This piece was made possible by the Full Stop Fellows Program. Help support innovative, long-term projects on contemporary literary culture like this by becoming a Patreon subscriber.

I might begin: Around fifteen years ago I was waiting for a bus. This was in Tijuana, Central de Autobuses, and I had time to kill. Squeak squeak went my trail runners, fresh from the internet, delivered recently and expressly for this purpose, which was adventure or self-discovery or extravagant mobility. Why does anyone go anywhere? I had a strappy backpack the size of my torso. The kind of open-ended trip on which someone like me packs a tent but also dress clothes. Stuffs in a small library. Adds a snorkel just in case and fins. I had three, maybe four months to kill, and this was day one. Squeak. With some fanfare I had boarded a Greyhound from Union Station in LA that morning, purposeful and adventuresome and twenty four years old. A couple hours later I was in Tijuana, stuck until my next leg, which would not leave until much later in the day, well into the night in fact. Far as I could tell, the neighborhood consisted solely of corrugated sheet metal accordioning into formal and informal auto repair. Inside, the light was undramatic. There was only one other person on the row of very orange molded plastic seating. Outside, lowering sun played off wavy siding and sparks sparked everywhere repair was happening. I was sitting. I was traveling.

*

Or I might begin: How do we write travel now? Should we?

*

I have been obsessing over travel and its writing for ten years now and I am not done. The questions keep swelling, swallowing more terrain. Any answers lie elsewhere. Not in travel literature if by travel lit we mean a chain bookstore’s shelf of post-war British apologists. Not in the refulgent post-colonial fervor of the last two decades wherein academia began (again) apprehending the site of self and other through travel accounts, European and otherwise. Not the seven titles that include the phrase “travel writing” put out by major academic presses in the month of January alone. Not in an online bloom of pro- and paraprofessionals desperate to keep up with a wildfire, all-consuming travel industry. Baedeker turned Lonely Planet turned Tripadvisor turned expat Instagram, replete with influencer gatherings and TravelCons (tagline: “actionable content from experts in and out of the industry”). These sites but also in excess of them. Like little licks at the salt lick of everyplace we can never know, markers and icons of empire, hashtag toponyms cast a net of thin connection and deep alienation, thick connection and thin alienation, of humans and places in exchange, producing and reproducing, wheeling around, like a Julie Mehretu canvas, like whirlpool capitalism, like a shaggy, world-weary heart. In which case, what can new travel writing even mean? If such writing needs a traveler and a traveled-to, how could we hope to scrape subjects off of predicates? Would we want to?

*

“Travel: a range of practices for situating the self in a space or spaces grown too large, a form both of exploration and discipline.” (James Clifford)

*

What if travel were not an exceptional space or extensional practice? James Clifford makes an anthropologist’s case for travel not as sideshow but as constitutive of culture and meaning-making. There are related, less cumbering alternatives. We could say mobility or motility or displacement or diaspora, words with less or different baggage. But these will not suffice. Travel, he writes, “precisely because of its historical taintedness, its associations with gendered, racial bodies, class privilege, specific means of conveyance, beaten paths, agents, frontiers, documents, and the like.” A conglomerate society glued from centers and peripheries and travels and travelers. How in the orbit of global capital, this is every traveler’s power and every traveler’s lament: Even if we go nowhere, even if we staycate, our escape is always into rather than out from under the imperial gaze.

If so, travel’s writing is a problem. It plows past travel’s otherwise policed genres, which are fronts anyway for a bourgeois battle between travel and tourism, a battle whose only loyalists are a line of white men from Paul Fussell to Anthony Bourdain plus, weirdly, outlier immigrants like my father. It leaves smithereens of what we thought were uncomplicated conventions of the form. Whereas a little closer up, everything is suspect. The fiction of a stable subject who maintains uncontested citizenship and unwavering sense of home, one who writes diligently out of a coherent, national experience. The fiction of a stable, sovereign place and time from where such writing is supposed to proceed. Provenance is severed in service of something else. What reader can keep straight what comes from funded fieldwork or from military upheaval, from economic migration or from juicy foreign realia Googled off the couch? A writing from this sense of travel is already broken and dispersed everywhere, consists of dispatches that convey both less than or more than you could possibly see, postmarked out of convenience from the wrong place and the wrong time.

