The following is from the latest issue of the Full Stop Quarterly. You can purchase the issue here or subscribe at our Patreon page.

To recognize one’s life means first to know what parts of it were not life at all.

—Heimito von Doderer, “My Nineteen Curricula Vitae”

Normally in this world things come to nothing, but here there will be an end, definitely, definitely!

—Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Devils

In Book 1 of the Odyssey, Athena pauses at the threshold of the house Odysseus left. The goddess is disguised as an old family friend; she has come straight from Olympus, having convinced the other gods it is at last time for the hero to come home. We readers have followed her here, and as she reconnoiters we get our first glimpse of the world of Odysseus’s wife and son, Penelope and Telemachus. They have spent twenty years living in the uncertainty of Odysseus’s absence, and at least the last four in an uneasy stalemate with the indolent suitors—dozens of them—who have smelt opportunity in this family tragedy. In a few lines Athena will enter the house and set the long-silent machinery of narrative turning again—George Chapman arms her with a “great, massy, active” spear for just this purpose. Soon enough recognitions, confrontations, and bloodshed will happen in this very hall, but none of the players, the mortal ones anyway, know that yet. For a moment we can see whatever their daily life has come to consist of. Emily Wilson translates:

There she found the lordly suitors

sitting on hides—they killed the cows themselves—

and playing checkers. Quick, attentive house slaves

were waiting on them. Some were mixing wine

with water in the bowls, and others brought

the tables out and wiped them off with sponges,

and others carved up heaping plates of meat.

Telemachus was sitting with them, feeling

dejected.

This is not the purposeful bustle of a great manor, but something more like an airless museum diorama. It takes no imaginative effort to fix the scene in the black-on-orange of an Attic vase: no generative activity, no conversation, the only animals in sight are dead. The impression is that Telemachus and the suitors have been sitting like this for years, frozen in the most energy-efficient gestures of antipathy. Their poses teach us their essential character: The suitors are frivolous and entitled (they have even begun to decorate the place), Telemachus is a sullen adolescent, hostile as he dares to be without actually engaging these men. Although they appear to be sitting together, Homer interposes four lines of motion between them, trapping them on opposite sides of a river. That action—the only action—is the slaves’, quick and unobtrusive, trying to maintain some kind of life for masters who seem to have given up on it.

Here is a household on the brink, then: depleted, stagnant, atomized. And its mistress—where is Penelope? Her absence is another clue things have gone terribly wrong. She only appears once Athena has left, unable to be in the same room as the goddess who brings hope and the possibility of action. And when we do see Penelope, she seems utterly defeated. Wilson emphasizes her fragility, as if she can barely walk: “She clambered down the steep steps of her house, / not by herself—two slave girls came with her.” She has not come downstairs to cry to the gods for justice or to excoriate the suitors’ behavior. The bard is singing of the Greeks’ homecoming from Troy; would he please change the tune, something not so upsetting. This is the level of control she feels able to exercise at the moment.

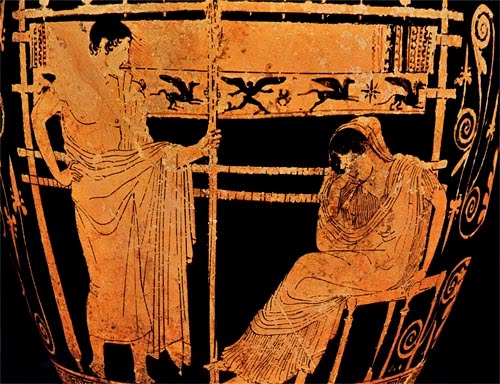

She is a long way from the woman who mocked and held off the suitors for years with her ruse of the shroud, her weaving and unweaving. That was a triumph, however strange and temporary, but she has little to show for it. “I have no more ideas,” she tells the disguised Odysseus in Book 19. Back with the bard, Telemachus tries to encourage her in his coarse way. Galvanized by Athena, he tells her to “go in and do your work. / Stick to the loom and distaff.” Grief, he is saying, is the opposite of work, and of life. Yet another indication of how deeply broken the house is—Telemachus does not just give his mother lip, he speaks as though she is on the other side of the grave.

We can piece together a little more of Penelope’s state of mind. She is isolated, even by the standards of this house, having all but abandoned the public-facing part of it and retired to her private chambers upstairs. When she next leaves her room, in Book 16, it takes great effort: “Penelope / decided she must show herself to these / ungentlemanly suitors.” She has no help from her father-in-law Laertes, who has retreated to the countryside to wait for death, his depression if anything deeper than hers. Then there are material worries. The resources of the estate are “decimated,” a little more of her son’s patrimony disappears at the suitors’ table every day. (They know this: In a parody of the Iliad, they view themselves as a besieging army.) Her family is pushing her to give in and marry one of them.

