[Sidebrow Books; 2020]

The Japanese film House (1977) tells the story of a young girl named Gorgeous, who cancels her summer vacation plans with her father and future stepmom to visit the countryside home of her maternal aunt. She brings her school friends Prof, Melody, Mac, Kung Fu, Sweet, and Fantasy. Together they enter the lonely aunt’s mansion, and into a psychedelic netherworld of flying heads and gory special effects, so flamboyant in their artifice that it amounts to a gothic Pop Art, in which postwar consumer prosperity and the horrors of the recent past intermesh. The director, Nobuhiko Obayashi, who passed away in April this year, first conceived the characters and plot of House with his pre-teen daughter Chigumi, incorporating her personal fears into the narrative.

After she suffers a spinal injury from a bicycle accident, writer Kim-Anh Schreiber watches House for the first time and, with repeat viewings and reams of online discourse, an obsession quickly develops. She recognizes something not only in House’s phantasmagoric content, but in its equally outlandish forms, like the way Gorgeous, in one scene, exists within a square frame overlaying a still shot, until she leaps, “clicking into” the full frame which then starts moving. For Schreiber this moment encapsulates her desire to place her own memories, sensations, meaningful experiences, in such a way that they too can “click.”

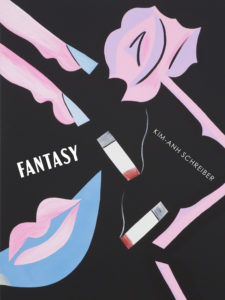

So launched Fantasy, a debut novel by Schreiber, an artist and playwright. It’s a starkly contemporary work that is moving and personal, full of spectacle and surrealism yet never flashy. It unfolds in compact sections, tightly narrated by Schreiber, like protruding narrative vertebrae. And as the sections unfold within the book, culminating in a two-act play, they “click,” regardless of the causal logic, since placing is artificial, and the memories and images called forth easily amount to “unreality and discontinuity.” So Fantasy is an interdisciplinary art novel, a mixture of fiction, memoir, and critical theory, reminiscent of Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha — which also dwells on trauma and language between generations of diasporic women, uses multimedia and experimental forms, and, like Fantasy, incorporates a great film, Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928).

Schreiber draws Obayashi’s movie into her writing in such a way that it works simultaneously as a thematic foil, and as a robust critical interpretation woven through the book’s distinctive parts, as well as, most strikingly, a reflective avenue of communication between generations. If we understand House as a collaboration between father and daughter, we see how each creator conveyed their generation’s fears to the other — the father who grew up in wartime and the daughter who grew up in peacetime. This process is also one of a doubled reflection: two monsters in the mirror as reflections of each person and, “at the same time, a reflection of the other’s monster-and-reflection, as if one generation’s monster pollinates the next generation’s monster like a seed.” If Obayashi was sending a message to the youth tinged by the memory of Hiroshima, Fantasy is a project sent from a daughter to her mother, aunts, and grandmother. Fantasy’s not-too-distant historical determinations lie in the fall of Saigon in 1975 — the grandmother and her children were on the last helicopter out of the city.

Schreiber’s reflections on House are not just personal but stand as an illuminating reading of the film. “House is set in a world of females, about a world of females, generations of females trapped in a house.” The females can be sorted into four categories: (1) Teenagers, (2) Mothers, (3) Wives, and (4) Non-wives. The semantic strangeness of the last type reveals the ideological closure of the narrative: it’s not possible for girls to become single women. Growing up entails passing “through a threshold to another realm,” never to return. To be inducted into the adult world of marriage and history is also to be devoured by it, so that the girls of House end up disaggregated “into body parts, lips, hands, heads, and eyeballs…just anatomy.” The house where the unmarried aunt consumes the unmarried girls who enter it, and the indeterminate, image-saturated house in the climactic final part of Fantasy are identified as “maternal ecologies.” We enter the maternal ecology in order to reject our mother, as Gorgeous in the film and the narrator of Fantasy do.

In the non-linear sections of the book’s third part, “Anatomy of a Critical Incident,” we piece together the narrator’s experience growing up as the daughter of a Vietnamese mother and a German father, with the histories, cultures, and religions of both lines making their claims on her — whether it’s photos and heirlooms from Vietnam, where even the age system is different, or her role as the North Star in the first grade Christmas play in her Catholic school in Pennsylvania. As she seeks to understand this mixed heritage in her childhood, she also moves between her Vietnamese grandmother, called Ba, and her German grandmother, called Omi. She remembers Ba’s house fondly as a cacophonous space, filled with siblings and cousins, “talking and filling the room with laughter and sound.” We learn about her difficult relationship with her narcissistic and absent mother; in the stead of her presence are commodities, like a silk shawl, or the daughter’s imaginings, fantasies meant to fill in space, to match the mother’s “art-directing” of her own image, to create the impression of an “effortless” and “happy ending-ed” life.

“I was a child who appeared emotionless, a grotesque expression of the life she wanted to have, but couldn’t have,” Schrieber writes.

And everything that she didn’t get that she felt she deserved from her life, which she felt had been broken, through bad luck or curse or karma, she impressed onto me: her eternal audience, her dystopic mirror, spinning her out from whatever image she wanted to eat, drink, or inhale of herself in that moment. She always had a way of conjuring in me metaphors of indigestion.

