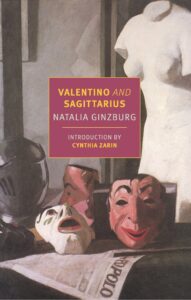

[New York Review Books Classics; 2020]

Tr. from the Italian by Avril Bardoni

Natalia Ginzburg is punishing in her fiction. Her stories, including her two novellas, Valentino (1951) and Sagittarius (1957), recently reissued under one volume by New York Review Books Classics, consider every tragedy that can befall the domestic sphere: doomed marriages, familial betrayals, the precarity of wealth, death. Ginzburg lavishes in teaching her characters a lesson. Her novellas are containers for the cruelest of ironies, and the results are two morality tales, pushed nearly to the limits of realism. And yet, however absurd the developments in each novella, there is still something oddly realistic, and devastating, to the finished product.

In Valentino, the titular character is working towards a medical degree, and is supported hand and foot by his family. But his family is poor, making plenty of sacrifices to further Valentino’s education. Clara, Valentino’s older sister, especially has it hard, with three children, one who is sickly, and a dead-end job typing addresses on envelopes. Despite Clara’s destitution, her family continues to prioritize Valentino, catering to the shared delusion that he will become a successful doctor one day. Caterina, the narrator and Valentino’s other sister, recounts how her father especially is convinced Valentino will become “a man of consequence.” But Valentino is indolent, prone to idolizing himself in the mirror instead of studying: “He would don his skiing outfit and admire himself in the mirror; not that he went skiing very often, for he was lazy and hated the cold.” Valentino then shocks his family with the announcement that he is marrying Maddalena, a wealthy, older woman. Maddalena is “short and fat,” has a moustache and already greying hair, and is “ugly, as ugly as sin.” Despite the family’s protests, the marriage proceeds. Valentino remains unmotivated and selfish, and it is Maddalena who becomes the support that Valentino’s family needed.

In Sagittarius, Ginzburg presents us with another tale of money — whereas Valentino is a tale of suddenly coming into it, Sagittarius is one of suddenly losing it. In the novella, a widow moves to the suburbs after her husband’s passing, taking her two daughters and son-in-law with her. But quickly she grows restless in her new home. The widow soon establishes a friendship with Scilla, a mysterious designer who shares the widow’s ambitious nature, and the two make plans to open a boutique-cum-art gallery. But Scilla may not be exactly who she says she is, and what proceeds is another story featuring the dissolution of a family, and the role class — or greed, really — plays in its downfall. Both novellas, in addition to presenting themes that recur in Ginzburg’s oeuvre, are excellent showcases for what exactly makes Ginzburg’s prose so alluring.

The language Ginzburg employs is often simple — it is economical, but it is not without magic. Her sentences are spare, and her descriptions exacting, rarely florid or indulgent. This is never truer than in her character descriptions: “I glanced at Kit’s slightly comic profile with the balding head topped by a little beret and the rather pointed nose,” she writes of Valentino’s friend. But Ginzburg can be impassive at times, too. There is a distinct hardness to her prose. This style seems to work in agreement with the tragedies within the stories, as illustrated when the hardness of her sentences matches the hard edge to the action. Take the birth of one of Valentino’s children: “Maddalena’s third child was born. It was another boy and she said she was glad that her children were all boys because had she had a girl she would have been scared that it might have grown up to look like her, and she was so ugly that she would not wish that on any woman. She had become reconciled to her ugliness.” Despite her deceivingly plain language, there is something spiky and shockingly elemental that unravels here, which is the simple truth of Maddalena’s self-awareness. The manner in which Ginzburg pivots from the birth of a daughter to Maddalena’s unattractiveness is hard and ugly, like hitting the reader with a hammer. She takes an ordinary scene and uses it to peel away at a character’s vulnerabilities. The result is a more brutalist take on the domestic. While these novellas are funny, her characters do often meet the most crushing of fates. Ginzburg’s approach is one of cynicism, perhaps even fatalism, which is only intensified tenfold through her brusque prose. Ginzburg doesn’t dwell on loss, either. Devastation occurs and the story proceeds; she trusts us to know that the emotion is there, which is confirmed by the ways her characters are changed.

