world’s first astronauts: fruit flies whose ascent past the atmosphere opened the door to the idea of manned spaceflight. Humans were simultaneously advancing their nuclear and space capabilities. This dangerous combination, according to the UFO movement, was what drew these extraterrestrials to earth, though not with belligerent intent.

Instead, benevolent concern attracted them. Evidence, they claimed, could be found in the high frequency of sightings above nuclear power plants and Air Force bases. In any case, they had yet to obliterate us despite our clear technological disadvantage. And, it was widely assumed, their capacity for space travel indicated peaceful civilizations capable of creating the sustainable conditions necessary for the development of such technologies. According to early adherents, these were traits to be admired and emulated. As such, the UFO movement was adamantly opposed to nuclear weapons, America’s emergent military industrial complex, the rampant materialism of the 1950s, and increased environmental degradation of a globalizing economy. In many respects, these early UFO enthusiasts outpaced several of the progressive social movements of the 1960s and ‘70s.

Nowhere was this attitude of reasoned optimism reflected more than in the Aerial Phenomena Research Organization (APRO), the first civilian UFO investigation group. Founded in 1952 by husband and wife, Jim and Coral Lorenzen, APRO stressed a scientific approach to the research of UFOs. It soon attracted distinguished board members including Dr. James McDonald, a senior physicist at the Institute for Atmospheric Physics and Berkley Engineering Professor, James Harder. But more significant than the contributions of its high-profile board members were the reports of UFO sightings recorded and collected by its dedicated members, which were then disseminated nationwide in its mimeographed newsletter.

Well-written, proofread to perfection, and elegantly typeset, the APRO Bulletin was not a publication of crackpots. Indeed, well aware of the reputation of many associated with the UFO movement, APRO was careful to distance itself from more fringe elements. The January 1953 issue, for instance, bore the headline “Beware of Hoaxers” and went on to decry those with a “vivid imagination, whether that person is looking for publicity, suffering delusions of grandeur, or just love to have other people think he knows something they don’t.”

Another dispatch from that summer with the headline “Saucermen with Buckets” recounted the tall tale told by miners in Bush Creek, California of tiny extraterrestrials who’d shown up to their digging in “saucer-shaped craft and scooping buckets of water from the nearby creek.” The article continues, “We can easily and correctly predict that goodly number of the curious will be on hand on that supposedly fatal day and that the local general store will have field day in the sale of pop and other refreshments. However, we seriously doubt that the little men will put in their scheduled appearance.”

Adjacent to these strategically placed gainsaying columns ran major sighting events reported by those that APRO deemed credible. One of the more remarkable examples occurred in 1953 as the Korean War drew to a close. During a prisoner exchange, the Bulletin reported, “something else of great importance happened, for an object which was silvery white in color raced above Pan Mun Jom at supersonic speed. It was seen from the ground and tracked by radar.” Four American reconnaissance fliers confirmed the ground sighting. “Looks as though they’re pretty interested in the Korean situation,” the article concludes, “maybe they could give-some pointers.”

The remainder of the APRO Bulletin’s ten mimeographed pages was largely filled by the organization’s overall raison d’etre: member UFO sightings. Amalgamated under the regular section simply entitled “Sightings,” these accounts were so numerous and so packed with mundane detail that they almost had to be true.

For instance, the September 1954 issue alone ran one report from Bay Shore, Long Island, where “many reliable people,” including a distinguished Royal Air Force Pilot, saw a cigar shaped object with a black tail; another from Fort Lauderdale where several jet fighter pilots saw “a gleaming white ball” hovering approximately four thousand feet below their position before disappearing into the east horizon at a speed that far exceeded their own of four hundred miles per hour; and yet another from Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania where a local radio station received calls for seven straight days about mysterious objects in the sky, many of which congregated around an Air Force Radar Station. More than a dozen similar such sightings appeared in each APRO quarterly edition.

