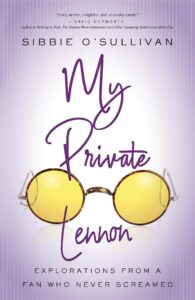

[Ohio State University Press; 2020]

The precept of Rock Criticism was to take the music seriously as a matter of vocation: to legitimize an illegitimate cultural form through strategies of analysis and attention. Sibbie O’Sullivan begins her book, My Private Lennon: Explorations from a Fan Who Didn’t Scream with an assault on those men who first heard the call of rock criticism: Greil Marcus, Robert Christgau, Lester Bangs — the Father-Father-Holy Ghost (RIP Lester) Homosocial Trinity of Rock Crit. Through styles of scholasticism, wit, and bombast, each elevated the music. What other word is there for what they did? They took the music seriously in the way they knew how: to listen carefully. But O’Sullivan reminds us that the Beatles were already taken seriously, not by media but by fans: always legions, teeming, screaming, legions of female fans: girls, finally. That demographic whose wants were most ignorable. Girls who shrieked in an ecstasy so unknowable to the male gaze, so opaque and un-intuitable that the boys, reacting against it in irritated befuddlement, packed up their game and went home to study their records.

If you open up the original Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll the first double-spread image you see: black-clad cops, holding back a mob of people. It’s a little alarming. You might miss that there are no looks of menace in those police faces. In 1968, the MC5 headlined the Festival of Life in Chicago playing opposite the Democratic National Convention (a spectacle of death). They were the only band to show up after weeks of threats from the Mayor of Chicago, Richard Daley; the police had been given orders to shoot to kill and there would be violence if protesters came to his city.

He was right. Police smashed the Festival of Life, smashed the MC5, smashed protesters, and smashed convention delegates, smashed reporters. Dan Rather was punched in the face on the convention floor. Against the chants of “The Whole World is Watching,” police chanted “Kill, Kill, Kill” broadcast for the first time on national television. Even the official autopsy of Chicago 1968 labeled it a “police riot” (notwithstanding how well coordinated these attacks were).

My point is: police and rock music are linked together, and even if rock musicians have always been a bit more posture than put up, there was in the 1960s an at-least-aesthetic glue which bound social protest to the groove.

Midway through the History and we get another piece of the picture. A police officer is holding a woman who has fainted and opposite we see the chapter title “The Beatles,” and you realize this isn’t a riot.

There’s a glimmer of possibility in the visual confusion between the riot and the massed fanatics, a confusion that was maybe less categorical then than it is now (see the reference in the ‘60s to “moral panics”). After all they both produced the police, those enforcers of middle-class mores and property values. While the boys made the case that The Beatles were worth serious consideration through suasion, the point was already moot. All those unruly bodies gathered together are an extremely legitimizing force.

Sibbie O’Sullivan didn’t scream, but the power of her writing stems from how seriously she takes the people who may have. Boy theories of the female scream run the gamut of patriarchal self-delusion. One such example posits that it was a kind of motherhood lust — a rehearsal for all the excitement of conception as if the teen-age woman calls down from eternity the cells to propagate her future offspring. This was the 1960s and the mysteries of female heterosexuality were obviously still quite mysterious to men. The force that motivates so much of this book is just that: against a culture of stupidity and chauvinism which never asked nor took those women seriously, what thing were they responding to?

In part the answer is obvious, which is to say sexuality:

Imagine running your hands through a Beatle’s hair, pulling it back off his forehead! There’d be a big payoff in that: their faces, and what fabulous faces they were — real, released from cosmetics, flawed. Consider the inside fold-out photo on the Beatles for Sale CD: their heads and brows covered by hair, their necks by coat collars, but the band’s faces are a revelation. Intense and challenging, all unsmiling; no one would use the term “boy band” to describe these faces, as they clearly belong to men, their smoky, mysterious power capable of arresting the viewer.

The Beatles in some way offered themselves to be viewed, to be ogled and admired, to be lusted after. To frame it even in this way, however, is to give so much precedence to the object. O’Sullivan does not just recount a story of the Beatles; it is her story, the meaning which she made from them. In its germinal form this is permission taken, not just granted. O’Sullivan writes, “One power a fifteen-year-old female fan had was the power to look, to stare, to gaze, to be transfixed by male beauty, something ‘good’ girls only did in private.”

