The following is from the latest issue of the Full Stop Quarterly. You can purchase the issue here or subscribe at our Patreon page.

1.

Then the hail came with the dark, setting up a staccato drumming on the corrugated metal roof. My poor daffodils, which greeted me on my return, are now beaten to the ground.

~

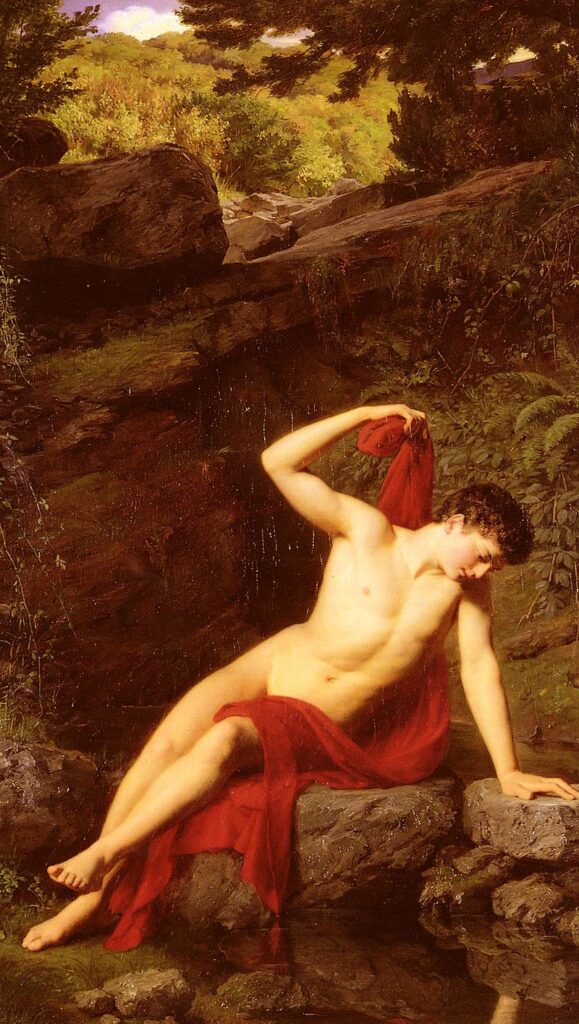

Narcissus is derived not from the name of the young man who met his death vainly trying to embrace his reflection in crystal water, but from the Greek narkao (to benumb); though of course Narcissus, benumbed by his own beauty, fell to his death embracing his shadow.

— Derek Jarman, Modern Nature: The Journals of Derek Jarman

In one version of his story, Narcissus refuses a succession of admirers, including a young man named Ameinias. Narcissus, beleaguered by the unwanted attention, gives Ameinias a sword, and asks to be left alone. Before stabbing himself with the sword, Ameinias puts a miserable curse on Narcissus: he will never have the object that he desires, and that object will be himself.

Narcissus’s downfall was not vanity. Or we could say that it was, emphasizing the destitution inherent in the word (from vanus, meaning empty). The curse emptied Narcissus of his ability to know that his body was his. He was left unable to sense himself imaginatively; he had no self outside of his desire to resist external demands. Can we blame him for trying to keep himself together? To decline the longing of others? All Narcissus had, in the end, was his addiction and the excuse that his face was too beautiful. He became so empty that he finally dissolved into oblivion—forgetting everything but his longing on his way to transforming from a man into a fragile winter flower.

Narcissus shows us that appearance is a tangle of other people’s desires, a brace of projections and conditions. In his attempt to escape Ameinias’s toxic obsession (or, in the better-known version, Echo’s harassment, which is so persistent that it outlives her body), Narcissus takes refuge in self-displacement. He finds escape in the refusal of his beauty, but he is dependent on his desire for it. In the rejection of others’ desires, he rejects yet desires himself. He knows and does not know that his face is his, yet does not belong to him.

Derek Jarman’s reading of Narcissus’s tragedy threads self-obsession with anesthesia. Protracted, agonizing longing inevitably exhausts him into dazed distraction. But perhaps identity itself is this unendurable yet durable condition of desperate, intoxicated, lustful denial.

2.

We are constrained by living under duress in a world that is hostile and invasive; we are both reluctantly and willingly invested in using tools and signs that have betrayed us. This betrayal is the loud, unchosen remarks of bodies that signify in spite of our desires—whether conscious or unconscious, deliberate or inevitable. Disloyal, our bodies collude with others’ desires before our own: they give us away, and they fail us by going against our wishes.