By the mid-1950s, APRO boasted thousands of members. In effect, Jim and Corel Lorenzen had harnessed the wonder inspired by these mysterious lights and channeled them into an organized movement of enthusiasts whose belief in the existence of extraterrestrials was both optimistic and unshakable, two adjectives that any given member of the 1950s middle class might use to describe themselves.

But as the Cold War spun out of control and the post-WWII economic boom began to fade, the middle class found its apogee and subsequently began its initial descent. Founded by and composed of middle-class members, the UFO movement followed this downward arc. This darker turn might be said to have begun with Betty and Barney Hill, a husband and wife from New Hampshire whose 1961 encounter with aliens would help to define a new era of the UFO movement.

Lift Off

The Hills were not the first to claim to have encountered an alien face to face. That honor went to George Adamski, a hamburger flipper and founder of a new age religion called The Order of Royal Tibet. His 1953 encounter with a peaceful extraterrestrial who resembled in dress and appearance an alpine skier ended with a well-intentioned if dire warning about the development of nuclear weapons, in keeping with the time.

But by 1961 when the Hills ran into extraterrestrials, the world did not look like it did in Adamski’s day. In April of that year, the CIA trained squad of Cuban defectors, Brigade 2506, landed on the beaches of Havana. President Kennedy had promised Castro’s regime would crumble at the first sign of opposition. Categorically, they did not and would be vanguards of regime change were soundly defeated. Soon thereafter, the Soviets planted a suite of ballistic missiles on Cuba’s shores, not ninety miles off the Florida Coast, marking the moment when the Cold War came closest to nuclear annihilation.

It was not hard to read apocalypse in the stars and the sky had become a place not for wonder, but where one looked, furtively, hastily, and anxiously for the incoming fire of hell. So it was perhaps with burnt orange glasses rather than rose ones that Betty and Barney squinted at a bright light in the sky that seemed to be following them down the highway as they returned from vacation at Niagara Falls.

A more wholesome pair than the Hills could not have been invented. First, their names, Betty and Barney, seemed to scream a kind of quant respectability. Then, there were their occupations. Barney worked for the Post Office and Betty had spent her professional life as a devoted social worker. More remarkable still, at a time when race relations in America largely meant Jim Crow style segregation, Barney was African-American and Betty was European-American. They were, in other words, upstanding, and so their story seemed all the more tragic, and all the more believable.

After miles of trying to outrun the light that grew closer by the minute, Barney finally relented, and pulled over to the side of the road. What he thought he saw could not be real, or so he reasoned. Retrieving a pair of birding binoculars, he tried to get a clearer view of whatever phenomenon he seemed to be witnessing. The light came into focus, tilted, then descended. A row of windows, a craft, then a handful of figures started to move toward them in black uniforms and black caps.

And suddenly, as the couple later reported, they were back in their car, down the road, no worse for wear, but with a few hours of their lives missing that neither could account for.

In a course of events that now seems formulaic, the Hills began to recall what actually happened to them. It started with Betty’s nightmares that seemed to glimpse at memories of an operating room and dark figures standing above her. After months of these night terrors, both submitted themselves to regression hypnosis. While in this altered state, they separately recalled the abduction in chilling detail. It was gruesome, the stuff of nightmares, and fodder for a new wave of sci-fi features. It also set the tone for the next four decades of UFO culture.

In the coming years, an increasing number of individuals reported similar experiences. They were taken at night, experimented on by faceless creatures, then returned psychologically scarred but with few physical manifestations to corroborate their otherwise vivid accounts. Most significantly, they experienced what came to be called “missing time,” a period that an individual could not account for, but knew had elapsed. But foregrounded by the Vietnam War and the Peace Movement, the Civil Rights Movement and the white nationalist reaction, the burgeoning Feminist movement and the patriarchal backlash, this troubling trend didn’t make many waves.

