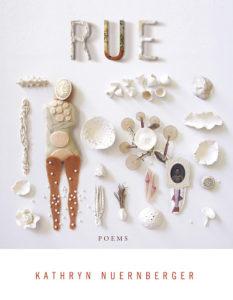

[BOA Editions; 2020]

There are two kinds of poems in Kathryn Nuernberger’s latest collection of poetry, Rue. The first is an intensely confessional mode. The second is a kind of historicist cataloguing of the fruits of research into herbal remedies and early ecologists. In the former, the poems chronicle a kind of torment, marital discontent, sexual longings, a political mismatch between speaker and setting, motherhood, and an unforgiving accession into female middle age. Paired with an associative, variously prosopopoeiatic series of meditations on the natural world and European encounters with it, what Rue shows, beyond its cathartic work, is that even under adverse conditions, Nuernberger’s drive for knowledge of both self and world cannot be extinguished. (Like a fact from one of Nuernberger’s poems, “prosopeia,” a nearby word much easier on the eyes, is also the genus of shining parrots).

It makes sense that Rue has already garnered a number of full-throated, supportive reviews. It is an interesting book. The poems read as conversational, immediate, as if your very smart and very unhappy friend is writing you regular (indeed, unusually beautiful) emails, relaying the day’s archival felicities, the luminous kernels of theories of what and why things are. You feel for her, so precisely winnowing out the many invisible ethical calamities she encounters or perpetuates in a day’s activities or thinking. And what, when so many of the available levers for justice have been found to be broken, damaged, or corrupted, can she, or you, do? Having lived with the knowledge of having nothing, or no one, to appeal to — perhaps only the space of poetry itself — Nuernberger’s confessional poems in this collection voice the daily indignities, the silent and silencing structural contortions, which accrue to an unbearable pain, within the parameters of a white, upper-middle-class life. Nuernberger pitches across the barrier of what might be considered inconsequential, or ignored — in life, and in poetry — aerating particular consequences in a kind of torrential disaffection, hewn together in poems that largely conform to a mid-length line accruing into long, but usually adroit, single stanzas. It is a formula, dependable like an L.L. Bean tote bag, into which a wide variety of curiosities, divergent feelings, anecdotes and observations can all be safely portaged.

What holds Rue together is not just its diaristic, personal nature, though that is one of its chief readerly pleasures. Its through-line is another iteration of personal consideration: how might the speaker and others like her, in a historical moment of intensely public social reckonings, incorporate the lessons and methods of a progressive moral paradigm into daily life? The scope of personal responsibility, both in the world and in a poem, has never been larger, or more critical to understand. And by making public these processes, differentiated only by worsening degrees like a fever, Nuernberger puts this confessional mode to a more useful political purpose.

The work of Rue’s confessional poems is not only to process transgressive longings (“I confess, I was looking him up and down / like a woman who had been reading Rumi and also a tome / of bear cults in Europe”), stage effective arguments (“Because it is not unreasonable for a woman / to think she has a responsibility to address / men crossing boundaries shamelessly”), or fight for authenticity at its barest (“’You’re doing a great job being /professionally objective, but doesn’t it ever just piss you off?’”). Its project is something larger, perhaps more tenuous: to connect contemporary progressivism’s lessons to ordinary public settings, where these lessons most often reverberate. From the resolute irresolvability of the academic department, a stolid office life, the glimpses afforded of others at the library, to the loosely ignored, perhaps constant, transgressions of a coffee shop, to the indeterminacy of a public playground, the physical places and contemporary moment of these confessional poems occur in a rural red-state setting mostly hostile to such social innovations where Nuernberger’s speaker tries her utmost to sort through the implications within everyday situations. In a prize moment of social critique at the end of “I Want To Learn How,” a long poem that ironically rehearses the limited possible responses in patronizing terms of “nice = ” and “mean =” to a former cop in a small town who suggestively touches the speaker’s back, Nuernberger’s speaker calls out her male friends who have failed her:

What I do = I see these men who

have been friends of mine trying to arrange

their sad faces because they like to think

they themselves are feminists.

