The Nobodies presents the extreme consequences of a typical childhood fantasy—being able to walk in someone else’s shoes for a while. If you follow that fantasy to its furthest limits in the realm of possibility, you get the story of Nina and Jess, two women united and reunited by their power to swap bodies. From this daydream premise, Alanna Schubach crafts the keenly observed story of these women’s lives, from meeting in grade school in the suburbs then reconnecting as adults in the city whose powers were never just fantasies, presenting a bodily exploration of what a lifelong friendship can do to a person. (Something supernatural.)

I had the pleasure of emailing with Alanna about magic, Long Island, and the hazy boundaries of the self.

Kyle Francis Williams: The Nobodies has an essentially fantastic or supernatural premise, in that its two main characters, Nina and Jess, can switch bodies. However, everything surrounding that is almost naturalistic in approach, having a real warts-and-all feeling for the dailiness of these characters. How did you go about striking that balance? Did the two elements together reveal something in one another?

Alanna Schubach: It was important to me that despite their power, Nina and Jess still be subject to all the ordinary rules, particularly those imposed on young women. Their body-swapping ability is specific to only them, and therefore a secret that ties them to each other. They’re a closed system. This felt to me like a way of getting to the heart of the intense bond that can form between young girl friends, and how that bond can make you feel like you have exclusive access to a separate little universe, which is intoxicating, but can also easily wind up dangerous and devastating.

I’ve often found in my writing I naturally turn toward some sort of fantastical device to get at the questions or themes I’m interested in—like I can’t fully explore these ideas without looking at them a bit askance. But what turned out to be an interesting aspect of the process of writing the book was that the fantastical premise of body-swapping, and the realistic elements of the setting and other aspects of daily life, themselves kind of switched. The swapping started to become more matter-of-fact and the supposedly realistic world more strange.

To be able to switch bodies with another person seems to me like a quintessential fantasy or daydream, like attending your own funeral. Why do you think that is?

It’s a little spooky you mention attending your own funeral, because the novel I’m now writing is kind of about that—the main character works for a company that stages fake funerals for people who aren’t actually dead, ostensibly as a means of delivering these not-dead people the ability to take stock of their lives and experience catharsis in a way that’s not ordinarily possible. It would probably be a deeply narcissistic exercise, to actually put on such a ritual for yourself, and also irresistible if it were available.

As for body swapping, it seems to promise a lot of really seductive possibilities—the relief of leaving yourself behind for once, and trying on a wholly different way of moving through and seeing the world, the secrets you might uncover about that person you’ve switched with, the sense of wholly possessing someone you find fascinating or are jealous of or obsessed with. Even with the people we know best, there’s so much of them we can only imagine, so many inner sanctums we can’t breach. Which makes it easy for us to develop mistaken ideas about what animates them, or to become convinced they have something essential that we lack. So I was very interested in questions like—what if you could actually inhabit another person and investigate them and their lives from the inside? Would you find there what you needed? Would you finally feel complete?

I think in both fantasies, body-swapping and attending your own funeral, there’s something quite indulgent. It interests me to explore what would happen if we could indulge some of our darker and more selfish impulses. I suspect in both cases it would not be as fulfilling as we hoped.

I love that I mentioned attending your own funeral. I wish I could call it a premonition. Would you say you’re drawn to everyday fantasies in your writing, and the narrativizing they allow us? Or maybe the fantastical devices bring you to these kinds of fantasies, I suppose it’s kind of chicken or egg. What draws you to the fantastic? Have you always wanted to write toward that?

I think so. My first short story that I wrote as a child was called “Ghosts Who Are My Friends,” one of the titular ghosts being a Holocaust victim. So, very cheery stuff right out of the gate! As a young reader I was drawn to fantastical fiction, and dove into Stephen King’s oeuvre pretty early. I remember reading somewhere that King’s still afraid to go into his basement because he might encounter some malevolent creature lurking there in the dark. Like him, I suppose I’ve held onto certain childlike aspects of myself, fears of the unseen. (I will never look into a mirror at night and say “Bloody Mary” for instance. Why ask for trouble?) I understand these fears to be calls coming from inside the house—coming from me, my own projections. Putting these fantasies into writing is maybe a good way of managing them, and also very freeing. I can use fantastical devices to explore questions that preoccupy me without becoming preachy, or having to offer firm answers. I wrote this short story, for instance, called “The Man Upstairs,” that’s essentially about exploitation of working-class people, except the working-class person in the story is the tooth fairy. I seem to be unable to tackle these themes head-on and instead have to come at them from weird angles.

