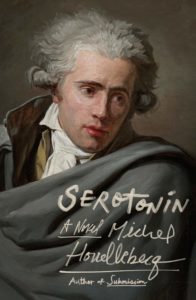

[FSG; 2019]

Tr. from the French by Shaun Whiteside

“By in large it was Monsanto or famine,” explains narrator and agriculture expert Florent-Claude Labrouste with the glib Manicheanism typical of a Houellebecq novel. There is, of course, little room for nuance, or even difference of opinion in the face of a claim like: “without GMOs we wouldn’t be able to feed a constantly growing human population.” Progress is coercive. It offers a way forward and what else are you going to do, be ignorant? Atavism is bad for the developing world. Even when its harms are internalized, opting out of dubious or banal elements of modernity remains inadvisably reckless, as Florent perceives seconds after turning off a popular talk show: “I now had a sense that I was missing something of the reality of the world, that I was withdrawing from history, and that the thing I was missing was probably essential.” Monsanto or famine; TV or oblivion.

Houellebecq sees this as something of a problem. Not just for Florent, his latest toxic, isolated, white, heterosexual, civil servant narrator-protagonist, but for all of “us” in “The West.”

If Hamlet was “unpregnant of [his] cause,” then every Houellebecq character has had a miscarriage. His defeated characters still have plenty of money and material comfort, like France itself, but they have no beliefs, no energy, and ultimately, no reason to continue living, like that debauched and exhausted continent Europe. The plot, like the money, does not matter because there can be no forward action where there is no love, no oceanic feeling, only individual rights, bureaucracies, and progress, things Houellebecq sees as ushers of mass-suicide. Houellebecq has been hailed as politically prescient, but Florent makes it clear that politics separate from these tectonic cultural forces are, at best, an afterthought: “I seem to remember that Emmanuel Macron was President of the Republic.”

Serotonin is Houellebecq’s most direct book, which is perhaps another way of saying it is his least artistic, dragging at times not because it is cynical (though it surely is) but because it is reductive (Eros and Thanatos) and pedantic. “At this stage it might be necessary to provide some clarification about love, intended more for women as women have difficulty understanding what love is for men,” announces Florent, kicking off two pages of admirably undisguised didacticism, in which he channels (and/or namedrops) Schopenhauer, Kant, and Heidegger to sum up the gender dichotomies of love. Yet, when Houellebecq deigns to tell a story with like, you know, characters (not just the archetypal “men” and “women” of his disquisitions), his sensitivity to the tenderness and confusion in something as simple as a glance resonates, “She gave me a weird look, difficult to interpret, a mixture of incomprehension and compassion.”

Florent is a serotonin-taking, and consequentially impotent, middle-aged Frenchman who quits his job and separates from his sex-object girlfriend. Things are vapid and bleak, if not macabre, everywhere Florent goes and for everyone he encounters. At best, some people have prospects that are merely precarious, not yet shattered. The only thing more morbid than the absence of love is the memory of having it, “ . . . I remember her firm little breasts in the morning light — every time I think about it, I have a very powerful desire to die, but let’s move on.” Florent manages only to move on from visions of the petite-breasted Kate to the memory of other, greater former loves, most particularly Celine. Celine is the focus of the book’s strongest sections, in which the existential edge remains but is scrutinized in light of the unreasonable power of their love, creating stylistic, narrative, and philosophical tension. The flashes of lost hope accentuate the present darkness, where pressing ahead seems equal parts pointless and unlikely.

And yet the theme of Serotonin is progress. The narrator, with his keen understanding of commodity markets, is able to show the reader what globalism and GMOs have done to French farmers, or more exactly, what these tools of innovation and expansion have logically and bloodlessly forced the French government to do to a subset of its own people: annihilate them with the most merciless weapon of all, Free Trade. The Gilets jaunes movement lends the agricultural sections of the book topicality, but more interesting is Houellebecq’s examination of the ontology of progress. There is the occasional challenge to modernity on its own terms, such as the assertion that speed limits actually make driving more dangerous, that banning the primal need for speed unavoidably destroys the equally primal survival instincts that undergird basic alertness, “only the discharge of adrenalin induced by speed would have helped to preserve your vigilance.” Cheeky, and such arguments are sometimes legitimate, but they are questions for policymakers — and driving is (by far) the safest it has ever been.

What Houellebecq really cares about, and what he succeeds in making the reader care about, is the state of human relationships in the age of the rational, in which efficiencyis a talisman no one leaves at the office and, as he bitterly satirizes, for a heterosexual man to even consider an arrangement that might strengthen a relationship but damage a girlfriend’s career is a full-fledged betrayal of the Enlightenment. It is axiomatic for the Houellebecqian man that love and reason cannot coexist. A girlfriend’s “realism was therefore an absence of love.” And language itself is an attack on affection, “while a formless, semi-linguistic babble — talking to your lover as you might talk to your dog — creates the basis for unconditional and enduring love.” There are gender implications, certainly, in his call to surrender and enslave yourself to love when for most of history women, and women alone, were forced to do just that. Myriad issues of that nature hover in the background of all attempts to halt or reverse cultural liberality.

Houellebecq may have, ironically, been ahead of his time, though now advocates of social revanchism are increasingly common, in literature and beyond (Patrick Deneen’s non-fiction, Obama-recommended Why Liberalism Failed is a notable example). But convergence with the intellectual mainstream, and his own self-imitating tendencies, have not crowded out what makes Houellebecq unique. His aloof intensity remains paradoxical, provocative, and singular, the atrophy-inducing alienation of someone who has intellectually absconded from everything human while somehow remaining attuned to the redemptive nature of something he believes can no longer exist: an interpersonal relationship uncorrupted by a culture fundamentally hostile to insular and individualized intimacy. Yet, as can happen with a great writer, Houellebecq’s art overrides his diagnoses. He cannot help it. Listening to the story of an amorously thwarted friend, Florent muses that “not only do people torture one another, they torture one another with a complete absence of originality.” But his portraits, always drawn by reminiscing narrators, of transcendent love affairs, are too evocative, too sincere, too direct, too natural, too simple, too privately variegated, and too resilient to exist inside a society he calls uniformly inert.

In politics, the notion of past national greatness has tremendous power; in the personal sphere, conceptions of past love are similarly potent. Houellebecq underestimates the propulsive nature of the latter phenomenon.

His vision of a doomed civilization where monolithic, heartless progress has made it impossible for anyone to maintain their convictions and energy is undermined by Florent’s enduringly salient memories of Celine, which like France’s nostalgia for Les Trente Glorieuses, is an animating force for odd, painful, determined, honorable, delirious, hateful, counter-productive, and even backwards motion (which is still motion) that all remain distinct from laying down to be enveloped by Monsanto, Reality TV, or a “competing” ethos like Islam (which, in Submission, Houellebecq suggests could take over Europe simply because it actually believes in itself). Ruined love is a form of love, and all love is original, and thus so is our suffering, despite Houellebecq’s mass, reverse-Tolstoy diagnosis. All of our torture is unique, which means, for once, we get to be the experts, and it is benevolently heavy-handed scientists and spreadsheets who must defer. That is reason enough for people to keep pushing their rough rocks, custom-jagged, up, down, or around hills, depending on the season.

If you are not so sure, Serotonin is an engaging stress-test.

Erin Bloom is a writer living in Providence, Rhode Island.

This post may contain affiliate links.