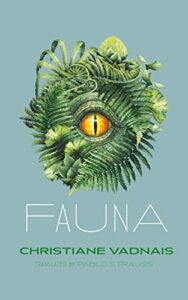

[Coach House Books; 2020]

Tr. from the French by Pablo Strauss

In the West, we tend to think of human-induced climate change as a problem primarily for others. Its most prominent victims are nonhuman landmarks and species and human others such as the lower classes of the Global South. But Canadian author Christiane Vadnais explodes the idea that anyone can insulate themselves from the ecological damage our corporate irresponsibility and consumerist lifestyles have inflicted on the globe. In her startling debut Fauna, a climate-fiction novella exquisitely translated from the French by Pablo Strauss, Vadnais brings climate change home to bourgeois suburban society and to the deepest interiors of the human body. With characters sprouting feathers and growing fins, Fauna asks us to imagine the coming transformations in our environments and our bodies.

Fauna’s natural world is teeming with floods, parasites, and other threats to human life. There is no peace to be found in blue skies and rolling hills, as the skies are “toxic green” and almost all the land has been flooded. Far from finding solace in nature, humans are hunted by species whose prey they’ve extinguished, such as polar bears whose seals followed the ice caps into oblivion. Nature has so totally overthrown human control that humans have become an endangered species.

The ferocity of Fauna’s environment alone does important political work in our age of climate denialism. Collective action on climate change has been hindered by many Western people’s disbelief that nature could actually destroy human civilization (or at least their corner of it). In his brilliant nonfiction book on climate change, The Great Derangement, Amitav Ghosh attributes this disbelief to a long tradition of humans subjugating nature, which makes us believe we control it, and to “the regularity of bourgeois life,” which makes us think that irregularities like extreme climate events are too improbable to occur. “Nature,” writes Ghosh, has “lost the power to evoke that form of terror and awe that was associated with ‘the sublime.’” In our literary fiction, nature serves as the charming backdrop of human narratives rather than the plot driving them. By contrast, Vadnais inspires a fear of nature that replaces our modern ecological arrogance with respect and humility. The matter-of-fact tone amplifies this effect by preventing the reader from construing the surreal events as unreal. By narrating natural destruction in a neutral tone, Fauna models one way that climate-fiction can serve environmentalism.

Yet the book is most interested not in how climate change unfolds alongside humans, but how it unfolds inside them. Vadnais insists that the human body cannot insulate itself from environmental changes, that climate change will necessarily be embodied. Through characters like Thomas, the novella considers how humans might mutate in an increasingly damp climate. Thomas lives in a village entirely “cobbled together” from boats floating over flooded land. The villagers experience not only the psychological burden of “earthsickness” for “the dryland,” but also astounding bodily transformations. They become “the ones with rheumy eyes; the ones whose hips lurch no matter what they do; the ones whose dank toes harbor colonies of fungus.” Thomas himself has developed a fin and patch of scales that “grows larger by the day, increasing Thomas’s likeness to the other lake creatures.” Another character notices that “all the disturbances of the planet seemed to be made flesh in her.” What happens to the environment happens to the human body — there is no more inside and outside.

The permeability of human bodies is further explored in the parasite plot strand. The narrator asks, “If even microbiota were distinct from our organism, on a small enough scale, how could anyone say for sure where their own being stopped and the birds began?” By comparing the parasite-infected humans to “walking corpses or ecosystems on the verge of implosion,” Vadnais paints a striking image of the planet as a walking corpse with humanity as its parasite. We realize that the loathing and disgust she induces for the “pale, slimy” parasites are just as applicable to us. Our parasite status partly explains the permeability of our bodies, for as Vadnais warns, “the fate of the attacker is to die with its host.” We are killing the planetary body we depend on, so why do we expect to live? The parasite image encourages us to think of the earth as our body and care for it accordingly.

Fauna’s embodied climate change dissolves the differences between humans and other animals. The suburban society is first compared to a zoo and gradually increases in wildness as the novel progresses. An exhausted corporate boss tries to ward off depression with her therapist’s breathing exercises, just as only “the occasional breath swelling their throats” indicates that the lions in the zoo are still alive. By the end of the novel, the characters live in trees and forage for food. They have no names and their lives are relayed in the same breath as those of the surrounding deer, rabbits, and ferns. Humans lose their privileged status.

What remains enigmatic is whether we should lament this metamorphosis. Is this really a dystopian story? It is certainly marketed as dystopian, and the book’s other reviewers have used the apocalyptic language of a “nightmare” world and “the end of the world” to describe it. Yet it chronicles not so much the end of the world, as the end of a very specific, rather repugnant humanworld: the zoo of capitalism and the human species as global parasite. A purely dystopian reading ignores Vadnais’s palpable delight in the end of this world. When she says of the flooding rains “there is a peace of sorts at the heart of a downpour so precious and violent,” she invites us to see the violence of nature as “precious” and even “peaceful.” For Vadnais the violence of nature is beautiful: “a new world unfolds, teeming with furies and violence and beauty.”

The appeal of “the end of the world” is not only in aesthetic but also moral and psychological gratification. There is a recurring sense that humans deserve to suffer for what they have done to the planet: “The cold and snow keep pummeling her, as if settling a personal grievance.” With lines like this, nature’s violence becomes not only just but also slightly hilarious in its trivialization of human life. The psychological gratification is also motivated by the suicidality of the characters, most of whom are depressed and driven by escapist fantasies. Yet even though they wish “to throw off . . . sensation altogether” and starve themselves, they remain frightened of death and work to survive. Their ambivalence about death begs the question: is the widespread fear of the apocalypse masking a desire for it? Has the alliance of capitalism and political systems induced a collective suicidality that is unspeakable, and therefore veiled in apocalyptic anxieties? Indeed, is this why the destructiveness of nature is so beautiful to Vadnais and her characters, who fantasize about “brilliant blue” floods wiping out humanity? In Fauna, aesthetic admiration of nature, retributive rage at humanity, and collective suicidality intermingle and welcome the end of our world.

While politically productive, the book’s portrait of humanity is often a caricature. The narrative is largely unable to incorporate warmth and softness into its characters, who are rarely sympathetic and always two-dimensional. Humans are reduced to “primal fears” and “eternal” survival instincts. Vadnais’s preoccupation with “eternal” and “ancient” psychology throughout the novella betrays an essentializing ideology of all nature — including human nature — as fundamentally amoral and ruthlessly self-centered. This description shades into prescription as the narrator repeatedly urges us to “get back to wilder times” of primal instincts: “To dream of a future where our species survives, we must get back to wilder times.” Survival is the only moral good left in Vadnais’s “primal” ecology.

Whether or not readers share this vision of humanity, they can savor the book’s vivid imagination and elegant prose. Strauss’s phenomenal English translation makes Fauna one of the most beautifully written books in contemporary anglophone climate-fiction. In our climate of record-breaking fires and floods from California to China, readers can turn to beautiful speculative fiction like Fauna to explore what transformations lie in store and how we should feel about them.

Anna Kasradze is a culture writer and has also written for the Moscow Times. You can get in touch with her on Twitter @gogolized.

This post may contain affiliate links.