[Influx Press; 2019]

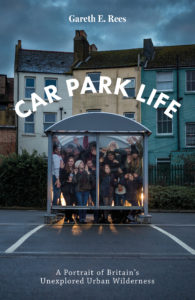

The minute I see the cover of Gareth E. Rees’s Car Park Life, Blur’s “Parklife” starts playing in my head, and the 90s come hurtling into my consciousness. The song is only the third on the google search — but that’s where I’m headed. There it is. Parklife. 1996. The war between Oasis and Blur. I read the wikipage. The origins of the title of the song is a terrible let down, for it seems to have been conceived not in the Estuary that lead singer Damon Albarn’s accent suggests, but bang in the middle of W2, Hyde Park. Having done my bit of online psychogeography, I settle down to read the book, but the rhythm doesn’t seem to match the Blur melody that is now in my head. Rees’s book and Albarn’s lyrics are not from the same hymn sheet. Hope you don’t mind the extended metaphor, because this is what you’ll get from Rees in spades.

When so much energy, air time, and publisher’s agendas are given to the psychogeography of green pastures, it is natural that the literary entrepreneur will look elsewhere. Even Rory Stewart, who’s spent the latter half of his political career fighting for broadband in rural spaces has now gone in reverse. Campaigning to be the mayor of London, he is posting pictures of random car parky spaces in London, and advocating for re-greening these spaces with the hashtag #whynotrees. There are hints in Rees as well, that the car park tarmac is disintegrating, wanting to become wilderness again, which then will be patronized by environmentalists and rewilders, and soon you won’t be able to practice on your gear changes and leave skid marks on the benighted asphalt as a sign of your vehicular prowess.

Rees’s opening gambit is an epiphany he has in a supermarket car park that makes him wonder about the importance of these spaces in contemporary British life. By page four he is asking “Are they simply slabs of tarmac or are they something more? Do they have the potential to contribute something of worth to society?” The answer to these questions is that car parks are the only remaining heterotopia in England in both the urban and the suburban landscape, in a world where every inch is allocated to some purpose. This is where you walk, this is where you play, this is where you park.

One of the problems with Rees’s wonderings/wanderings is that he starts off assuming that he is the first to have found car parks emblematic of 21st century human endeavour. “This challenges an assumed truth” he says, assuming much about the reader “that car parks are non-places without geography, nature, social history or cultural nuance.” When he realizes that he is treading on already well-trodden ground he retracts “When I am told about the existence of [the book] Parking Mad, I feel like Captain Scott when he first saw the Norwegian flag of Amundsen” and as I am about to break into a half smile for the hyperbole, he hammers it home with “Beaten to it” and you realize that the ride is going to be long, with a lot of exposition, not unlike that Small Britain sketch where the tour bus guide says ‘If you look to your left, you’ll see . . . Spain.”

To give some rhythm to the book, I imagine Rees as a radio DJ interspersing his playlist with anecdotes, and the narrative starts to find its pace. I make allowances for the way he just can’t let go of a metaphor, and the way he explains his references a bit too thoroughly. The car being his protagonist, he talks about gas stations and explores our “toxic relationship with the automobile.” “On the site of the Victorian church, they built a petrol station” he says at one point, and just as I am about to enjoy this image he adds “in the service of our oil gods,” killing any subtlety and literary joy I may get out of his figurative language.

Exhausted with Rees driving the same point home over and over again, our imagination is helped by very evocative black and white photographs at the start of each chapter, detail shots from various car parks the author may or may not have visited. These provide the mood music to his at times entertaining ruminations. One of the most dramatic is a photo of “The Ancestor” showing the upper part of a giant statue in Solstice Park in Salisbury, raising his arms to the heavens, initiating us to a solemn appreciation of the “park space.” There is more than “social history” in the car parks, and their most famous historical inhabitant, Richard III, makes an appearance in chapter four. Rees has warned us from the beginning that he will milk every sign and symbol to infuse the car park with meaning. With Richard III this is easy because it appears that the monarch’s bones were found under a faded letter R. “Matthew Morris who found the skeleton admitted that the R was ‘a bit weird’ while the lead archaeologist, Richard Buckley, said the coincidence was spooky. I’m not sure that it was coincidence but an example of urban geomancy” says Rees, and then spends the rest of the book hoping he will come across such signs through which he can divine the state of the nation, but they are too far and few in between.