Could you say more about how the “supposedly real world” became more strange? You have these very nuanced but nonetheless alienating portrayals of place in this book, especially when considering New York City and Long Island. Are these what revealed themselves as strange to you?

Yes! Long Island I found deadly dull as a kid. Just these dense suburbs, people packed on top of each other with nothing to do. The city is so close but feels unattainable. And many Long Islanders don’t ever go there, despite taking pride in their proximity to it! I always knew I wanted to write, but as a young person I felt that my place of origin left me with no material. Of course in leaving I began to discover what was unusual, and indeed strange about it—the island’s stark racial and class divisions, its geographical oddities, the particular slang and rhythms of people’s speech, the haunted feeling of the beach at night, etc.

My time in the city has overlapped with these successive disasters—9/11, the financial crisis, Hurricane Sandy, Covid—and I’m fascinated by New York’s continuous reinventions and metamorphoses, and the ways people cope and try to find sense in the aftermath of disaster. A lot of strangeness there.

In both settings the book’s main characters struggle to find some kind of foothold. Part of the struggle is that of course they are truly separate and alone because of their power. But at the same time they’re still young women subject to larger forces beyond their control.

Being that we are both from Long Island and write about it, it was inevitable for me to ask you some questions about it. I should say I think you painted a portrait I find very familiar, by the way. Neither of us live there now; why and how did you find your way back through these pages?

Growing up on Long Island, I couldn’t wait to leave. It did feel alienating to me as an artsy kid. I felt it had nothing to offer and that it was an embarrassing place to come from. Others seemed to think so, too—I remember in college when asked where I was from, “Long Island” would get this inevitable eye roll in response. I think we were seen as brash, oblivious, and somehow provincial despite having lived a stone’s throw from one of the world’s major cities. And there’s truth in that. But once I started writing about Long Island I was awakened to the value of those qualities—like, hey, at least we’re distinctive. At least we stand out. That’s certainly useful when building a world in fiction. And maybe there’s something fun and subversive about being a loud, brash provincial in the face of urban sophisticates. I’ve come to a place of acceptance and maybe even a little pride about being a Long Islander at heart.

And for the novel, the central premise was so out there I needed to ground it in something familiar, something I could write about with some authority—a place I have strong and contradictory feelings about. As a kid, Long Island values felt to me very grounded in the material—a lot of emphasis placed on your home, your car, your stuff, etc. and also on being a savvy person with both feet firmly on the ground, someone who couldn’t be screwed over. So it was fun to write about something so immaterial happening there—about girls floating out of their own bodies and becoming obsessed with the supernatural, with psychic powers, with the dream realm.

I’d like to ask you a structural question, because I am always curious about how writers structure their work. This book is told in chapters that alternate between the girls’ childhoods and then adulthoods, after they are reunited. I also noticed that the book is kind of episodic in the way that things happen. How did you arrive at this structure?

Maybe it’s a sign I watch too much television? Only sort of kidding—in addition to that, there were several reasons for the non-linear, episodic structure. One is that I did write the book out of order. I actually started with a chapter that ultimately ends up coming toward the end, when Nina and Jess are in high school. That was the episode that came to me first, that time in their friendship that precedes a major rupture.

Then I went back to their childhood and began to figure out how they got to that later point. I did write chronologically for a while, but then found myself jumping around in time. I’ve seen this described by Matt Bell as “writing the islands,” that is, “writing the parts of the story you can see and then connecting them later.” I’m a firm believer in going where the energy and excitement is in a first draft, especially for a project as massive as a novel. Otherwise it can quickly start to feel like a slog, especially if you believe there is all this material you “have to” get through in order to reach the bits that excite you. I ended up eliminating or never writing some of what might have been that interstitial, less critical material, the quieter, in-between periods when things are going pretty smoothly between the women.

I remember my father once gave me advice about relationships when I was at a difficult point in one—he said a long relationship is like a human life, in that it goes through many distinct phases, just as a person does in their development. The book ended up feeling like a portrait of these phases for Jess and Nina.