They’d tell a man not to touch them

in a heartbeat, they think, if it ever happened

to them. They’d tell Glen not to

touch me, if that’s what I’m asking for.

If I were mean enough to decide

I really wanted us to understand

and know each other, as true friends do,

I don’t know what I would say.

I might say all this. And then

they might say there are other words

besides nice and mean. They might say

there are other definitions. Perhaps they

will tell them to me, if I give them a reason.

Or perhaps they will walk away and we will

never speak of it again, as usually happens.

Encountering such electric frustration is moving, and sad. But these poems are undertaking, undergoing a personal reckoning made public, which is what the confessional mode offers at its best. In line with Sianne Ngai’s framework for Ugly Feelings, these poems display their emotions “as unusually knotted or condensed ‘interpretations of predicaments’ — that is, signs that not only render visible different registers of problem (formal, ideological, sociohistorical) but conjoin these problems in a distinctive manner.” The most consistent predicament is, in a phrase, life under patriarchy, and its main vehicle is assault, from the gesture of a hand moving down the speaker’s back to the recollection of a medical assault. Indeed, the most acute admission of Rue is its claim of assault “by an OBGYN in his office in Logan, OH / and I’m willing to testify to that.” Its tragic savvy is to disclaim its own testimony in the lines just before, “. . .but I’m not so naïvely idealistic as to think / any good could come out of saying to the public that. . .” And yet, the latter is also the public statement, hoping beyond a rightful cynicism that this admission might change something, anything. Inclusion of direct violence to the speaker shifts the tenor of the book beyond the occasionally ornamental drama that haunts the confessional, and pivots instead to its historical moment in which #metoo has made space for, at the least, a public catalogue of assault, after assault, after assault with no end in sight.

Nuernberger’s declarative titles announce their interpersonal objectives, especially in the early poems of the collection: “I’m Worried About You in the Only Language I Know How,” “I’ll Show You Mine If You Show Me Yours,” “I Want to Learn How,” or “I Want To Know You All.” The scenes comprising each portray a speaker at some distance, or in disconnect, from the world around her. She’s critically self-aware, a blessing and a curse which is occasionally funny, as in “The Petty Politics of the Thing,” after an extended prosopopoeia attributing both assertive and withdrawing tendencies of the speaker to recognizably suburban animals:

Sometimes in the course of a day I hear

the cat-rabbit in the back of my mind whisper,

“I will fuck you up.” Oh, I love her, I love her

for how real she is. She can see through

even the most tangled bramble of rhetoric.

Most often, the speaker’s profound, rural isolation “two hours away from anyone who likes me” propels her into admission, confession, analysis, or interrogation, as if rhetorical positioning will assist her in this work of attending to the unmet needs of self. But place isn’t entirely to blame, as anyone with left-of-center politics in a Republican state would also attest. I wondered, at certain points in reading Rue, if there would be some consideration of the nature of deeply rural life, as in the astonishing opening trio of short essays in the eponymous section of Nuernberger’s 2017 Brief Interviews with the Romantic Past. But I can see the compromise, indeed, the pleasure in rejecting that kind of miasmic atmosphere, in favor of the pure sound of voice and its power to testify, sort, sift, and assign.

This is the challenge of the essay-poem. At her most musical, Nuernberger channels the propulsive lyricism of Brigit Pegeen Kelly, fulsomely and covertly litigating the failures of American suburban-to-rural life; other patches sometimes don’t fully flower, relying on the work of information itself to sustain momentum. Perhaps when that information is unaltered in the service of testimony, as with Reznikoff’s verse or Maggie Nelson’s Jane, we can see the rhetorical efficacy of a flat tone, of a history book’s plain fact. In their connection between public and private feeling, in the fictive substrate of suburbia each book creates and their urgent political messages, it seems to me that Rue and Robyn Schiff’s A Woman of Property are distantly related, but have not met in person. Particularly in Nuernberger’s “A Natural History of Columbine,” I wondered if its prosopopoeia here, ascribing a woman’s characteristics to a flower, was ultimately at odds with its additional rhetorical maneuvering: incorporating a history of experimental theater based on figures named Columbine, which itself nests a list of domestic violence, which was, in the end, what only seemed like the poem’s original purpose. It is only in the final stanza where I hear the echo of what the poem might have done all along:

Lobsters can’t talk either, though they can clap

after a fashion, so long as they have not

been rubber-banded and their clacking

is not lost beneath the roar of those crashing

waves. The meaning of their pantomime

is impenetrable and will come to replace

clowns and maidens as archetypal figures

at the center of the Theater of the Absurd,

which is a kind of ballet and a kind of circus

that amuses the intelligentsia until it is

supplanted in another generation by

Artaud’s theories of the Art of Cruelty

when we watch a man shave his own eyeball

on the screen while dipping ourselves and others

in a rich butter sauce, with no idea how

it makes more sense than any of the gestures

that came before. Our mother, the flower,

our father, the joke, these are the stories we tell

our children over this glass of sparkling

white wine, letting them watch each little

bubble rise to the surface and pop, because,

as usual, we are at a loss for words as to why

we made some choices but not others, gave

ourselves over to this clown but not that one.

Such a flight of information seems to offhandedly careen, never mind why lobsters, or that we move from that conceit back to the original, exhaust it, and land somewhere in parenting, finally uncertain, having arrived at a stunned silence only possible after summoning a great deal of effort, intelligence, and research. Nuernberger’s second, informational mode, which gradually takes over the book, is almost entirely reliant on captivating details assembled in a loosely humanist panoply including: insects, medicinal plants, selected art, scientists, historical incidents, and sex itself. Fact, and the fact that desire itself bursts and wanes, are in the end Rue’s true subjects.

Fact’s affective resonance shines at its sparest in “Pennyroyal”, unusual in its single-line anaphoric form, which occurs only twice more over the book’s thirty-one poems (and to thrilling effect). “Pennyroyal” uses much of the same energy pinning together Nuernberger’s columbine, but here its facts are revelations, radiating details of its medicinal use alongside other historical and personal trivia:

Pennyroyal, called Lurk-in-the-Dark.

Pennyroyal, “It creepeth much” and “groweth much.” It comes into blossom “without / any setting.”

Pennyroyal, Pliny couldn’t help himself going on at length.

Pennyroyal, creeping on my field for years.

Pennyroyal, before I knew what an old witch you really are, I brought you home to be a bouquet for my mother.

Pennyroyal, drunk with wine for venomous bites.

Further, pennyroyal can “relieve upset stomach,” “reduce flatulence”, is an “active agent pulegone,” can “abort the thing.” But in its wealth of uses, Nuernberger identifies a resonant ambiguity: “Sometimes we’re efficacious. Sometimes we don’t know what we’re for.”

Neither, really, did the early European naturalists, scientists, or historical figures Nuernberger includes in the latter half of Rue know precisely to what ends their work, or their words, would be put to in posterity. It’s not often a sunny afterlife. But of Carl Linnaeus, for example, Nuernberger implores us: “I need you to love him too.” The poem, “Whale Mouse,” outlines his achievements, the tenderness of his thinking, his “sweet jokes”’ — Mus musculus, or little mouse, is the scientific name for the blue whale. Nuernberger’s speaker swoons inLinnaeus’ appreciation for detail. And in a responsible gesture — lest the ode end in only charms — Nuernberger includes the fact, and the language, of how Linnaeus also first classified humans by skin color. The speaker hopes for “a better historian than I” to explain this rupture, claiming to do so would “break the mind of my heart.” Deferring to the reader, in this case, doesn’t feel entirely neutral, instead appearing as a kind of dare to cancel Linnaeus: “What do you / think? Can we love him anyway? Did we / even love him in the first place?” I did wonder, when so much work in Rue is levied toward unseating patriarchy, if there would be further work to disavow white Western patriarchal knowledge systems, too. Instead, we get histories that don’t, at the very least, omit the glaring problems inherent to the lives and work of figures who might otherwise be of interest, such as the first female ecologist and entomologist, Maria Sybilla Merian, noted as such for her watercolors which featured “insects on their host /plants,” and in consequence, “discovered metamorphosis.” This poem, “Bird of Paradise”, also includes Merian’s own violent language to describe colonial horrors on a plantation in Suriname. From that point, the historical-poetic investigation becomes a testing ground for contemporary ethical responses. The poem moves toward the admission — a kind of confession by proxy — that Merian salvaged her knowledge of medicinal plants from the indigenous people of Suriname. The poem tries to think through its predicament in reasonable terms:

. . .There is a point

at which giving so much benefit of the doubt becomes

another exploitation and the conditional tense

just a grammar for the naïve and lying. Maria Sybilla

Merian was many things. . .

Defaulting to the position of human complexity alongside complicity, however true, feels as though Nuernberger is pulling a punch, perhaps under the conviction that study of the past might continue to track towards restorative truth. Here, when the speaker asks “why” such violence could be, “[t]here is an answer that is a silence that grows / longer and deeper as you peer into it.” The poem ends with an attempted restorative gesture — the speaker imagines a woman, holding out a flower.

I don’t know this woman. I have tried to imagine

her. I have tried to imagine being her. To be human

after all, is to look at each other and imagine how

it would be. But then again, maybe we are not

so capable of everything we imagine ourselves to be.

Not knowing, while entirely common, might no longer be a responsible basis from which creative work can be undertaken. No doubt Nuernberger is aware of this, as such circumspection recurs, like a lodestar, throughout the collection. Indeed, the pre-twentieth century thinkers of Rue, even Ruskin and Rousseau, serve as avatars for experimentation itself, (prosopopoeia persisting even here) where the poems themselves can’t, or don’t, quite bend. Yet in one important moment, the form does shift from the essayistic to the single line, allowing such lightning bolts of thought, as it draws to a close, in a powerful apotheosis:

My ire at the kingdom.

My ire at the kings.

My ire at the philosophers who think

they can just reinvent the world

inside the eye of their own minds.

What I want I want on terms as I dictate them.

My ire at my terms.

My ire at my impossible wanting.

These lines crystallize the emotional and intellectual work of Rue. The formal techniques of the essay-poem, distinct as it is from prose, limit somewhat the available methods for presentation of information. Most often, associations and digressions between self and research structure the volume of fact, detail, feeling, and knowledge these poems carry. Moments like this suggest to me that there’s yet an entire lexicon available formed of the fragment, if treated with rigor and a naturalist’s notice and precision, and Nuernberger’s characteristic drive for knowledge that would push the speaker beyond such “impossible wanting.”

But knowledge itself, even the most difficult of truths, supports the collection’s fraught later moments — speakers consider the brink of infidelity, the bedside of a dying father, turning away from a husband, imagine an abortion that didn’t take place. If there’s any aesthetic reconciliation, it is in not quite a merging, but a co-presence of those two poetic modes towards a more relaxed poem, realized in the aptly titled “The Real Thing,” (also a little joke) which, after so much time spent considering so many real things, transhistorical and interpersonal, actually allows for worry, contentment, rest, and the seductive, delighting fiction of the Vegetable Lamb of Tartary. It’s umbilical, hyper-natural, a little bit incorrect, just this speaker’s style: “I like the defiance of plants. They are / at odds with themselves — they do one thing /and also do its exact opposite.”

Alicia Wright is originally from Georgia, received fellowships from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and her poetry appears or is forthcoming in Ecotone, The Paris Review, jubilat, and West Branch, among others. She is a PhD candidate in English & Literary Arts at the University of Denver, where for Denver Quarterly she has served as Conversations Editor, Poetry Editor, and will begin her tenure as the 2020—2021 Denver Quarterly Editorial Fellow (Associate Editor) this summer. Her website is jaliciawright.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.