Above all, her pain is always present and easily stirred up, the bard’s song briefly sharpening what she must always feel in the house she shared with Odysseus, surrounded by men who are present only because he is absent. “I miss him all the time—that man, my husband,” she says, and that grief is compounded by her fears for her son and his future. When she learns Telemachus has sailed away to find news of his father, she breaks down. “The house was full of chairs but she could not / bear to sit upright,” Homer says, putting her at odds with the palace, a stranger in her own home.

It is a fitting image. Penelope cannot be comfortable anywhere, not even in the numbness of prolonged grief. Homer embodies in her the vacillations of the anxious mind. As she worries for her son, she is pictured as “a lion, caught by humans, / when they are clustering round him in a circle, / trying to trap him.” She longs to hear word of her husband—Telemachus mentions she consults with soothsayers—but doubts anyone who offers it. She “will not trust travelers who claim to bring [her] news,” says Eumaeus the swineherd. A bitter strength rises up in her when Odysseus, in disguise, prophesies his own return:

Well, stranger, I do hope

that you are right. If so, I would reward you

at once with such warm generosity

that everyone you met would see your luck.

In fact, it seems to me, Odysseus

will not come home. No one will see you off

with kind good-byes.

Years of waiting and failed predictions, with no clear end to wait for, have inured her to hope. She is not so far, really, from the episode of the shroud—the weaving and unraveling reflects her restless thoughts and her dwindling wealth. Her burdens, both material and emotional. Chapman sees this: “oil and watch it cost, and equal pain,” he has her say of the work.

It is hard to resist interpreting, this shroud. Critics have suggested Penelope’s unweaving is an attempt to undo time and death, to set all as it was before. Or else she is holding off the future, keeping possibilities open. It is a way to cultivate autonomy and power over men (in myths, weaving is a woman’s way of speaking), it is futility and obsession foisted on her by a male author. These possibilities all suggest the shroud is about doing something, that it expresses some desire of Penelope’s. Instead of any of this, Harold Schweizer sees it as a “public account of waiting,” both the purposeful waiting that has an end in mind, and the anxious, unstructured kind. The one unravels into the other, and we start again the next day. This is the experience of waiting: wanting to be doing something but knowing it won’t mean anything—the meaning is what we’re waiting for.

“Waiting is a manipulation of time,” Becca Rothfeld argues, “and its antidote is to make time pass . . . to repopulate the vast stretches of undifferentiated blankness with something like events.” This is quite close to Penelope’s own description, via Chapman, of the shroud as “a curious task / that an unmeasur’d space of time would ask.” Seen this way, she is not working with any concrete end in mind—in other words she does not plan to continue the scheme until Odysseus returns or the suitors get bored. She is trying to keep her hands and her mind occupied, to see what will happen, whether anything will happen, if she keeps it up. Possibly, she might even die. We sense she would not find this an unwelcome development.

In a way, she is already dead. Say we experience life, the living of it, as the accretion of meanings, the constant changing of what we think we know. A Greek enough way of thinking—consider Heraclitus and his river (the same Heraclitus, incidentally, who thought Homer should be whipped). If we grant this, Penelope’s unweaving thwarts that process, like scraping the barnacles off a ship’s hull. The distraction of the work steadily shrinks its stakes. Nothing happens to reinterpret what came before, nothing changes, and so, death. (That is the crime of the suitors: not that they court Penelope, but that they have brought the house to a standstill.) What was conceived as a ruse becomes true: She is working on a funerary cloth, her own. This is why Penelope appears so hopeless at the beginning of the poem: The possibility of change has been all but eliminated.

When Athena finally arrives on Ithaca, meaning has been forestalled until it seems impossible. Penelope certainly thinks so; she suspects everything. In the long interview scene in Book 19, where she talks with Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, she resists any intimation that he will return home, seemingly unaware she is speaking to her husband, while he shifts in his chair to conceal the scar that would give him away. They size each other up, testing each other, drawing on all their knowledge of the other to find what each does not yet want to reveal.

Towards the end of their conversation, Penelope tells Odysseus about a strange dream. She is happily feeding a flock of geese when an eagle swoops in and kills them all. She is distraught, but the eagle tells her, “cheer up,” and explains: The geese are the suitors, I am your husband; he will return and defeat them and all will be well. Odysseus (“well-known / for his intelligence,” he is called here, Wilson or Homer or both being unexpectedly funny) says the dream’s meaning is plain, it will happen just as the eagle says. “Ah, my friend,” Penelope responds (in Robert Fagles’s translation, ellipsis in original):

dreams are hard to unravel, wayward, drifting things—

not all we glimpse in them will come to pass . . .

Two gates there are for our evanescent dreams,

one is made of ivory, the other made of horn.

Those that pass through the ivory cleanly carved

are will-o’-the-wisps, their message bears no fruit.