As for jumping around in time, initially I did start off the draft with the first childhood section (now the second chapter). More than one early reader argued that it gave the wrong impression—it had more of a YA feel, made the stakes feel lower, took too long to reveal Nina and Jess’s power to the reader. That rang true to me. When I started instead with this glimpse of the two reuniting—and switching bodies again—after a long separation, it felt more dynamic and raised more questions. I found I liked the tension generated by nonlinear structure. The suspense stems not as much from what will happen next but why things have already happened the way they have.

As well, the book is entirely from Nina’s point of view, which I found really interesting as a driving tension and a structural choice. What were you thinking about when you made that choice? Were there previous drafts that have Jess’s point of view as well, or was our limit to Nina always a part of the book?

I never wrote from Jess’s point of view. I wanted her, despite their extraordinary level of intimacy with each other, to be confounding to Nina (as Nina presumably is to her). And I wanted Jess to shock the reader, too, though at the same time, part of what I so enjoy about writing in the third person is the space between the narrator and the main characters, and how in that space the reader can perceive things that the characters fail to perceive about themselves and each other. That feeling of knowing and seeing more than the main character when I’m reading is thrilling. It makes me feel like more of a participant in the story. So my hope is that the reader understands some of the things Jess does, sees their cause and effect, even when Nina doesn’t. I wanted to get at the blind spots we have about each other and ourselves. And how dismaying it can be when a person we thought we knew so well does something we couldn’t have predicted—is totally out of what we believe to be “their character.” Because who we think other people are is really just our versions or projections of them—our conjurations, Philip Roth wrote in The Counterlife, which I read recently and thought was genius. It’s troubling but also, I think, exciting that people will always be capable of surprising you.

One of the things I was most compelled by, in the body-swapping, was the way Nina feels that nothing in her life is truly hers, shared and at times orchestrated as it is by Jess. The boundaries of “selfhood,” whatever that is, are really tested by this novel, lending a much more literal sense to the concept of dissociation. Were the concepts and questions of selfhood something you went into the novel with, or did they expand from the material?

The novel Sula by Toni Morrison was one that influenced me a lot for its depiction of female friendship. There’s this really haunting moment in it early on, when the main character, Nel, is a child. After she returns from her first journey out of her hometown, she looks into the mirror and has this epiphany:

“I’m me,” she whispered. “Me.”

Nel didn’t know quite what she meant, but on the other hand she knew exactly what she meant.

“I’m me. I’m not their daughter. I’m not Nel. I’m me. Me.”

Every time she said the word me there was a gathering in her like power, like joy, like fear.

I can remember experiencing a similar sensation as a child, this feeling of, I’m in here, and there being a power to understanding that. But what is the I and the here? Is there any real constancy to either? That was definitely something I thought about heading into my own novel, and once I started writing, the pleasures and pains of allowing someone else into that here, close to that I, arose naturally. We want to be seen deeply, or at least we think we want to, and Jess sees Nina better than anyone else. (But of course not completely—even with their power they have massive blind spots about each other and themselves.) And Nina finds that allowing someone in and being seen like that makes her feel like she’s losing ownership of her life and self. Virginia Woolf wrote this about being ill but I think it applies: ”Always to have sympathy, always to be accompanied, always to be understood would be intolerable.”

And at the same time, another of the more distressing aspects of body-swapping for Nina is that no one else notices when it’s happening. Even her own mother doesn’t realize when Nina is not Nina. So that brings up questions of: Does anyone recognize me or know me at all? And who am I apart from other people’s impressions of me?

Especially toward the end of the book, some pretty heavy and tense situations arise that have to do with consent and bodily autonomy—bodily autonomy already being a much more complicated concept in a story where its two principal characters switch bodies. Some of these scenes are maybe the most horrific in the book, thinking about the body horror of body swapping—the body horror in this book, concerning puberty and also the supernatural being extremely well done, by the way.

We’ve talked a bit about the questions of selfhood with regard to the body swapping, but not how those bodies act in relationships with others. What were you thinking with regards to the concepts of bodily autonomy and consent in this book?

I’ve long been really interested in body horror. I love David Cronenberg’s films (and actually wrote a review of his first novel for Full Stop many years ago!) It always seems strange to me that more women aren’t into him, because who understands the horror of bodily changes better than we do?