Eventually, the turmoil of the 1960s subsided when, as Hunter S. Thompson wrote, “the wave finally broke, and rolled back.” In its wake was the landscape of a nation that refused to rise to the moment, to adapt, to embrace its better angels. The middle class swept the likes of Nixon, Ford, and Reagan into the White House, and in so doing, arguably decimated itself as their supposed leaders transformed America into a kleptocracy. Their fortunes, particularly in relation to the upper classes, began to decline precipitously. Once again, the UFO movement reflected this increasingly turbulent reality. This time, it took a hard right.

It began appropriately in the heartlands with a symbol more American than the flag itself: beef.

Conspiracy and Collapse

Between 1969 and 1979, the American economy entered into a period known as “stagflation,” in which inflation averaged 6.4 percent and unemployment remained at about 6.3 percent. At the same time, global food shortages in 1970 coupled with anti-communist humanitarian foreign aide efforts meant that more grain was being sent overseas, causing a shortage in the United States. That in turn catapulted the price of food, and particularly meat, by 30 percent. The middle class, in other words, were getting the squeeze.

In 1972, women began picketing supermarkets in protest of these unpayable prices. In response, then President Nixon tried to quell the would-be neo-Whiskey Rebellion by freezing prices for the first time ever in America’s peacetime history. This attempt to stabilize the economy put an inadvertent vice grip on cattle ranchers who were already seeing their profits plummet as feed prices went up and demand went down. In turn, ranchers collectively decided to withhold their cattle stock from slaughter, resulting in a 19.2 percent decrease in beef production. Rather than bolster their cause, this boycott nearly ruined the entire cattle industry in what cattlemen would later deem “the Wreck.”

Things were looking apocalyptic in cow country. And then, the situation went from bad to worse. In the fall of 1973, ranchers in Kansas and Nebraska began seeing bizarre lights in the night sky. But what they found in the morning was more disturbing still: the carcasses of cattle with eyes, ears, sex organs, and rectums removed with the precision of a surgeon. Others had been exsanguinated, down to the last drop.

At first, ranchers suspected what had become their ultimate enemy: the US Government. More specifically they placed blame on the Central Intelligence Agency, a shadowy spy agency that seemed to embody all that was wrong with Cold War America. Rumors of CIA helicopters deployed for black ops training and gruesome medical experiments spread along the barbed wire fences until it had been repeated so many times it became as good as true.

