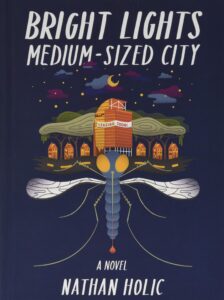

[Burrow Press; 2019]

Free will is an illusion; an early example of this aphorism in practice is in John Milton’s Paradise Lost. The version of god created by Milton sees that his progeny will fall from grace but does nothing to stop it. Creator simultaneously asserts the free will of his subjects and undermines it. If writer is creator, then I’ve always considered the free will adage to be an ironic trademark of one of the rarer forms of storytelling: the Choose Your Own Adventure (CYOA) story. In CYOA, the writer sets the parameters for the reader’s self-determination.

Nathan Holic toys with the role of writer as creator in his book Bright Lights, Medium-Sized City. The first Book of this epic is a CYOA story. Yes, first Book, because like the Old Testament, Bright Lights is a tome split into five Books, with an opener set in a lost paradise to boot. In Holic’s case, the lost paradise is not the Garden of Eden, but instead my home state, its inbred cousin: Florida (think this 1981 cover of Time Magazine.) The novel is set ten years prior to its publishing by Burrow Press, in a 2009 Orlando besieged by the housing market crash. This epoch and setting are not unlike the second line from the Book of Genesis: “And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep.” In the formless void of Florida, Holic, seeks the edges of the state. “Out there, just an hour from the Happiest Place on Earth,” he writes, “is monstrous muck and violent vegetation: there is nowhere on this continent as sinister and darkly magical as the Florida Wild, nowhere so alive and yet so lusty for death.” This line captures the great tension that has always underwritten the Florida experience. It’s also the razor’s edge on which the characters Holic creates walk along.

Holic’s Orlando is serpent rich, including the lizard brain of the book’s protagonist, Marc Turner, “a toxic male and hapless house-flipper.” The character’s narrative arc is not a clean parabola of rise and fall, but rather a flatline lurking the x-axis from a parallel below. Turner’s various over-levered investment properties become worthless and he takes on work as a third-party loan closer. The disillusioning work turns him into a degenerate rambler poet. He spends his time pursuing sexual partners, waxing on Central Florida’s lurid history, and praying for the success of the city’s one hope: the Orlando Magic.

When we first meet Turner, he’s fresh off of a called off engagement with his ex, Shelley, out partying with his best bud Jimmy who’s constantly stepping out on his wife Sandra. At the bar, he runs into an old acquaintance. She expresses an interest in having more conversation with him and offers to buy him a drink. “Her hand on your shoulder, and you have two choices,” Holic writes, and then presents the choices to the reader:

Turn to page 44 to decline her drink.

Turn to page 47 to accept her drink.

Here is a prime example of the illusion of free will in CYOA novels. The reader already knows that Turner will eventually accept the drink, so the choice is really no choice at all. For Turner, or for the reader.

CYOA books are often written in third person, ceding decision making control of the fictional characters to the reader. But Bright Lights is written in the second person POV. In second person, the book becomes more like a role-playing game. “You,” the reader, become the character. I recently read Siân Griffith’s “Taxonomy of the Second Person” in which she invites other writers to an ongoing dialogue about the oft-eschewed second person form of narration. The form, Griffith writes, “offers the power of decision making.” But in my assessment of Holic’s decision to use the POV in a CYOA, I’ve determined that though there is some semblance of power, the greatest power is ultimately held by the author. For this reason, Holic’s choice to write in second person — besides being an extension of a sardonic homage to Jay McInerney’s book of similar title — is the absolute correct choice for a story about the illusion of free will set in an economic recession.

During recessions, like both 2009 and our current one, and especially under the government mandates related to COVID-19, we do not even have the illusion of free will, let alone some autonomy. We sit in lines at the Miami Marlins ballpark, go where the National Guard tells us to, and open up wide for the doctor if we want to survive. The second person perspective of these hardships gives readers at least the illusion of control, which may offer some shelter from the storm. Like McInerney before him, Holic uses his power at times to send the “you” on a hedonistic bender through bars and parties, inviting the reader along for a good time. Holic is like a prison guard handing the condemned a lethal dose of opiates, saying, “Do with these what you will.”

All of the Books of Bright Lights take on different forms. Book I is a CYOA, Book II is a series of guided home tours, and Book III is told as a selection of rules imparted unto Marc Turner by his father. A peculiar thing happens as Book III transitions to Book IV though. Holic places a meta-allusion to both Turner’s origin story and the illusion of free will. In a climactic event, Turner gets into a drunken fight at an Orlando Magic playoff game with a Cleveland Cavs fan. The Cavs fan spits in his face. This is the last rule Turner follows. “And you know that’s a rule, right?” Holic writes, “You. Do. Not. Spit. In. A. Man’s. Face. Not just your father’s rule. That’s every man’s rule.” Turner is descended of men who defend their honor in stupid sports fights. Right before getting knocked out – both literally punched in the face, and figuratively knocked out of Book III so hard that Book IV is called “You Are Not Yourself” – Turner feigns ruminations about rules. “Rules. The Rules. Your father’s rules, the world’s rules, your own rules. Nobody else cares, do they?” It’s too late though. He was always going to get his ass kicked. He never had a choice.

Book V is formatted as an exam, and if I don’t have to take exams, I generally avoid them. Even as a teacher, I feel terrible grading them. Alas, I read through it, and found that almost all of the questions were out of order, answered, or not questions at all. It’s a poetic final portion for a novel that toys with form. Turner spends this final section trying, and failing, to get back with Shelley. Holic places an essay prompt right after this attempt.

Essay Prompt: Given the above scenario, write what you will do and say next. Keep in mind that your response must be written in a way that reflects your aforementioned level of intoxication. Consider drafting the response with your non-dominant hand in order to ensure that the handwriting is sufficiently impacted.

Perhaps use the following question as a means of generating your response: If you were face to face with the ex-fiancé that you desperately wanted to win back, the woman you now realize you’d treated poorly, and you had just this one chance to say something to her before she left town for good . . . . what would you say?

The prompt is replete with a “teacher’s guide” that doesn’t exist, and a grading rubric. The exam is a farce that, coupled with Turner’s inability to change his own narrative, finally breaks all illusions of choice. Even the author, who has been in total control, cannot neatly tie up all of his narrative threads. The entire power structure of the novel: its Creator, protagonist, and readers, like spinning plates, come crashing down. With all illusions broken in the text, I made out to finally truly express my free will, callously fast forwarding to other exam questions or even going back to toy with every single scenario I didn’t pursue in Book I. . Perhaps this chaos, to read a CYOA book completely out of order was my only true expression of autonomy. Either that or the chaos was somebody else’s design.

Jason Katz is a professor of writing at Florida International University. He is the fiction editor of Gulf Stream Literary Magazine. His essays have appeared or are forthcoming in: the Bitter Southerner, Ploughshares, and the Offing. His fiction debut is forthcoming in Waterproof: An Anthology of Remembrances About Miami.

This post may contain affiliate links.