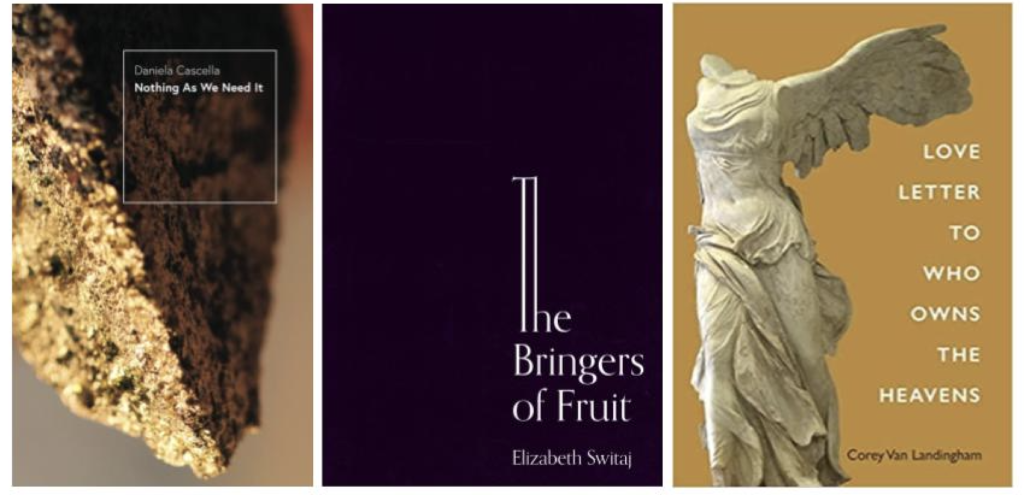

We seem to be in the midst of another neoclassical period. As during the European Renaissance, readers and writers today are returning to the art and mythos of the Greco-Roman classics for inspiration. You might recall the massive popularity of Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians series that began in 2005, featuring modern-day demi-gods and their interpersonal relations. 2016 saw the off-Broadway premiere of the musical Hadestown, a retelling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. In 2018, Olympus by Rachel Smythe explored the myth of the abduction of Persephone and the recent more popular interpretation that her relationship with Hades was consensual. This webcomic, later published as a graphic novel was widely popular and is still ongoing. Most recently, the fully crowdfunded musical adaptation of The Song of Achilles, ARISTOS, has shown how much the community at large craves these retellings. Now in 2022, we’re seeing a new return to the classics in indie lit with such titles as Elizabeth Switaj’s The Bringers of Fruit: An Oratorio (11:11 Press), Daniela Cascella’s Nothing as We Need It: A Chimera (Punctum), and Corey Van Landingham’s Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens (Tupelo Press).

Why do we keep returning to these myths, and what are different authors and artists deriving from them?

In her book Not All Dead White Men (Harvard University Press), Donna Zuckerberg highlights a disturbing phenomenon in which alt-right groups latch onto the philosophies of classical writers as a way of “backing up” their more regressive ideologies. They point to the misogyny and racism of the classical authors and philosophers and see themselves reflected. They want to conserve what they view as the way things have always been. They trace themselves back to an ancient time, while ignoring the more progressive ideologies they might have held.

On the other hand, I can recall myself and my friends finding ourselves fascinated with mythology, eagerly consuming different stories and trying to find ourselves reflected in intelligent female characters, and later discussing the homo-erotic leanings of the Iliad. Now, I frequently find myself and classmates in college English courses comparing modern-day literature to those familiar myths. We are not the only ones to seek a reflection of ourselves in the classics; in her article “Reclaiming My Sister, Medusa: A Critical Autoethnography About Healing From Sexual Violence Through Solidarity, Doll-Making, and Mending Myth,” Rosemary Rilley explores how herself and many other SA survivors find solidarity through myth, finding a reflection of their struggle in the story of Medusa. Medusa’s image has come to represent protection, survival, and safe spaces, largely due to a common rumor that her bust was used to mark women’s shelters in ancient Greece.