The dreams that pass through the gates of polished horn

Are fraught with truth for the dreamer that can see them.

But I can’t believe my strange dream has come that way.

“Seasoned Penelope,” Fagles calls her at this moment, as though she too were a veteran of war. “Shrewd,” is Wilson’s epithet for her. Penelope has learned not to trust even the clearest signs. And indeed, Odysseus ignores the ambiguity in the dream—why does she weep for the geese?

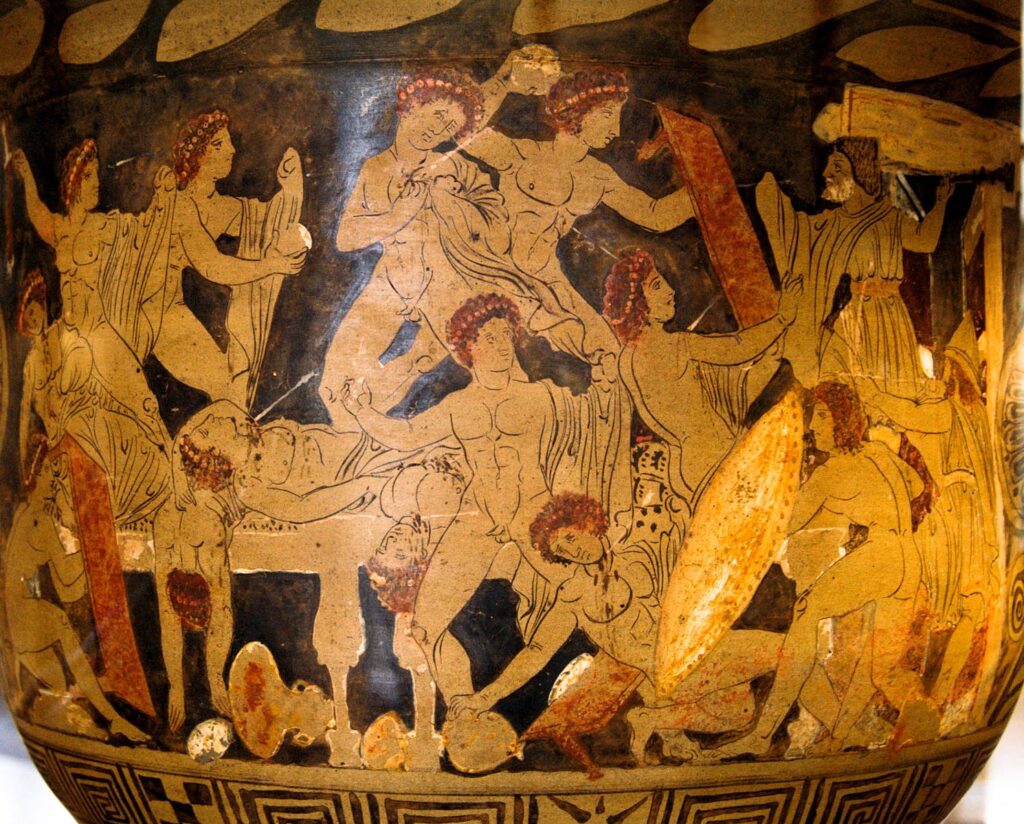

The dream, and Odysseus’s straightforward interpretation, underline the most obvious meaning of Penelope’s shroud, the big irony: She tells the suitors it is for Laertes, who is growing old and will soon die, but of course he will outlive them all. The shroud is, in effect, for their funeral. But like Penelope, they are already dead in some sense. Their life, such as it is, consists of sitting around and waiting to eat. Compare them to the spirits Odysseus finds in the land of the dead, who crowd him “with eerie cries,” thirsting for the blood he has spilled to draw them. Like the suitors, like Penelope, time does not pass for the dead, they have ceased to move towards any goal, what meaning their lives had is fixed and final. Achilles’s terse summary of Hades fits the palace on Ithaca just as well: “numb dead people / live here, the shades of poor exhausted mortals.”

In the world of the Greek epics, a person lives through their deeds; this is why the dead are so concerned their memory endures on earth. (Tiresias’s prophecy of Odysseus’s long walk inland with an oar is a moving image of extreme old age: You travel until no one recognizes anything about you.) The poems are not built for inaction, their heros are always doing, never pausing or reflecting, never really thinking at all. Odysseus is crafty, but the schemes burst forth fully-formed from his head like Athena herself, and are put in action the moment he speaks them aloud. When they go awry, he does not question them. Even Achilles, sitting out the battle and brooding, is doing something—namely, proving a point—and the Iliad becomes heavy with the gravity of his choice. He is no more inactive than a black hole.

The irresolvable, pointless waiting of Penelope is something different, and may as well be death, a connection she makes plain: “I waste my life in longing,” she says. She is not alone—when Odysseus is stranded on Calypso’s island, Homer sets him weeping by “the fruitless sea.” He has stalled out. The underworld sequence in the Odyssey contains our first mention of Sisyphus and Tantalus—punishments of futility.