3.

The difference between yes and no is often a matter of pressure—answers need not emerge unless questions are asked. Definitions, genres, categories, or diagnoses are not revealed, but produced.

In many places, access to healthcare is still based on the legibility of a person’s narrative: the ways that trans people’s stories are told (chillingly, even to ourselves) are inevitably affected by the manner in which we have been obligated to tell them in legible ways. Manipulating unavoidable institutions has been an important function of trans people’s autobiographies, because we have to live in spite of the impossibility for “justice” on institutional terms.

And so what is memory under the pressures of institutional legibility? The undead systems that unequally distribute life chances determine, accordingly, who gets enough relief from material constraint to know and to remember. Some would-be memoirs are obscured even to their authors, who lack the necessary time, resources, and trusted friends to support and reflect back in ways not laced with conditions that warp desires and hand back fractured selves that we struggle to hold together in order to pay the rent.

I risk coming out at work, and suffer for it. I pass, and rarely come out as trans unless I have to, but I assume that effeminacy must shine out of me. I suspect that I will never convincingly embody proper masculinity, and I preemptively explain this by confessing to dating men. Then I have to attempt to conform to the presumed story that my questioner has in mind. Cornered, and telling lies, I have no voice yet to respond to his questions: Am I sexually promiscuous? How did my dad take it? What was it like for me in high school? Is it wrong, he asks, to prefer for his own son to be straight?

He doesn’t even know I’m trans, just gay. Outwardly, I am calmly compliant, politely reminding him of my boundaries from the border zones between my conflicting desires to get up and leave the room; to tell him to fuck off and leave me alone; to explain in angry but well-rehearsed terms precisely why what he is saying is dangerous and wrong; to maybe ask him, “Why are you so obsessed with me?” All of these possible trajectories twist out of the way because I cannot fight at work. No one has my back, anyway. But if I’m honest, the reason I don’t fight is that I lack the vocabulary to field him with dignity and elegance in a way he will understand.

4.

We Both Laughed in Pleasure—the long-anticipated and newly published diaries of trans writer and activist Lou Sullivan—is a gorgeous account of Sullivan’s transition as he finds or makes the language for his experience. Sometimes he writes with astonishing ease and articulacy; other times, he does so with the kind of tactlessness that would get him instantly cancelled on Twitter. For me, Sullivan’s complexity, vulnerability, and generosity yield a nourishment laced with agony. Amidst his wounds, disappointments, and endless longing, he made me cry with identification and relief.

My experience with Sullivan’s diaries represents just one small testimony to the inarguable crucialness of documents, memoirs, journals, and records of trans lives. But it’s complicated. Since we represent such a threat by exposing the edges of cisgender identity, the burden of proof for our authenticity has been ours at every stage of self-determination. Our stories are keys to access basic resources; we tell them to make ourselves readable—and therefore bearable or deserving—or to account for ourselves in contexts where the slimmest doubt is considered cause to dismiss us. I have a well-rehearsed tale that I tell medical professionals. I have also felt pressure to journal, to be an automatic expert on the perpetually “burgeoning” and affirming field of trans studies, to write essays, to show up at discussion groups, to be active on social media, to document transition, to generally not let the side down.

So I am in sympathy with a friend who has written to me: “I don’t want to write about trans stuff. It’s not you, it’s me. I’m sick of memoir as the primary mode of trans utterance. Aren’t we all, ducky?” Our lives can become hackneyed expositions of discrimination or lists of diagnostic criteria that are, no doubt, fascinating to some. But my friend is not alone in being sick of hearing himself talk.

To suggest a refusal of memoir feels like a betrayal, and it is. It is also impossible. But what if, as my friend suggested (before changing the subject), we got bored of ourselves—and decided to do something else?

5.

In his poem “The Birth of Pallaksch,” Kevin Killian attributes the following quote to Sun Ra: “It has that perhaps and mishaps feeling, of yes I’m wearing it and no, I don’t remember what I’m wearing.”The poem meanders around something called the “Pallaksch feeling.”

The Romantic poet Heinrich Hölderlin reportedly at one point became obsessed with his own translation work, and in a reclusive tower phase, took to pacing, ranting, and endlessly revising his versions of Oedipus and Antigone. Frustrated with the stilted and deadening restrictions of existing language, he began to invent words. He coined pallaksch to mean “sometimes yes and sometimes no.” In Float, Anne Carson writes: “Linguistic invention is a risk. Because it comes across as a riddle and you cannot get behind the back of it. ‘Pallaksch Pallaksch’ has to stand as its own clue, has to remain untranslatable.”