Despite the extreme differences between these groups, all are similarly attempting to preserve their beliefs and find roots in the classics. We regard it as the height of civilization, a perfect starting point that we can return to to understand who we are and where we’ve come from. But this way of thinking about the classics involves erasure. Before, during, and after the classical era, humans were making art all over the world, and have continued long since.

In an interview with Sean Illing for Vox, as a response to the question, “Can we ever really stop people from weaponizing history?” Donna Zuckerberg states: “We can provide alternatives, and continue to imagine new and different ways to think about what ancient Greece and Rome mean in the present day.”

This is what many modern authors seem to be doing when retelling classical myths; reframing familiar stories to have a message that they, and others, can better relate to. Whereas many regressive groups, particularly in the online sphere, look to the great classic works to conserve their own ideologies in an unchanging past, others want to transform these familiar stories by emphasizing the different ways they can be translated and interpreted for our time. It’s a mistake to place the classic authors on a pedestal, but also to ignore their problematic histories to glorify the present. Today’s indie lit authors are bringing attention to the process of using myth in modern literature.

The Bringers of Fruit: An Oratorio by Elizabeth Switaj is a retelling of the Persephone myth, one of the more hotly debated myths. This retelling considers the many voices and characters surrounding the myth, reflecting the current interest in the many different versions of this myth. We argue about translations, edits, and misunderstandings that occur, parts of these myths that are omitted or change depending on the storyteller. In the same way, Switaj writes in pieces, poems, and codes. She doesn’t interpret the myth singularly but gives it the many voices of the characters within, in an incredibly holistic telling of the story. While Persephone and Hades are the main focus, we get to see the inner thoughts and reactions of the cast of gods to one another, and how our wants and desires change over time. We even get some voice of a narrator during the intermezzos. The most striking of these is the first, “Intermezzo I: Clearing up the Question of Persephone’s Consent,” which, intentionally, doesn’t clear this question at all but instead highlights it.

Switaj works with an understanding of the fact that we will never know what happened because this is a myth, at the end, and a very old one. We’ll never know just the right translation, or the right interpretation, and to ask someone to ignore the traces of misogyny and violence in this story would be harmful.

Daniela Cascella’s Nothing as We Need It: A Chimera instead relies on our familiarity with the myth in order to discuss a topic or feeling, a yearning as it’s described. An Italian-British author, she explores the space between literature in its native language and in translation, comparing it to the impossible three-part amalgamation of a creature that is the chimera. Almost like Frankenstein, we use the term to refer to something made up of many, ill-fitting and different parts that still somehow function. But as Cascella knows, there’s something different about the Chimera: the associated longing and unfulfilled desire that comes along with its creation. She fills this myth with a desire for communication and literature that, much like the classic works, will never be perfectly translated.

In Love Letter to Who Owns the Heavens, Corey Van Landingham asks us what’s changed? And what stays the same? We know gods and myths, wars and lovers, but what’s different? How have letters and poems evolved over time? Van Landingham bridges the divide between old and new, familiar and not to create her own myths and epic poems in the oh-so-familiar space left by the classics. With drones and sexts in the same poems as great deities and epic wars, the myths created in her poems are current and now, but we can always find that inkling of the stories we’re familiar with. It shows how we’re able to interpret them as readers and writers within our own time.

These indie authors avoid using the classic texts as a mirror for our current ideologies. Instead they use myths as a lens to explore our present. These classic stories are imperfect; that’s what’s so alluring about myth. They leave space for us as readers, artists, and thinkers, and these indie press publications bring attention to the experience of working in the realm of these ancient texts. We cannot control how they’re absorbed by society, and as authors, we’re as powerless to control their interpretations and translations as the classic authors.

Liza Marsala is an intern with Full Stop and and is a senior at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts, where she studies English and Creative Writing and is Co-Editor in Chief of the student literary magazine Spires.

This post may contain affiliate links.