Valentino and Sagittarius are, ultimately, both stories about family, a domain in which Ginzburg excels. Her families consist of characters that are naive, certainly a bit delusional — perhaps even willfully ignorant. But there’s credibility to the world painted by Ginzburg because she fills in the minutiae of daily domesticities, with all its banalities, so the developments that proceed in each tale feel true. Both novellas are narrated by daughters who are observant and at a remove from the developments of the story. That the narrators are somewhat detached feels necessary for the humor conjured by Ginzburg — it would be almost too cruel otherwise. She favors repetition, too, in an effort to push this near-absurdist mood central to both novellas. That Valentino was destined to be “a man of consequence” is repeated over and over again throughout the novella, making it all the more humorous, and all the more difficult to ever imagine; the lazy, self-centered character presented to us from page one could never be “a man of consequence.” This device of repetition is central to her novel Family Lexicon, too, in which Ginzburg, so well-versed in the idiosyncrasies of her family, has go-to responses from her mother and father ready for a variety of situations. For example, Ginzburg writes, “When [Gino] came home after an exam reporting that he received an A, my father would ask, ‘What do you mean you got an A? Why didn’t you get an A-plus?’ And if he did get an A-plus, my father would say, ‘Oh, it must have been an easy exam.’”

Her parents’ preference for the use of “jackass” as an insult, their near-constant mention of indigestion, and every so often wondering whatever happened to a character named Skinny Shins are the hyper-specific details that make Family Lexicon sing. About her mother, Ginzburg writes: “She used to always buy a certain kind of apple, which in Turin was called carpandue. She’d say, ‘They’re carpandues!’” Ginzburg gently pokes fun at her family’s peculiarities by referencing this specific kind of apple throughout the novel again and again. This is the lexicon of her family, and she presents her novellas with a similar kind of realism. By filling in these more mundane aspects to family life, Ginzburg enriches the story, keeping it in the realm of the believable. I am inclined to believe the stories are inspired by events that occurred to someone in Ginzburg’s life.

The past few years have witnessed a renewed interest in Ginzburg’s fiction. The Dry Heart (1947) and Happiness, As Such (1973) were both reissued by New Directions in 2019. Ginzburg is likely best known for Family Sayings (1963), which was also reissued in 2017 by New York Review Books Classics as the aforementioned Family Lexicon, and she is also celebrated for her book of essays, The Little Virtues (1962). She has found proponents in Zadie Smith and Vivian Gornick, too, and I cannot blame them, as Ginzburg displays a clear ferocity to language. Her voice and style are distinct, with prose that is unique for its simplicity and directness. Though her prose is unsentimental, it is never cold. Perhaps it’s pathos that keeps Ginzburg’s work from ever becoming mean. Her fiction is peppered with dry observations, but evoke immense loss and devastating grief. Perhaps that is also why her writing never veers into farce. Are these nothing more than simple stories of desperate people in search of self-betterment, love, and affection? Are those not the most human of desires?

At the end of Valentino, Caterina says, “I can never remain angry with Valentino for very long. He is the only person left in my life; and I am the only person left in his . . . I rejoice in his beauty, in his small curly head and broad shoulders. I rejoice in his step, still so joyful, triumphant and free; I rejoice in his step, wherever he may go.” Towards the end of Sagittarius, the widow protagonist believes she sees Scilla in the street, and finds that instead of being purely angry at her, “she was surprised to discover a stirring of pity for the poor yellow bob.” The novella then concludes with the birth of the widow’s grandchild. Both novellas end on bittersweet notes. Ginzburg’s characters have suffered, but have learned from this suffering, and have discovered how to value what was always there to begin with — family.

Josh Vigil is a writer living in New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.