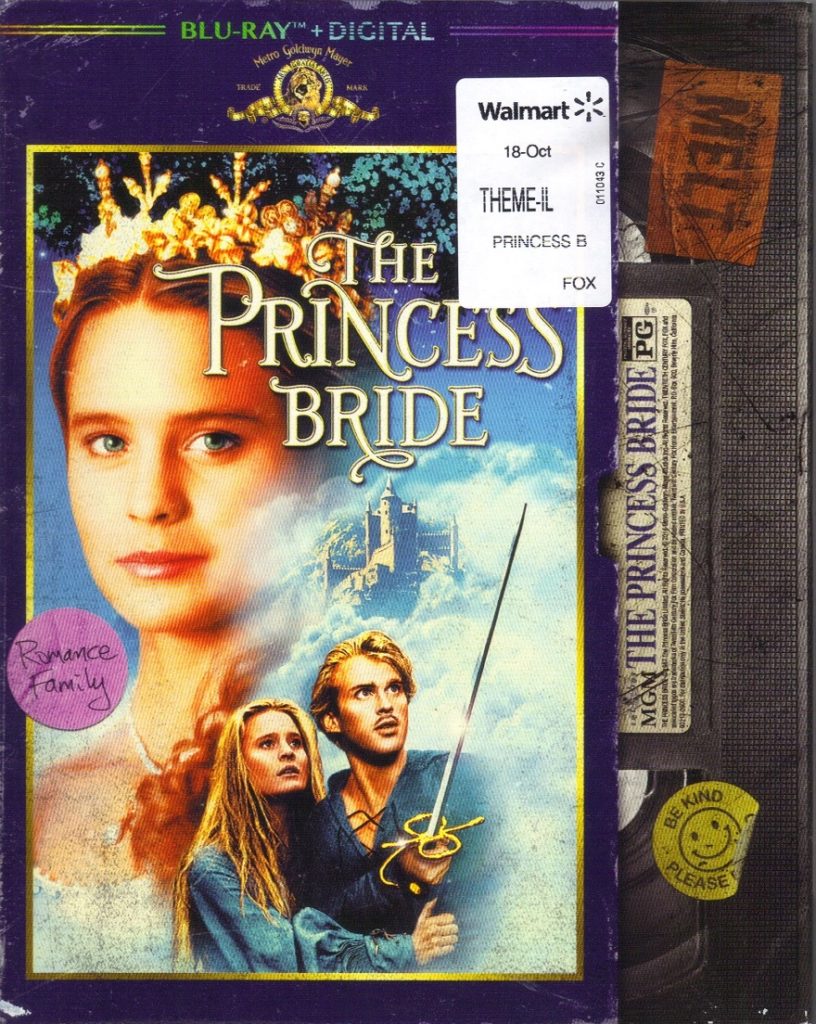

Growing up as the daughter of two writers who pretty much worked with and in every kind of media imaginable, including film, television, and books, my childhood was one big Easter Egg reference. From the time I could talk, I loved stories of all kinds; I gorged on Roald Dahl and Erin Hunter books like they were going out of style, I parked in front of our small, white second-hand tv with VHS tapes of 90s’ classics like The Princess Bride, and Mel Brooks and Monty Python movies on endlessly as my brother and I played in the background, I mashed the buttons of my favorite Gameboy games until I got carpal tunnel and teared up at their plot twists. My family today is still so engrossed in the world of media that we have entire conversations in Frasier quotes alone. These works I love played a huge role in developing the person I am today. They are the inside jokes I make with my friends, the role models whose characters I was inspired by and saw myself in, and the stories through which I related to my world.

And while my case might be a little more on the extreme side, how many of us can say differently? Almost everyone has a favorite book or movie or game that they connect back to on a personal level. This is why we have countless Buzzfeed-esque, “which character are you” quizzes or spend hours arguing on forums about tv show episodes or even inscribing their images onto our bodies. These works are not just entertainment but expressions of our identities and our society. They are a lens through which we try to apply our experiences individually.

Several books from this year’s indie catalogs seek to capture this phenomenon, the way popular culture shapes identities and experiences of the world. Exemplifying this trend is the movie-twined autobiographical Fantasy by Kim-Anh Schreiber, the alternative history of a chef in Dreams of Being by Michael J. Seidlinger, and the Pokemon-inspired po(k)etry of Marlin M. Jenkins’ Capable Monsters. Each tells their stories through other stories, playing with media that deeply permeates the lives of the authors, and thus exploring how the media we love can represent larger themes, issues, and aspects of identity.

For example, in Capable Monsters, “to make space for the validity of oft-dismissed subject material, Marlin M. Jenkins asserts the symbolic, thematic, and narrative richness of the world of Pokémon. His poems use Pokémon as a way to explore cataloguing, childhood, race, queerness, violence, and the messiness of being a human in a world of humans.” As a worldwide phenomenon, many people have been exposed to Pokémon having grown up with it, played the games, or just otherwise become aware of its characters. In relating to the series’ gameplay of categorizing the titular creatures, the author is able to draw parallels to the ways in which humans are labelled in society. He builds bridges between the nature of many of these widely familiar characters to how humans are treated themselves; for example, in the poem “Pokedex Entry 778: Mimikyu,” he draws connections between the mask-wearing “Mimikyu” to the “masks” people wear to avoid marginalization. While it might seem unconventional to some to base a series of poetry off of a video game, grounding the work in the world of this widely beloved series allows Jenkins to be able to richly tackle a diverse range of topics through a widely familiar means.