The experience of waiting, its manipulation of time, is similar for the living and the dead. It dilates the present so neither the future nor, strangely, the past are conceivable. Penelope cannot finish nor completely unravel the shroud. Like the suitors, she does not see, or does not wish to see, the plain meaning of omens when they appear. Nor does she speak of the past—nobody in the house does, not really, except the loyal old slave Eurycleia, who recognizes Odysseus by his scar. And when the suitors have been massacred and herded down to Hades, Agamemnon and the veterans of Troy are baffled by the arrival of all these young men. “Why have you all come down here to the land / of darkness? You are all so young and strong,” the dead king asks, as if he and the others had not themselves witnessed and been killed in similar slaughters. From a certain angle they anticipate Beckett: If we wait long enough, we won’t just forget what we were waiting for, but who we are.

That threat always hangs over the poem, no less painful for being inevitable (Odysseus travels to two places that expect him: Ithaca and Hades). There are special punishments after death for those who have crossed the gods, but no special blessedness, no heaven. “I would prefer to be a workman,” says the shade of Achilles, “hired by a poor man on a peasant farm, / than rule as king of all the dead.” The Greeks “are even more aware than we are of a ruthless fate,” wrote Virginia Woolf, not a decade after the four-year catastrophe then called the Great War. It is that threat, she thought, the cessation of meaning and the knowledge it must come to pass, that accounts for the raw, unforced power of their literature: “There is a sadness at the back of life which they do not attempt to mitigate.” By mitigation, she means, among other things, “the Christianity and its consolations of our age.”

It is certainly a pre-Christian, pre-modern world Penelope and Odysseus live in. Their gods are “essentially devoid of any ethical quality whatsoever,” says M. I. Finley—when they help or hinder someone it is to aggrandize themselves, not to enforce any kind of absolute justice. Whatever morality obtains in this world is made by mortals and is mostly limited to the defense of one’s honor and family. The circle of concern does not get much wider than that (though the care shown to strangers is as admirable to us as it was to Homer). The Odyssey is so far in our past it does not even contain the idea of a community—the residents of Ithaca do not show much concern for Penelope’s troubles, let alone the “confraternity of the human type.”

Those slaves we first see scuttling to prepare yet another feast, for example, for whom life never stopped, are unremarkable in the world of the poem. When they are bad they are scolded by Penelope or Odysseus, if they are very bad they are killed. If they are good they are rewarded and sometimes pitied but never freed. Odysseus, listening to Eumaeus’s story of noble birth and kidnapping by slavers, never connects his own suffering and longing for home with the swineherd’s, and Eumaeus expresses no greater wish than to see his master again. Nor does it occur to Penelope that the repetitive, endless task of weaving she has imposed on herself has some similarity with the work she and others impose on her slaves every day. Her failure to see that—and not just hers, but also her era’s—perhaps contributes to the brutal deaths of the disloyal servants at the hands of Odysseus and Telemachus. The mercy that might counter patriarchal violence has not yet arrived on Ithaca.

To note this is not to fault the poem; Homer is faithfully representing his world and its way of seeing. It is simply to point out that “Christianity and its consolations,” the morality they inaugurated and which Woolf found so hollow, have led us to see things Homer could not imagine or comprehend, and that a world where they were fully jettisoned would horrify us. They mitigate more than powerful aesthetic effects. “Our grief is not Greek,” says W. H. Auden in a poem written after a later, even more catastrophic war, and it can’t be. “We know without knowing there is reason for what we bear,” he continues. However pointless our waiting may get, however stark the isolation it occurs in, there are possibilities, yes, consolations—“solidarity” is one, “hope” might be another—open to us, distant as they are, that offer the change and consequence denied to Penelope. That distance itself—now closer, now farther—consoles, for it means there is always work to do, and it proposes a vision of death that does not sever our connection to these ends, but may epitomize them.

Odysseus returns, slays the suitors, reunites with his wife. Her waiting comes to an end, but whether life can revert to the way it was before is unknown. The poem can’t tell us; it is a war story, and so it ends the moment the last Achaean veteran finally puts down his arms, not knowing how to speak of a world without violence and deceit. Yet Finley draws our attention to a moment after Odysseus has killed the last of the suitors. Eurycleia enters the hall and rejoices at the carnage, but he stops her: “It is not pious, gloating over men / who have been killed. Divine fate took them down, / and their own wicked deeds.” For a few lines, faint notions emerge that a dignity may inhere in the human person, so powerful it hangs about a corpse; that even death has its meanings; that we might order our lives to something other than our own will.

Mark Clemens is the winner of the 2018 Bodley Head/FT Essay Prize. He lives outside Chicago.

This post may contain affiliate links.