[World Editions; 2020]

Tr. from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman

I first read La perra by Colombian writer Pilar Quintana during a trip to Bogotá in summer 2019. First published in 2017, and winner of the Biblioteca de Narrativa Prize, the novel had been a publishing success in Colombia and that summer, I struggled to find a copy in any of the capital’s bookshops. I only got hold of the book after a friend passed me her own copy and in a few hours, I read this short novel, which on the surface tells the unassuming story of a woman named Damaris who lives in a small village on Colombia’s Pacific coast, and explores the fallout after she adopts the female dog alluded to in the title.

Despite its brevity, La perra masterfully constructs a fully realized world that not only explores the inner consciousness of the protagonist and the region she inhabits but touches upon major themes such as motherhood and infertility, the relationship between humans and animals, race, and the forces of nature. The story lingered with me for a long time after I read the original Spanish version, and now, thanks to a seamless translation by Lisa Dillman, which has been shortlisted for the National Book Awards, English-language readers have the chance to read one of the most thought-provoking and celebrated recent works of Colombian literature.

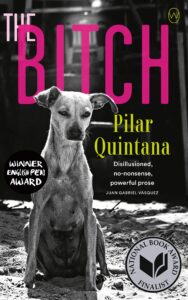

The cover of the English-language version and the translation of the novel’s title, The Bitch — which simultaneously references the female dog adopted by Damaris, as well as the common slur used against women in both English and Spanish — starkly illustrate one of the novel’s central themes, that of maternity and the social weight of motherhood. The title appears in hot pink font above a grey image of a female dog, her breasts and nipples clearly visible. This sets the tone for the story contained within, which begins with the death of a female dog who leaves behind a litter of six-day-old puppies, only one of whom is female, who Damaris decides on a whim to adopt. Taking the puppy home, Damaris begins to take care of her as if she were a child: “The tiny dog fit in her hands, smelled of milk, and made Damaris long desperately to hold her tight and cry”. As she goes about her chores in the small shack she shares with her husband “on a jungle bluff” overlooking the sea, the novel begins to establish Damaris’ backstory. Raised by her aunt and uncle in the run-down coastal town after her mother left to work as a live-in maid in the major port city of Buenaventura before being killed by a stray bullet, Damaris had married young and following convention, tried to start a family with her husband Rogelio. Now, after many years of failing to become pregnant, and “about to turn forty, the age women dry up, as she’d once heard Tío Eliécer say”, Damaris adopts the young pup and names her Chirli, the name she had chosen for the daughter she never had.

The parallels between the childless Damaris and the orphaned puppy are thus quickly established from the outset of the novel. Yet, despite her initially pampering the dog — “During the daytime, Damaris carried the little dog around inside her brassiere, between her big soft breasts, to keep her nice and warm” — the novel slowly demonstrates the unravelling of their relationship and how the puppy does not become the idealized, surrogate child that Damaris longs for. After the dog repeatedly runs away, Damaris begins to resent and “feel annoyed by the dog’s presence, her smell, her scratching and shaking off”. This rejection is compounded by jealousy when the dog herself becomes pregnant: “Damaris felt as if she’d been punched in the gut: she couldn’t breathe”.

Chirli, however, turns out “to be a horrible mother. On the second night she ate one of her puppies and in the days that followed abandoned the remaining three so she could go lie in the sun by the pool”. The Bitch therefore not only implicitly critiques the social pressure and pain of frustrated motherhood — describing how people would ask Damaris “Where are the babies”, depicting the impact of infertility on her relationship with Rogelio, and “the stabbing pain she got in her soul every time she saw a pregnant woman” — but seeks to desacralize the experience of motherhood and the social roles of care ascribed to women. Chirli’s abandonment of her pups, and of Damaris, is paralleled by the (involuntary) abandonment of Damaris by her own mother as well as Damaris’ own increasingly violent behavior towards Chirli and her eventual decision to give her to a neighbor in town, leading to the moment when Chirli’s “face turned to Damaris, staring in distress as though she’d been left at the slaughterhouse”. This is embedded in a broader context in which the novel’s relationships of care, and the relations between humans and animals, are marked by violence and abandonment. Prefiguring the denouement of the book — Quintana defines La perra as the story of a crime — this is a town where dogs are poisoned or turn up dead, where litters of unwanted puppies and kittens are “thrown into the cove to be swept away by the tides”, and where people themselves reach mysterious ends:

Señor Gene’s death was very mysterious. No one ever found out what happened to him or how he’d ended up in the sea. By that time he was completely paralyzed by his illness and could move only his fingers. Most people believed he’d committed suicide by throwing himself from his wheelchair over the bluff . . . There was another group who thought Señora Rosa had pushed him.

