[Ohio State University Press/Mad Creek Books; 2019]

Readers of Susannah Nevison’s poetry collection, Lethal Theater, winner of the Charles B. Wheeler Poetry Prize offered through Ohio State University’s The Journal, will begin to get the sense that the way we’ve talked about poetry’s musicality and, even more so, the way we’ve understood the capacity for recurring motifs to give longer texts a sense of cohesion — that we’ve been approaching and discussing these elements of poetry in superficial ways. We teach alliteration and assonance, accentual-syllabic meter, and recurring imagery to young poets because these are easy doors through which they can begin to enter the complex world of poetry; but sometimes we stop there, and so a poem or a poetry collection can do nothing more than repeat a melodic figure that we understand is meant to signify spring or the Holy Grail or Darth Vader. 18th-century stuff. The greater available complexities that Lethal Theater reminds us of is more akin to — I’m so sorry — composer Johannes Brahms’s technique of continuous development, here described by another writer struggling to put it into words, Thomas Mann:

With [Brahms], music disposes of all conventional flourishes, formulas, and tags and in each moment, so to speak, creates the unity of the work anew, out of freedom. But it is precisely in doing so that freedom becomes the principle of a comprehensive economy, which allows music nothing accidental and develops the most extreme diversity out of materials that are always kept identical. Where there is nothing unthematic left, nothing that might not prove it has been derived from a single abiding constant, one can scarcely speak of a free style of composition.

To translate that into less historical, less histrionic terms, the book Lethal Theater is built entirely from the scantest thematic material — cell, eye, rib, cross, lake, “bars lash light” — that is then developed into an infinite world. No material in the book is unrelated to those thematic kernels.

Mann speaks of this style of composition as both a type of freedom and an un-freedom, and it is here that this stylistic approach reinforces the collection’s subject matter, an exploration of capital punishment and the prison system in America, how incarceration is turned into a spectacle at the expense of the humans who are trying to make that of that system a grim home. This home is the starkness of a prison cell, the tedium of a regimented schedule, and a necessary overreliance on one’s memory for entertainment, hence the severity with which Nevison restricts her poetic material and forces herself to build something substantial out of almost nothing. She renders this process explicit in the first poem, “Cell Watch: Strip Cell”: “One man to one small room — you / grant him dominion so that he might / render the room expansive and rich, / his kingdom, stretch his mind / indefinitely.” Any risk of rosy portrayal is countered toward the end of the poem, “You’ll build a room within a room, / another world to hold what’s left / of this one,” conflating prison cell, body, coffin, and stanza (from the Italian word for “room”). Though the material makes an appearance in Lethal Theater, Nevison’s first collection Teratology dealt more explicitly with her personal experiences surrounding disability, and it is through the poem’s final image, the Biblical rib, with all its history of misogyny, as well as through the anatomical meaning of the word “cell” that Nevison entwines the corporeal and the carceral. This conversation is not a trifling one, as we all know that the space between criminal and sick will continue to be an incredibly fraught distinction in our country.

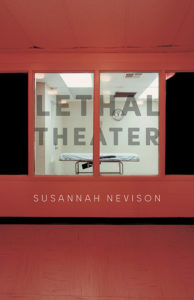

The poet and the project never make the mistake of thinking they speak for the incarcerated or can truly understand their lives. They know, on the contrary, that even poetry is part of the spectacle, part of the “theater” — the beautifully musical title is, on the cover, located within the lethal injection chamber, and we as viewers are outside the room, but about to enter, as we open the book — and it is through their own implication that they prevent readers the comfort of being uninvolved.

It’s the COVID-19 quarantine that has finally given me the time to write about this book, and of course this is not the same as being incarcerated. We don’t know, but we know better. Two realizations that have come out of this situation are the much higher number of prison beds that exist in this country versus ICU beds and the increased vulnerability during contagious pandemics of populations who cannot socially distance; combined with the recent boom of for-profit prisons, especially under the current administration, and the lack of commutation for inmates’ decriminalized drug offenses, we understand that our system is out of control. Lethal Theater likewise does not hesitate to compare carcer and cancer: “Inside a cell, / a man beyond recognition replicates / an old domestic rite, something tender,” and “Watch the sprawl of bodies before you, the tower an eye / you occupy, a gaze that burns their backs as they bend / before you, performing their tasks, labor that divides / and multiplies like the cells in a hive.”

Carcer is not only prison in Latin but the name for the stalls at the beginning of the racecourse in the Roman circus that limit the movements of a horse or a human. And Lethal Theater is about more than just prison; it’s about competition. It’s about the cutthroat, Darwinian, dog-eat-dog aspects of existence, about Capitalism, about the forces that insist upon making room for these baser instincts in our societies even when the positive aspects of civilization should have allowed us to move beyond our most desperate selves. “If they’re content that you / have yet to be eaten,” she ends “Fitness Test,” “that you have, / in fact, been eating others all along, / then they’ll use someone like you. / They’ll call you in. Then call the dogs.” Spousal abuse, harsh parental disciplinarity, disregard for the lives of animals, the recklessness of scientific experimentation — all manifestations of the powerful exploiting the vulnerable are brought to bear on the myriad ways in which we look through the window at somebody being killed, and feel relief.

Nevison marshals and transforms all the tools available as a poet for the complexities of this project. Enjambment turns “God’s hand” into “God’s hand / grenade,” and “In the beginning there was a whole” into “a whole / lot of nothing.” The push and pull of free verse versus the ghost of accentual meter mire us in the sprung rhythm of “The bars lash light across his body,” and enact the repetitive nature of manual labor in “and so you do the work you know you must.” The calming cadence of “I walk and pace to soothe her down to sleep” is jarringly echoed in “a dog can shake / its prey to snap its neck.” In “American Icon,” “Barrel,” and “Chamber,” one of the fundamental building blocks of poetry, metaphor, becomes the site of continuous deferral, critically counterbalancing the intersectional work of the collection to make sure we remember that there’s nothing like prison but prison. Nothing being a word that can render the subject either irrelevant or singular. She ends “American Icon” thus: “Like nothing a child / couldn’t name. Hasn’t seen. / Like nothing, like a game.” The next poem, “Barrel,” starts, “As in what a child crouches behind / when he plays a game.” “Chamber,” which I better print in full, is the best representation of the collection’s fierce interconnectivity; the way that it lights up so many of the things I’ve tried to say in this review is my best attempt at replicating the new reading experience that is Lethal Theater:

As in music, as in a division of the heart.

As in a grave, or a small room, or a house

for a doll or a bullet. As in the body is material

and a bullet shapes it. As in the long hall that stretches

between two people. As in singing, what shapes

the music as it comes barreling down.

Joe Sacksteder is the Director of Creative Writing at Interlochen Center for the Arts and is the author of the story collection Make/Shift (Sarabande Books) and the novel Driftless Quintet (Schaffner Press). Recent publications include Salt Hill, Ninth Letter, Denver Quarterly, and Bateau.

This post may contain affiliate links.