When nothing comes, Rees reverts to stories from newspapers and courts about the car park being a “nowhere,” where the laws of the road or the neighborhood do not seem to apply. And this is where the book, I believe, is at its best. “[F]orty-seven-year-old named Tracey Ann Hernandez goes for drinks in Llanelli to celebrate her house purchase. Hours later in the Asda car park, three sheets to the wind, merrily performing doughnuts in her Fiat, smoke billowing. She later tells the court that she lives a sober life and rarely goes out.” We understand it was a blip. “This was a blip” says Rees, in case we hadn’t got the point. As we are about to start to sympathize with Tracey, Rees describes the incident once again as a “moment of madness” and then describes it some more.

Things turn darker in other anecdotes. Telling us a story about manslaughter resulting from a park space row, this time Rees knows to let the incident speak for itself, without the usual embellishments: “Holmes, a cancer survivor, whose wife possesses a blue disabled badge takes offence and approaches Watt to remonstrate. In the ensuing fracas, Watts punches Holmes in the face twice. He topples to the ground, cracking his skull. Holmes later dies. Sentencing him to manslaughter, the judge tells Watts that his actions are ‘akin to road rage’” It is interesting to see that the corollary to what a “crime of passion” might be in Mediterranean countries, is parking space delinquency in the UK.

Rees seems much more at home and interested in engaging with stories of car parks than with car parks themselves and is sometimes too familiar with the reader in explaining the pain and effort that went into the writing of his book. It is, one could well argue, a method that men of letters have been employing for centuries. “When you start to write about the connections between people and landscape, the synchronicities keep coming. One story begets another story begets another story. Once that wheel gets rolling, it cannot be stopped,” nor can Rees, once he gets hold of an image or a turn of phrase.

Having shared the mechanics of his creative process several times over, only at the end of chapter four does he decide to share with the reader his methodology, his manifesto, as he puts it, of going about his doomsday book of car parks. You can guess that the items on the manifesto don’t signify much either — “No brutalist porn. No interviews” — as he goes about breaking them, and telling the reader that he is breaking them, in case you hadn’t noticed or did not care. Oh yeah, and then the fifth item “Only five points in a manifesto. I can’t think of any more rules, but five seems like a good number,” ever confident that we are in this writing business together and are happy to pat him on the back for him to go on.

After a while though, Rees manages to garner some sympathy for the citizens of the car park space: the dodgy dealers, joy riders, people battling for a parking space so they can get to bargain sales. The account of people claiming public space, although these car parks may be far from the standard health and safety regulations, starts to sound heroic in a country where most land is owned by the landed gentry and public spaces and buildings are continuously being marked for “development.” There is a very good account of getting lost in one of those shopping strips or complexes, which I believe in America are called promenades, and it has all the elements of folk horror that befits 21st century Britain.

With the advent of online shopping, Rees suggests soon enough supermarkets will be history — and this tally doesn’t even take recurring epidemics into account. “We circle the perimeter hedge towards Pizza Hut lined with rat traps, streamers of toilet roll dangling from the foliage,” Rees says as he describes one of his earlier forays into supermarket car parks. And this image of humans having enough food so feral animals can live on it (have you seen the footage of the gang war between monkeys over a bit of food because there are no tourists to feed them in Thailand?) and cavalier behaviour concerning toilet paper have already become part of social history. It is just as well, then, that Rees has recorded this transitional period of Car Park Life of the early 21st century, for the social historians to come in late 21st century.

Nagihan Haliloğlu is a lecturer and reviewer who lives in Istanbul, where she teaches graduate courses on literature and writes reviews for the Turkish monthly magazine Lacivert. She also occasionally contributes English pieces to Daily Sabah.

This post may contain affiliate links.