While not as many may be as familiar with the Japanese horror film House, in Kim-Anh Schreiber’s semi-autobiographical novel Fantasy the author’s association with the film similarly serves as a framing device for the whole book. Fantasy is named for one of the characters in the film, the last girl standing after all her friends are consumed by a haunted building. Through Fantasy, Schreiber is able to depict her complicated ties to her maternal side of the family and the way many of her female relatives have been alternately devoured by her family’s desires, and yet at the same time reverent to them. Like Fantasy and the other girls who are eaten by the house (which in turn hosts the spirit of Gorgeous’ aunt whose fiancé was killed in WWII), Schreiber is caught by the bitterness of her mother and grandmother’s wishes: the disfunction her mother inflicted on her by leaving her life and her grandmother’s hopes for her family to carry on their Vietnamese heritage. Additionally, the genre-defying nature of House, as a non-traditional horror movie, and its depiction of the interaction of the real and unreal, further connects to how Schreiber finds herself expressing her life story. As she notes of her experience watching a bizarre scene where Fantasy takes a photo of Gorgeous, “this is what I want for my memories. I felt that in watching House, in watching its unreality and discontinuity, I was seeing something fundamentally true. Something my spine remembered. But what?” In establishing the analogy between the life of the author and the film, in binding them to House, Schreiber can speak to how blending fiction and reality can express truths about our own experiences.

Even documentary films, which themselves reflect other stories through telling of real history, can invoke further tales. Drawn from the documentary film Jiro Dreams of Sushi, Michael J. Seidlinger’s book Dreams of Being puts a spin on the story, depicting the renowned sushi chef Jiro Ono as if he had been working as an unknown in a franchise Japanese cuisine restaurant. After encountering a struggling writer who becomes fascinated by him and pretends to be a documentary filmmaker as an excuse to continue to speak with him and create a film about his work, the book is a vivid meditation on the artist’s life, the drive for creativity, and the American Dream. Though Ono in both his fictional portrayal and in life is by no doubt a master of his craft, Dreams of Being reminds us of the chance involved in becoming recognized as an artist, how without an audience the creative is contained and unable to have their art be experienced by others. The relationship between the novel and the documentary serves to illustrate the fight required for one to live for their art when they lack the opportunities (like money, exposure, time, or other blessings) that would allow them to make it their whole life. Through its connections to both the real-life story of Ono and its meta-commentary on the act of creation, in grounding itself in Jiro Dreams of Sushi, Seidlinger is able to examine mastery when it is deferred by lack of recognition.

But why are writers today so drawn to inspiration from other forms of media? While the easiest explanation might be to simply place blame on its encroaching, blaring loud forms (ie. advertising), in a way, haven’t stories been always intermeshed within other texts? From small allusions to derivative works, interactions between media is not new. Even content as old as Dante’s The Divine Comedy have found themselves being paid homage in works as diverse as Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho. A reader would have to look hard to find a book devoid of a single allusion or sign of influence to some other piece. But the scale at which these independent books mingle with their referenced media stands out in its completeness; like a symbiotic relationship, the writers utilize the symbolism invoked by the works they are tied to so deeply that they would not have the same meaning without these references. Many literary scholars have dubbed this idea the concept of intertextuality. These books at their heart rely on these other forms of content to tell their story. The texts themselves start the message, the media they draw their ideas from finishes the image.

Although authors are often depicted locked up in a room with only themselves and some kind of blessing from the “Grand Pooba of Inspiration” responsible for birthing their masterpieces, in reality, much of a writer’s inspiration tends to come from other media. In almost every writing workshop or class I’ve been a part of, you could make a drinking game out of the number of times that you get recommended to read more books. As other forms of media continue to gain recognition as art, they also become sources of ideas and inspiration. I remember one fall in my high school days a visiting author was asked what her best advice was to be a better writer. She immediately answered, “play more video games.” There are countless articles too that suggest that aspiring writers dissect everything from the characters to the plots of movies and tv shows to learn from those that came before them.

And even when some may argue that the heavy seepage of other texts into the world of literature might be viewed as “gimmicky,” I would argue that such inside jokes are effective for a reason. Humans are storytellers; pop culture at its heart the newest incarnation of the tales and fables passed around the campfire and before the crowds of eager listeners that our ancestors told. The listeners go on to echo and reverberate these stories, sometimes being retold in an entirely fresh way or other times branching off from the inspiration that they spark. The images we see from other media become a part of a language that is deep and intimate. By linking arms with other media, these writers are sharing what stories they identify through which they can express their ideas.

But beyond finding fuel for creating new stories, maybe in this day and age, we find ourselves coming back to the media that we love because we are looking for a connection to works that provide us with a way to be understood. In seeing ourselves in the media, we bind our souls to countless other people who relate to the same things they see themselves in. Through this, we can find ways to communicate across barriers such as differing backgrounds or borders. The world steadily grows more globalized by the day, but when we read a book, watch a film, play a video, and so on, and go “same,” we are sharing the experience with others who we may now be able to further identity with as well. In utilizing the language of other media within their books, these indie authors remind us that we’re not the only ones out there.

Jacqueline Gamache is a recent graduate of Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts where she studied Creative Writing as an English/Communications major. She has been published in and has served on the staff of Spires Literary Journal at MCLA and is currently working on her first novel. She lives in North Adams, MA.

This post may contain affiliate links.