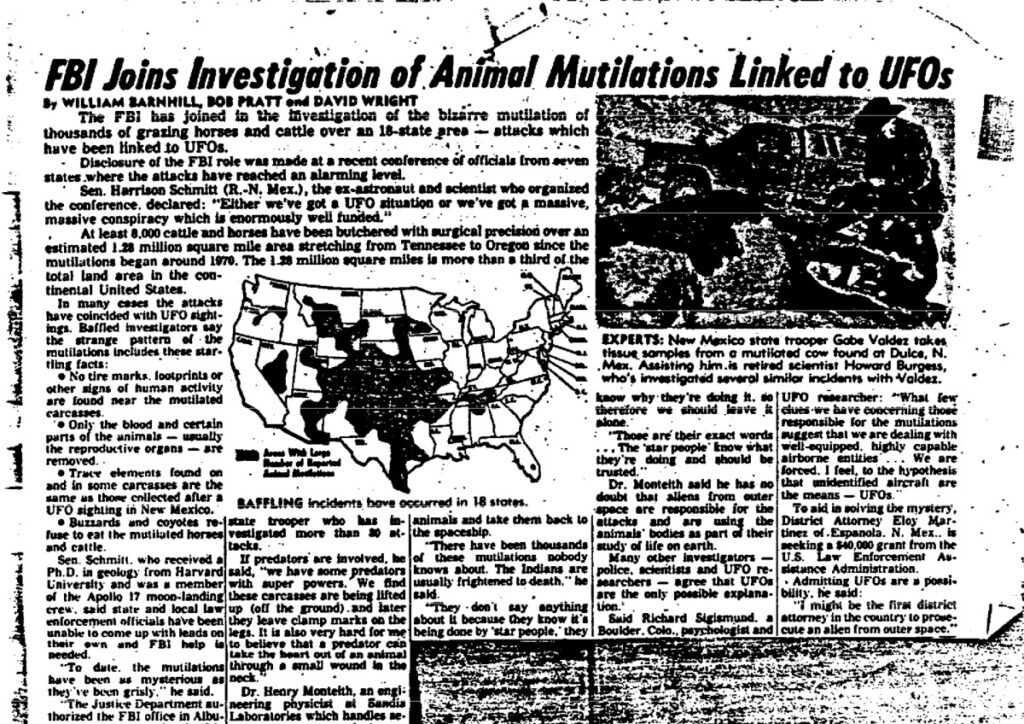

But as the cattle mutilations grew more numerous and widespread, and as the lights that accompanied them seemed to grow brighter, a different type of rumor began to spread. Many started to suspect aliens to be behind these uncanny events. Soon, tales of alien cattle mutilations had become so prevalent that national newspapers started covering the story.

“They did this in plain sight,” one rancher told the Los Angeles Times in September 1975. “Anybody looking over her at night would have seen them, their lights or something.” He was speaking of the recently discovered cow cadaver with its rectum cut out. All that remained, the reporter wrote, was a “smooth circle where the blade had been.”

But, as the town’s sheriff commented, “Hell, this is the least I seen done to one of em’ so far.”

The Austin American Statesman likewise reported on a rash of cattle mutilations in 1975, though with a more matter of fact tone than the LA Times’ sense of drama. “A 750-pound Charolais bull was found in Anderson County Sunday in a pine grove. The bull’s sex organs, ears, and tongue were missing. The hide on one shoulder had been peeled back. All the blood had been drained from the carcass in an unexplained manner.” If this were not enough, the report continued, “a large cow was found Monday near Tyler on the Ashby Ranch. The cow’s vulva and tongue were missing. The cow was seven months pregnant. No blood was found around the carcass. Its fetus had been removed.”

By that winter, eleven states had reports of cattle mutilations and even the New York Times sent a stringer to assess the situation. Like everyone else, she was befuddled. Despite the problem’s pervasiveness, “as yet, all investigators including some Federal officials in Minneapolis, have been able to turn up any clues indicating human involvement in the killings.” Coyotes and foxes were floated as culprits. But as one rural sheriff said, “there’s no question in my mind that two legged creatures are responsible for the mutilations.” In the face of such ambiguity, the Times included the possibility of UFOs. Quoting the agent in charge of the Colorado Bureau of Investigation inquiry into these mutilations, the article concluded ambiguously, “I’m not ready for the UFO theory. Maybe I’m narrow minded.”

This theory got a shot of growth hormone in 1980 when KMGH-TV out of Denver, Colorado broadcast A Strange Harvest, a documentary by local film-maker Linda Moulton Howe about the wave of unexplained cattle mutilations that had plagued the Middle West for the better part of a decade without explanation.

At the time of the film’s release, Howe was a respected regional documentarian who focused on environmental issues, corporate pollution, and government culpability. Her diminutive demeanor and good looks coupled with her sharp wit knocked her subjects off guard and got them to say more than they would have otherwise. But when it came to reporting on cattle mutilation, her trademark objectivism and cool-headed journalistic instincts seemed to abandon her. However, her storytelling prowess remained in full force.

The result was a compelling film proposing that cattle mutilation as the work of aliens and more sensationally still, that the US Government was both aware of and complicit in these otherworldly dissections. At a time and in a place where paranoia was at an all-time high and trust in government at an all-time low, Howe’s film struck a chord with profound resonance.

Like the flotsam and jetsam of America’s plains caught in a dust devil on a hot August morning, tales of alien encounters and stories of a corrupt government were swept up into a swirling tower until they became indistinguishable in a single moving mass.

Behold, a Pale Horse

Since the establishment of the League of Nations after World War I, xenophobic nationalists had been warning of a cabalistic consortium of global elites working to bring about an authoritarian one-world government. Umbrellaed beneath the catchall phrase, The New World Order, this conspiracy evolved and morphed with world events through WWII and into the Cold War. By the mid-1980s, as Perestroika came into full effect and the Cold War began thaw, this conspiratorial metanarrative alleged that Illuminati backed Jewish bankers sought to impose global communism in the form of an atheistic, bureaucratic collectivist world government.

