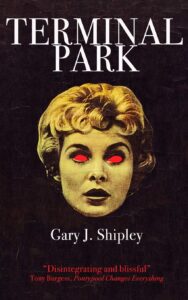

[Apocalypse Party; 2020]

“An apocalypse does not end so much as uncover. It’s an epistemic revelation, a disclosure of secrets, a divine correction manifested in the world. It shocks us into submission, and from here we see how the world as we imagined it falls away. The end of the world is no more than the end of the world’s conforming to our cognizance of it. The apocalypse is the truth in a place that’s systematically allergic to the stuff.”

Confined to a tower, Kaal watches the end of humanity. Population growth, the depletion of resources, and the more general befouling of earth are accelerated by the phenomenon of “splitting” — the tearing of the body into two identical, or near-identical figures. Once the splitting starts, and split humans split again, populations grow steeply, grotesquely, and reproduction becomes an irrelevance. Kaal watches the decay of order from his balcony, and on screen.

At the same time, Kaal becomes locked into a differently horrific video diary created by an artist in residence (and hiding) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, holed up in Cornelia Parker’s Hitchcock-inspired “PsychoBarn.” From this vantage, NB, the occupant, observes how horror is fetishized, rendered banal, and finally “understood” by the shuffling visitors to the Met. But NB also returns insistently to horror, observing from the roof of the Met a repeated and brutal murder in the park below, as if the world was stuck in “pause rewind and play,” or some kind of highly localized, shortened, and thereby doubly impossible eternal return. Meanwhile, Kaal sits and watches NB, and looks outside, as populations grow exponentially, the splitters taking over the earth. The surface, and certainly the streets below are eventually covered by their writhing mass that rises up, and then descends into mush.

There is much to comment on in this extraordinarily rich, philosophically driven novel. Here I focus on one particular aspect, its treatment of nihilism, the ontological convulsion brought about by the death of God. One element of that convulsion — of the still-enduring effects of the death of God — is the endurance of sentiment and the value of reason, the insistent demand that the world must still make sense and yield to human value. A nihilist, Nietzsche writes, “judges of the world as it is that it ought not to be, and of the world as it ought to be that it does not exist.” Nihilism is bound, in other words, to values and futures it can never realize. At the same time, it is typified by a refusal to accept, to see, without sentiment, without reason. Nihilism might be characterized here as a determined inability to accept that which will not comfort, or console, or offer itself up as decipherable. It is not easily overcome — nihilism still frames our experience.

With Terminal Park we travel to the edge of this experience, held there, perhaps, by a tussle between horror and recoil. In this novel, Gary Shipley depicts the lowering of human life to the suffering, visceral experiences of bodies without sanction and without escape. Throughout the book, Shipley (as one might expect from the author of Serial Kitsch), works hard to keep horror in view, against its reduction to the familiar and the banal, to the trope. This is Shipley’s labor against nihilism, against its abject securities, against the tendency to retreat from uncomfortable realization, to the comforts of the familiar.

Terminal Park describes the destruction of humanity as it returns to “an undifferentiated black pus . . . the raw effluence of being.” This is the underpinning stuff of existence which “our fabricated humanity” will not see, cannot see. This humanity has indeed constructed itself so as to never see this “ooze that absorbs all our feeble extrapolations and exudes nothing but its own entropic glut in return.”

The earth is strewn with bodies. Countries, continents, seas change color. Cargo planes fly over Siberia “laying pathways of bodies on the permafrost,” in patterns, we are told, that serve “no other purpose than to distract” their pilots from the murder they perform; freighters are sent out to disgorge thousands into the waves: against which, individual murders, even those that might kill others by accident, such as defenestration, lack impact.

All of which is observed by Kaal, an ex-philosophy professor, looking down from one of the towers where the survivor sits, apathetic to the point of extinction, his mental faculties eviscerated, but continuing to output thought; a warped but not entirely unrecognizable figure to those who work in universities today.

When the first signs appeared, Kaal managed to trick his way into the tower by the corruption and influence still afforded him by his position — he offers to bestow an honorary degree on “a conveniently conceited multi-billionaire tech impresario, who’d had no trouble believing he’d be in line for such an accolade.” We find that the university still stands, and graces the world with its honors, at the dawn of apocalypse.