Most of the time we become through ambivalence—not caring either way—in an ill-fitting place of unfulfilled desire. Pallaksch defamiliarizes affirmation: Yes, I’ll be this thing, but no, I don’t know what it is anymore. To stand as our own clues, to stand still, to not understand—this is to shrug off the burden of explanation.

6.

In Sandy Stone’s essay “The Empire Strikes Back”—one of the seminal texts of transgender studies—she argues, in a metaphoric conflation of bodies with texts, that “transsexuals who pass seem able to ignore the fact that by creating totalised, monistic identities, forgoing physical and subjective intertextuality, they have foreclosed the possibility of authentic relationships. Under the principle of passing, denying the destabilising power of being ‘read,’ relationships begin as lies.”

The fact that Stone’s essay was written in response to Janice Raymond’s trans-exclusionary diatribe “The Transsexual Empire” means that a consideration of genre along with gender inherits a reactionary aspect. Stone writes that passing is an “imperfect solution to personal dissonance,” which depends on withholding a narrative of a life lived before, through, and after transition that we ought to celebrate. “Silence,” she writes, “can be an extremely high price to pay for acceptance.” According to Stone, in choosing not to pass, trans people reclaim our bodies. She suggests that we read ourselves aloud, allow ourselves to “be read” in all our faceted complexity.

While the kind of narrative she suggests is explicitly in opposition to the medicalized, hegemonic narrative, Stone’s suggestion remains, in my view, a response to pressures to confess, in the Foucaultian sense. Reclaiming an illusory ownership of the narratives of our historic selves gives a compensatory psychic release that is, in the end, productive, since it knots us more firmly into evaluative systems of power, satisfying our craving for innocence or passivity before an institutional hermeneutic.

Curiously, however, Stone’s notion of reading—or of allowing ourselves to be read—is strangely obfuscatory in its phrasing: “the multiple dissonances of the transsexual body produce not an irreducible alterity but a myriad of [sic] alterities.” So we contain multitudes. But what could Stone mean by “an irreducible alterity”? I am reading against her here—but on a common sense level, there is something fundamental to embodied difference that cannot be simplified, translated, or fully communicated, regardless of whether a person passes. Irreducibility does not exist without interrogation; something that is irreducible or untranslatable is only described as such because there is something frustrating about its illegibility. What happens when we disinvest from the distinction between irreducibility and multiplicity? Proliferation, after all, is another means of hiding: saying yes, but also no, maybe, perhaps, what about it? I don’t know, you tell me, am I?

7.

In his poem “Split It Open Just to Count the Pieces,” Oliver Baez Bendorf uses as an epigraph a quote from Judith Butler’s Bodies that Matter: “One might consider that identification is always an ambivalent process.”

In the original text, Butler continues:

Identifying with a gender under contemporary regimes of power involves identifying with a set of norms that are and are not realisable, and whose power and status precede the identifications by which they are insistently approximated. This “being a man” and this “being a woman” are internally unstable affairs. They are always beset by ambivalence precisely because there is a cost to every identification, the loss of some other set of identifications, the forcible approximation of a norm one never chooses, a norm that chooses us, but which we occupy, reverse, resignify to the extent that the norm fails to determine us completely.

In conversation with that loss, Bendorf’s poem takes the form of a list of names: “Call me tumblefish, rip-roar, pocket of light, / haberdash and milkman, velveteen and silverbreath, / your bitch, your little brother.” Though the title features the derogatory pronoun it, Bendorf asks for names in a precise and promiscuously curious self-exploration that combines utopian whimsy, self-aware cliché, and sexist and racist slurs in a manner that is both violent and celebratory, both bitter and hopeful. Unabashed and playfully imperious, he extends to us the space between what he is and what he desires to be. From a scatter plot of possible names, Bendorf’s voice hails us as allies, companions, adversaries, siblings. Names can be intimate conspiracies, or, as Bendorf’s collection insists, they can let us belong or find solace in promiscuous webs of meaning that extend into speculative, fictional, or animal worlds.

But this proliferation also speaks to the ways that we are determined so forcefully by what others call us, what we can convince people to call us, or what we can get away with calling ourselves. Names are a means of control and a weapon. Names can wound, but so can their absence or removal, since customarily, that which is nameless does not exist. Bendorf’s poem is a site of the cuts, wounds, and fractures that we hold together on pain of exclusion and poverty.