Importantly, the novel’s graphic description of Señor Gene’s body, which washed up after twenty-one days at sea — “his fingers and toes eaten away by animals, his eye sockets empty, his belly swollen” — echoes another traumatic event from Damaris’ childhood when Nicolasito, the son of one of the families who vacationed in the town, is also swept out to sea and whose body is only recovered thirty-four days later: “The skin had decomposed from the salt and sun, been beaten down to the bone by fish in some places, and, according to those who were there the body reeked”. This moreover points to one of the other major themes of the novel — the representation of nature as a brutal and deadly force. Building on a long Colombian literary tradition that explores the country’s frontiers and natural spaces, The Bitch has clear echoes of foundational novels such as José Eustasio Rivera’s The Vortex (1924) and more recently Tomás González’s In the Beginning Was the Sea (1983), in which characters, typically those from Colombia’s urban interior, travel to its peripheral regions and are overwhelmed by the terrifying forces of nature.

To an extent, the novel reinforces this brutal representation of Colombia’s jungles, coasts, and natural world, and it is significant that Quintana chose to set the story on the Pacific coast. The Spanish edition emphasizes this location over the foregrounding of gender and motherhood on the English-language cover. The Spanish edition cover depicts a black sand beach, empty except for two weather-beaten boats, beneath a dark grey sky. For a reader in Colombia, this is identifiably the Pacific, an area of immense natural resources and one of the most biodiverse regions of the planet but also one that has been historically represented, as Aurora Figueroa Vergara states, as a “wild, isolated” territory in the Colombian national imaginary. Thus, alongside the deadly Pacific Ocean, the novel represents the difficulties and dangers of this part of Colombia. Damaris is represented as in a constant battle to keep the forces of nature at bay, which constantly invade the house as she tries to keep it clean. She is described as hating the jungle bluff where she lives and into which the dogs repeatedly escape — “There were too many cliffs and bluffs with slime-covered rocks . . . snakes that were venomous and others that could swallow a deer, bloodsucking bats that bled animals dry”. The description of the natural world in the novel significantly has echoes of The Vortex’s elaborate modernist personification, where the jungle appears as an exotic, powerful, and sensual force that also overwhelms the reader in its terrifying otherness. In The Bitch, the jungle begins to invade Damaris’ state of mind: “it was the jungle that had stolen into the shack and was coiling around her, covering her in slime . . . until she herself turned into the jungle”.

However, Quintana nuances this historical representation of nature as a wild and “savage” space, which has often gone hand-in-hand with attempts to “civilize” the area and extract its immense natural resources. As Figueroa Vergara also notes, this representation erases “a long history of colonisation and oppression that has taken place in this territory”, which is predominantly inhabited by Afro-Colombians who have suffered the long-term effects of poverty, structural racism, and the legacy of racialized colonial violence. Responding to this history, Quintana chooses not to place narrative control into the hands of an outsider who arrives in one of Colombia’s peripheral regions but instead foregrounds characters like Damaris, and other inhabitants of the town, who form part of Colombia’s Afro-descendent population. Thus, the interrelations of race and class are hinted at throughout the narrative. The novel makes clear the situation of precarity in which Damaris and Rogelio live, scraping by through fishing and housekeeping, and compares their shack on the jungle bluff to nearby property “where white people from the city had big beautiful weekend homes with gardens, paved walkways, and swimming pools”. Indeed, Nicolasito is the son of one of those well-off families, who after his death, never return to the house and eventually stop paying the caretakers, like Damaris, who continue to maintain it.

In this representation of the race and class dynamics of the Pacific, the novel subtly problematizes the discourses of development and tourism, and the poverty and violence, that continue to define the region. In this way, it also goes beyond well-worn representations of violence in Colombian culture. The country’s armed conflict, for example, while clearly forming a backdrop to the narrative — Damaris’ absent father is described as “a soldier doing his military service in the region” — is subsumed within the novel’s innovative concentration on issues of structural violence and silenced subjects, such as infertility, motherhood, and the nature of love and care in marginalized communities. Reflecting the increasingly complex and multifaceted depictions of the Pacific in Colombian cultural production, The Bitch refuses to either celebrate the natural beauty of the coast or reinforce a folkloric or idealized image of its inhabitants. Instead, it expertly weaves its politics into a psychologically complex story that centers a character, and her desires, frustrations, and emotions, who is not commonly represented in either Colombian or international literature.

Cherilyn Elston is a lecturer in Latin American Cultural Studies at the University of Reading, UK. She is the author of Women’s Writing in Colombia – An Alternative History (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016) and the translator of Jorge Consiglio, Southerly (Charco Press, 2017). She is the managing editor of the online literary translation journal, Palabras Errantes: http://www.palabraserrantes.com/.

This post may contain affiliate links.