The narrator constitutes her own sense of self on her mother’s reflections of her, and Schreiber describes from the inside the resulting painful contradictions, feelings of control and neglect, emptiness and inadequacy — “I was absolutely intimate with the estrangement.” In a scene in a mall with her mother and aunt, when the daughter resists her mom’s outfit choices for her, it leads to the mother’s outburst. “I’ve sacrificed and sacrificed to give her everything I never had. MY LUCK that I got the bad seed.” Shortly after, she leaves her sister and daughter there at the mall, compulsively leaving the family. The daughter remembers moving on to an empty gemstone pool, and she and her aunt go down to a skating rink, where “we danced in our sneakers, using the ice to slide. Scintillating light glinted across the ice.” But this part is only a vision. Her aunt tells her later they had simply waited in the breezeway for her father to pick her up. She had “totally imagined” the gemstone pool.

In Fantasy these memories are parcelled out among vivid imagery, descriptions of the events in House, and bits of popular media from Dragon Ball Z to The Baby-Sitters Club. Schreiber furnishes this mosaic of images and events for us, allowing us to view her as an artist with a need to make things. And her reflections on the process of piecing these diverse yet undeniably personal elements together make form another concrete process of coming to know oneself. To know yourself, perhaps you have to look back to your past, as Schreiber suggests: “By putting these notes together, cutting, editing, collaging, organizing, and reorganizing, I began to understand the story of what happened.” Without going further into the rich patterns of icons and motifs Schreiber weaves together, this is the fundamental aim of Schreiber’s project, which constantly lays bare its devices in order to share the feelings that seem to explain themselves within the forms, inscribed in the mask’s disfigurements — and disfigured faces recur very consciously in the book, evoking trauma but also an open and self-aware pleasure in fictionality.

The last section of the book is a play called “The Maternal Ecology.” There are still long descriptive passages, and the daughter continues her narration, now as a character in a house that serves as a new setting. Schrieber tells us earlier in the book that Ba’s house is the house of her dreams, and Omi’s house is the house in her heart. Walter Benjamin wrote of the dream house, filled with passageways and furnished with our many desideratums, but with no outside. The setting is a dream house in that sense, onto which the daughter projects scenes with her mother. “This time, I held her captive as a monster in a mirror, where I visited her on my terms. I conjured whole scenes and stories of the two of us together, a movie in my mind.” This is an up-to-date dreamhouse with cameras and innumerable monitors, playing clips of House and other female-centered media from the 70s. It’s also literally broken, falling apart. There is Mother and Daughter and also Grandmother V and Grandmother Z, as well as — another doubling — a mother flower and daughter flower named Karma and Khaos, with sister flowers, living alongside the other characters.

In these scenes Fantasy comes together in every sense of that eponymous word, and the text itself lists off a few of them, including the word’s origin in the Greek word phantos, “visible.” The flower family, with their physicality compared to Mother and Daughter, is part of this business of making-visible. There is an atmosphere of morbid commodities, like a “bee venom face mask,” and a spine like a “bone cello.” Everyone is at least somewhat preoccupied with glamour, and family relations take on the character of money relations. It’s a female space in which the Sisters smoke incessantly, the Grandmothers, surrounded by “rings and auras,” inspect and pinch the Daughter’s breasts. At one point Khaos says, “Ugh, this is so suffocating. So many women, nowhere to go. It all reeks of formaldehyde.”

These scenes consolidate the different relationships Fantasy raises, not only familial, but also “to objects, to beauty, to self,” and the “forms of liberation” that are possible (and possibly damaging). Privacy disappears while the characters’ inner lives are broadcast to an absent public. Everything seems ephemeral except for the body; and yet the properties and pain of a woman’s body are displaced on floral doubles at the same time that the daughter tries to resolve her emotional trauma into her injured body through her creative faculties, her “fantasy.”

Readers may have qualms at first about where the narrative strands and meanings go, or what happens to the historical backdrop of Vietnam as we go deeper into Schrieber’s critical and imaginative construction (it tries to seep into the house in the form of bugs and dirt). Schrieber will not find an explanation for her mother — she can’t “straighten out a crooked story” in order to heal herself and be at home in her body. What we have are the transformations of memories and desires into images that dazzle while carrying an evasive sense of sadness; the dream work of theater.

Fantasy reminds the reader that as we look at the often broken and crooked stories of ourselves, we can’t forget that history keeps circumscribing us, even as its content eludes us. In Fantasy, history’s effects are known through the book’s forms, its strategies for structuring itself — which doesn’t make history less hurtful. Consumer society, with its swarming images and its ability to package even the vaguest feelings of nostalgia into an experience for your purchase, makes it harder to “think history.” It also impacts how we move through our own histories as we try to construct and reconstruct them, how the self helps and also stands in the way of the effort.

Fantasy then is a thoroughly unique reading experience, not only on the surface with its interweaving of memories and visions, of the different and often disjunctive parts of the self, but of the binding ties of these subjective aspects to social history. Just as impeccable as Schreiber’s crystal clear writing and her arrangement of her material is her timing. Obayashi’s death at 82 has revived interest in his work (House was his debut film), and April 30 marked the 45th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. These events speak to the ghostly nature of Schreiber’s book and of our consciousness of the past, equally determined by how we live now and where we came from.

Alex Lanz has published stories, essays, and criticism in magazines including Entropy, Shantih, and Empty Mirror. They live in Brooklyn.

This post may contain affiliate links.