Going through puberty is maybe the first real experience of body horror, apart from the weird injuries you might sustain as a child. I have such a clear memory of being catcalled for the first time, when I was out walking with a group of girl friends. We were in sixth grade. A car of guys drove past us, yelling something; I don’t remember what, but I do recall the sense of total confusion, especially when the other girls seemed excited by it, by the fact that the boys thought we were hot. I was like, What? How is this something we want? I still played with dolls.

But at that age your body might already be developing, and suddenly you’re supposed to be accountable for this power you have over boys and men, one you didn’t ask for and have no clue how to wield. Which is very much like Nina and Jess’s power when they first stumble upon it. They’ve been granted this ability—by whom, though? And what should they do with it? What are the rules, if any, for its deployment?

I was also exploring, with the girls’ power, the idea of access. Nina has a realization at one point that once she gives a boy permission to do certain things with her, she can’t take it back, or at least she feels she can’t take it back. And so it is with Jess and body-swapping, too. It’s well-covered territory, how women are socialized to prioritize men’s comfort over their own. I wanted to get into how girls are capable of sexually humiliating or even violating each other, too. A lot of that may be internalized misogyny, but I think part of giving female characters their full humanity on the page includes letting them be ugly and dangerous and selfish in their behavior, wherever it might stem from. I wanted to look at these ambiguous zones of granting a person a certain amount of access to yourself and your body, but then having second thoughts about it, or not liking what comes of it, or wanting to establish limits when it feels like maybe it’s too late to do so. Those moments when it seems like a troubling boundary-crossing has occurred, but it’s not completely clear who to blame.

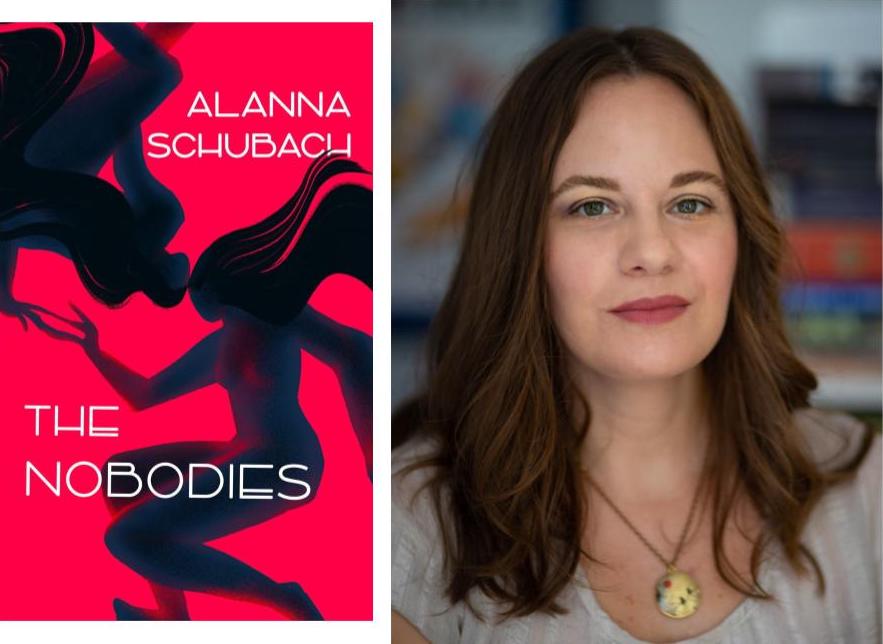

Alanna Schubach is the author of The Nobodies (Blackstone, 2022). Her short fiction has appeared in Shenandoah, the Sewanee Review, the Massachusetts Review, Electric Literature, and more. She was an Emerging Writer Fellow with The Center for Fiction, a Fellow in Fiction with the New York Foundation for the Arts, and a MacDowell fellow. She earned an MFA in fiction from Sarah Lawrence College. Follow her on Twitter @alannaschubach.

Kyle Francis Williams is a writer living in Brooklyn. He is an MFA Candidate at UT Austin’s Michener Center and Interviews Editor for Full Stop. His fiction has appeared in A Public Space, Southern Humanities Review, and Epiphany, and is forthcoming from Southampton Review and Joyland. He is on Twitter @kylefwill.

This post may contain affiliate links.