This novel is based on an apparent inversion. “What had been the epitome of inhumanity fast became its opposite. For those that did not kill were not only failing themselves but all humankind.” When depopulation, the eradication of most humans on earth, was elevated to highest aim, there could be “no civilians, no innocents, no crimes against humanity . . . In the end, the only deviant behaviour was paralysis.” Gary Shipley has this transformation, this desecration of all recognizable systems of value, described as a “moral inversion” and presents the reader with the disturbing fact that within the orbit of Terminal Park, within its universe at least, that moral inversion was readily adopted. This raises the question of how inversions happen, or if they are inversions at all.

Apocalypse in film and fiction is not uncommon, but what marks this book out is that not even a slither of sentiment remains. The proximity of horror is assured by a suspicion that the world of Terminal Park is not so very far away at all, and that the inhumanities depicted here are not so much an inversion, as the extension, or to adopt a phrase Shipley uses, that they are the logical effect of a state of abjection that is “not new, just out of hiding, just scoped beyond former possibilities.” This novel — grotesque, unbelievable as it may be (“At around five quadrillion the crust of the earth has its own human skin.”) — presents destructive tendencies, machineries, logics, already familiar in our present, even if these familiar tendencies do not shock, awe, and stupefy, as they perhaps should, and only reach the kind of pitch of necessary repulsion in a book that for most tastes is far beyond the pale.

For many it will be too much to suggest that when Shipley writes: “Humanity’s greatest achievements, its sciences its arts its literatures its technologies its moral codes, all met . . . in the warm engine of death,” he is not referring to the radical transformation of the sciences, arts, literatures, technologies and moral codes. It will be too much, for most, to suggest that Terminal Park does not stage the transformation, the inversion of their mission, but a revelation of their malice, their violence. At the center of the book a work of art turns, indeed, to violence, to murder, to putrefaction, but this is nothing in the scheme of things. People will still gather, when gatherings are still allowed, to enjoy and savour the spectacle (admiring the flies that arrived at the Met roof installation, and that came to swarm, for “their invocation of the swamp,” for adding a touch of “authenticity,” it was “an interesting flourish,” a “nice touch”).

Or, to think this differently (and more palatably), it is tempting to see in this book an account of the co-option of the sciences the arts the literatures the technologies and the moral codes of humanity, and hence to read the reassignment of all culture, all science, all civilization to the purpose of death in Terminal Park, as a case for their collective inability to block apocalypse.

Terminal Park stages the failure of systems of value and restraint that will be inadequate in the face of human desperation, cultures that will at best evaporate during the struggle to live on an over-populated, ruined earth. In the book they fall almost immediately.

Against the challenge set out, here, by Terminal Park, those who reject its morbid, visceral obsessions, those who speak on behalf of higher principles and better tastes, those who celebrate humanism and culture as effective agents of peace, who declare that this or that value will and must be the last (in their minds) to fall, betray either poor understanding, or the extent of their willed/unwilled self-deception. Probably both. The sorry fact is that the world will continue without them, indeed, as Shipley writes, it will reach a point where “the abject authenticates itself through necessity.”

Systems of value are, of course, vitally important to the humane treatment of individuals, of societies, of one another (even if they never quite guarantee what they promise). But they offer no ultimate security in the face of desperation. There is work — speculative, daring, creative — to be done at the fringe of culture, and at the borders of humanity, where questions can be posed in a manner that none will accept.

It is worth underlining the point that when viewing the world from the comfort of culture, and the security of belief — automated, or sincere — we cannot even begin to wonder what might be required to equip, to train, to prepare, and most importantly, to confront oncoming apocalypse. Terminal Park offers, I think, an intervention here, of this kind, and at this level of urgency. Kaal offers no answers, and no model to live by. And yet, the spectacle he confronts demonstrates that humankind will only know what to do, will only realize itself in the singularity of its purpose, when it is already too late. In the meantime, all preparations will be piecemeal, ineffectual, which is no argument against them. This is the only place left to inhabit.

Ansgar Allen is the author of several books, including two novellas, Wretch (Schism, 2020) and The Sick List (Boiler House Press, 2021). He is based in Sheffield, UK.

This post may contain affiliate links.