Near the end of the poem, Bendorf references the documentary Paris Is Burning: “Call me and tell me that Paris is on fire at last, / that the queens of Harlem can have their operations / and their washing machines.” Butler’s use of the women featured in Paris Is Burning has been critiqued from numerous perspectives for the way that she privileges queer theorization at the expense of trans-of-color life. Bendorf’s treatment provides an antidote to the perversity of Butler’s implicit disappointment that the appropriation that is inherent to ballroom culture is not always subversive, and that the “irresolvable tension” between subversion and appropriation leads to “fatally unsubversive appropriation.” In other words, she characterizes passing as unpolitical deception. Bendorf draws the bitterness of the violence and neglect that trans people experience into his string of names. With a kind of serene rage, he compares the ease with which he might be called “hand-rolled sea,” “cobblestone,” or “thorn of rose and loaded gun” with alternative histories of longed-for normal life.

Bendorf’s poem closes: “Call me seamless, / call me sir. Call me tomorrow’s inevitable sunrise.” By splitting himself open, Bendorf is asking after that pain. Yet he insists on seamless as a respectful title, akin to sir.

8.

In Alison Bechdel’s memoir Fun Home, she describes the “compulsive propensity to auto-biography” she experienced as a child. Feeling a disturbing and almost paralyzing disquiet at the impossibility of knowing the truth, the ten-year-old Bechdel began to preface every sentence in her journal with a tentative “I think.” This realization of the untrustworthiness of her own perceptions and memory—the recognition that between the written account and the actual event is a “gaping rift”—constituted a crisis that Bechdel could not allow to go unnoted. She writes, “The most sturdy nouns faded to faint approximations under my pen. [. . .] To save time I created a shorthand version of I think, a curvy circumflex. Soon I began drawing it right over names and pronouns. It became a sort of amulet, warding off evil from my subjects.”

Bechdel’s impulse is protective. The evil of uncertainty, the possibility that her memory is capable of a violent misrepresentation, necessitates self-erasure. The circumflex is a curious solution, given that she could have simply stopped writing anything down. She seemed to require the accounts to be written and crossed out. A kind of preemption of being caught; a guilty admittance that attempts to outwit the inevitable future betrayal. Her diary entries became “fairly illegible” or “almost completely obscured” by the circumflex. The word circumflex derives from the Latin for bent-around, and refers to an accent mark used to alter the pronunciation of vowels. In parallel to the story of the diary, Bechdel writes about inheriting her father’s “bumkinish” Pennsylvania accent, and the way that broad diphthongs in her speech were straightened out at college. Similarly, the circumflex is a corrective against what Bechdel had come to see as the untrustworthiness of her own perception. If it is not already overdetermined, the pejorative bent means queer, gay, and/or criminal; bender is both a homophobic slur and a period of time of which one might have a patchy subsequent memory due to intoxication.

Bechdel’s circumflexed childhood guilt is of course highly relatable content for queer kids in a straight family. The kid’s right to self-define is traded for their parent’s peace. They self-correct, self-erase, self-avoid so that they might have their parent’s approval. But the insistent “I think” is as much an expression of defiance as uncertainty. The right on which Bechel insists is the right to doubt, to point out that the Way Things Are need not be true. Yes it happened, but what if it didn’t? And not having anyone else on whom to rely with the alternative, no one to work it out with, Bechdel must turn to herself and repeatedly make space for alternatives.

9.

We wait in the empty street at the stop for Lethe, the only bus that runs both ways. [. . .] To signal to the vehicle that one wishes to board Oblivion Return one must fan open the grille by pressing a button and lighting up the small lantern on the top of the archway, which I did. It’s the one gleam of hope in this world.

— Hélène Cixous, Double Oblivion of Ourang-Outang

In Greek mythology, there are five rivers in the Hades. One of these is the river Lethe; spirits who crossed the Lethe on the way to Elysion forgot their worldly life. We can’t opt out of the awkward declarations and invitations that constitute gender, or we will, like Narcissus, fail to recognize our own outlines. However, the kind of forgetfulness that “runs both ways” leaves space for irresponsibility and relief from the pressures, such as those in trans scholarship, to perform in a reactionary and affirmative mode. The word lethargy is derived from Lethe. In our rest-deprived surveillance economy, I enjoy the relationship between boredom, laziness, and forgetting what you’re wearing.

Kit Copeland is a writer and artist from Glasgow. He works with the Glasgow branch of the Small Trans Library, and graduated from the MA in Aesthetics and Politics at CalArts in 2019.

This post may contain affiliate links.