Beyond the initial joy of public sexuality, O’Sullivan centers the fan as someone who, though she has no claim to the public, experiences life just as much as the artist and who makes sense of that life with the tools furnished by public art.

While O’Sullivan can be as polemical as any good critic (my God, does she need to call Lester Bangs a junkie?), the collection takes on a form that is almost unfamiliar in today’s context of critique. Without claiming universality, she writes about her life as it is drawn by the touchstones of experience of a straight, white woman: the bad dates, the cringy boyfriends, the secret knowledge shared between her girlfriends which evolve into the creepy and controlling men, the spiraling from yourself that pregnancy brings, the sense of loss at failed marriages. It’s not that these experiences are exceptional, but so often they are merely ignored as massified, lacking mystique, or cultural cache. Which is why The Beatles, as probably the last cultural commonplace, at least for white Americans, become a kind of public language through which to understand these common, often private experiences.

Through telling the life of John Lennon, who experienced the death of his mother at a young age, O’Sullivan writes about a mother who was at first distant and then gone. As she wonders how in the space of absence longing might curdle into something more taboo, she writes about a father whose one-time inappropriate touch remains fixed, ineradicable in memory. In the Sixties she mirrors The Beatles own growth into confusion and end of innocence; as she grows from them, she realizes the spaces in which a woman is supposed to be are delimited by the predation and menace of men. Of Richard Speck she wonders, “How could eight women not fight off one skinny man? Eight men certainly could. Despite imagining being the nurse who escaped death by hiding under a bed, our inability to answer that question manifested itself as an ugly reality: all women, one way or another, are marked.” And as the Beatles find their own, individuated voices, she wonders if she might not be a writer, a scholar, a poet.

While this arc is not totalizing — many women probably would not define their lives around motherhood or around sexuality — it represents a kind of mathematical mode of experience — a defining and understanding of oneself around the institutions that order life, in some cases order with authority and coercion. Rarely are we as exceptional or rebellious as we would like to be, but rarer still is the person who admits to living in the ambivalent space seeking love, seeking comfort, even when it is not always good to us.

The standout essay in this collection is O’Sullivan’s “Aeolian Cadences.” The term is one applied by a classical music critic to a song by the Beatles — an early example of one particular strategy of legitimization: the Beatles are good because they are classical. O’Sullivan’s romantic partner, whom she refers to as The Man I Love, is himself a musician who quickly dismisses the term as being nonsense. The ensuing fight, in which O’Sullivan struggles to extract some definition or understanding from her more knowledgeable partner and to which he responds like (excuse me) kind of an ass, leaves O’Sullivan thinking hard about a knife she has in her kitchen drawer and how it might look planted in him.

But the rhythm of this encounter, rooted essentially in an infelicity of language, is so perfectly mundane, comic, and maddening. It reveals the way pop culture becomes a kind of palimpsest for all kinds of other connections and misconnections between people. Dave Hickey, another music critic, talks about the importance in a polymorphous democratic society of pop music as giving us fractured moderns some language in common: “Because it’s hard to find someone you love, who loves you — but you can begin, at least, by finding someone who loves your song.” Maybe things are not so harmonious as all that in the fraught and sometimes terrorful negotiations of men and women in straight worlds. What better analogue for this mixture of confusion and connection than the scream of revelation experienced by a fan? Still it’s only the surface of things. Eventually, O’Sullivan and her man come to terms and O’Sullivan to this soulful, wounded understanding of the feeling: “Love inhabits the distance between a wish and a fact, a space held in place by the competing gravities of joy and disappointment. He stayed. I stayed.” Somewhere, there in the house, is a Beatles record.

M. Delmonico Connolly is a graduate student at the State University of New York at Buffalo. He writes and revises sentences about race and pop after the Civil Rights movement and is the author of the forthcoming chapbook, Ronnie Spector in Rock Gomorrah at Gold Line Press.

This post may contain affiliate links.