Predictably, this particular kind of thinking both inspired and attracted members of the growing militia movement comprised largely of economically displaced white men whose lack of education now barred them from the middle class as well-paying but low skill jobs had mostly disappeared from the American landscape. To them, the New World Order was a simple to understand, yet complex enough to be believable explanation as to why their lives looked the way they did. It was, to them in any case, more compelling than intangible economic abstractions and the geopolitical posturing of two world powers in countries they could neither pronounce nor identify on a map. And, unlike the actual reality of the late Cold War, they could protect themselves from the eventualities the New World Order espoused by amassing guns, stockpiling food, and building bunkers. With such Hieronymus Bosch-esque visions of the future, it was only a matter of time before this particularly muddy river intersected with the increasingly apocalyptic UFO movement.

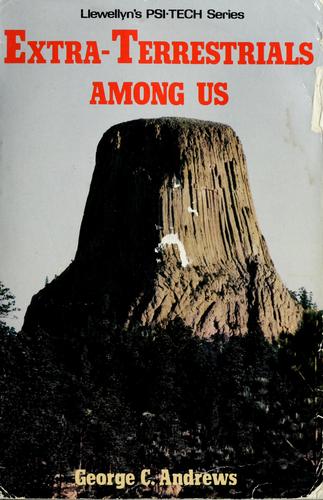

Then, in 1986 George C. Andrews, a self-styled poet, drug enthusiast, and crystal skull collector, did just this in his book, The Extraterrestrials Among Us. An exhaustive volume of over three hundred pages, Andrews’ was the first widely read work to fuse the New World Order ideas with government sanctioned extraterrestrial experiments. According to Andrews, the elites of the world were colluding with extraterrestrials to control world events. The CIA, which Andrews called a “government within the government” was the main means of imposing their will on the masses. The very idea of this synthesis ran down the spine of UFO enthusiasts and militia members with the thrilling jolt of a lover’s hand. Eventually, to a large degree, these two groups became one.

Conspiracies of alien-backed CIA operations, mind control implants, and mass abductions ran rampant within far right for the remainder of the Cold War period. Militia leaders including Montana Militia spokesman Bob Fletcher and influential author Milton William Cooper, as well as Oklahoma City bombers Terry Nichols and Timothy McVeigh subscribed to the idea that aliens and the US Government were working hand in glove to bring about an autocratic one-world government. It was the ultimate betrayal and the perfect apocalypse, the definitive close to one era and the dark beginning to another.

The End Is the Beginning

What began in 1947 as a largely hopeful movement defined by wonder, openness, and concern for mankind, plunged into the paranoia-fueled mire that skeptics had always assumed the UFO movement to be.

It is perhaps too easy of a metaphor. But the invisible hand of the market may well have arrived in the form of a spacecraft during the Cold War. As events beyond the control of the everyman raged around the globe, the middle class witnessed its own steady decline, the reasons for which were obscure and the solution to which was not forthcoming. While environmental disaster and the collapse of the stock market left many searching for work in the Great Depression, the Stagflation of the 1970s could not be so well defined. There was neither a date nor a dust cloud one could point to and say, this, here, is why our lives are difficult. Similarly, there was no solution, no Works Progress Administration, no war between good and evil that could offer a tangible way out.

Instead, both the problems and solutions were always so far beyond the grasp of most that they might as well have resided in the stars. No wonder those already looking there saw in them the end. And no wonder for those whose world was ending looked to what were once the heavens for answers. As we approach a new era of paranoia and a new epoch of conspiracy, it is hard not to look back and see just exactly where everything went wrong.

Lorissa Rinehart writes about war, peace, and art. Her work has recently appeared in Lapham’s Quarterly, Perfect Strangers, and Narratively, among other publications. Her website is lorissarinehart.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.