*

Taller, that is what the signs said outside the bus station. The repair shops were talleres. The yolky doble l trickles down the throat. Or maybe, unfamiliar with the pronunciation (more tall?), like a liberal cosmopolitan shibboleth, you feel caught out, annoyed. Maybe you have scrolled back to the author’s last name, trying to divine by what right, via whose politics, he invokes a border city at all. But also talleres, workshops, they are everywhere. Maybe this is what feels familiar. You were not in Tijuana in the early aughts, but where you live or someplace you have seen, a world (the world) operates by virtue of networks of informal repair bounded by sheet metal. You have never been to Tijuana, and here is occasion to feel a little closer. How lovely the Mexican people against all odds (what odds exactly?) maintain a thriving folk practice of repair and creative maintenance. In fact, what if in your institution, that innovative open-plan space aspirationally branded lab or workshop or atelier, what if instead: Taller. An interior tastefully accented by corrugated sheet suggests instability, disruption. Suggests precarity. This is how you make use of everyplace you have been.

*

“Let us not seek to solidify, to turn the otherness of the foreigner into a thing. Let us merely touch it, brush by it, without giving it a permanent structure.” (Julia Kristeva)

*

Italics politics. When I was in grad school for poetry I became weirdly self-conscious about food. I think about mangoes a lot, but I could never include one in a poem, too Asian American Lit or too something. Forget other nouns from my mother’s kitchen, how could I bear the italics? Laden as they are with ethnographic wistfulness and self-othering and uneasy claims on difference, what would a command of italics look like? Whose command would it be? Before grad school my mother visited me in Portland once, I remember us in a natural food store among the bulk spices. Shoppers could smell the italics. She was soon surrounded, peppered with questions about cooking Indian. This was pre-Google, and our white well-wishers needed to know about star anise and black cardamom and taring for ethnicity. I remember feeling the thrill of burnished indignation. Also the thrill of special attention, of basking in my mother’s difference.

Language tracks the vagaries of colonialism, is itself an activity of state sponsored tourism. Vernacular comes to us not from any language of the people but from vernae, “home-born slaves.” Second generation enslaved people born in their master’s house were fluent not only in Latin but also presumably familiar with a mother tongue, literally what their mother spoke, stolen as she was from somewhere else. In Rome, sticking to the official tongue was boring. A skilled orator might be praised for spicing rhetoric with, as Cicero once wrote, “indescribable vernacular flavor.” What a terrible doubling. In mastery, the colonizer holding the tongue of the colonized finds himself imprinted. What would repair look like?

*

Miryam Guba notes of American Dirt, “italicized Spanish words … litter the prose, yielding the same effect as store-bought taco seasoning.”

*

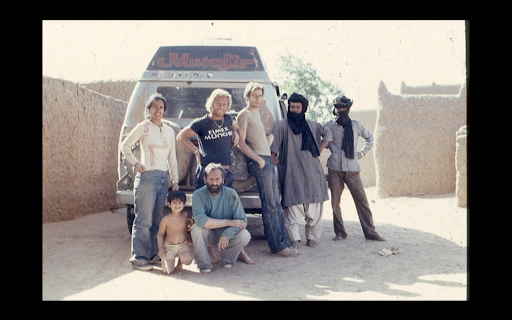

The stakes are personal. Travel is a family compulsion. In the months before I was born my parents and four-year-old brother drove a custom Dodge van from Rotterdam to Capetown. By the time I was 18, I had visited seven continents, which is in every way unconscionable, which in turn led to stints in dozens of countries and states, touring or whiling or, for a few summers at least, leading tours myself. My father refers to himself as musafir, Urdu for traveler. He told me last year, at 72, on the trail or the road, that is how he wants to die. One part romantic attachment to freedom of movement, one part restlessness, one part brittle notions of authenticity and other, my father is a real Oriental orientalist. As I came to see later, he was also, if less obviously, compelled by the gravity of citizenship and class, under the force of which he worked to remake himself after emigrating. A kind of social capital in proving this was not merely what Europeans did. It was not the kind of mastery Indians were expected to command, to wax nostalgic as my father did, embarrassingly and often, about losing oneself in the countryside of country X and finding oneself in a bistro or pub or roadside stall where the regional dish Y happened to be excellent, the best in fact. Formulas that go a long way among Asians and South Asians performing new wealth in suburban Los Angeles.

*

“At the same time travel is not just a matter of going anywhere. People need to travel. They have to go somewhere at all seasons. They have to travel on business, to attend conferences and to reach sporting events or cultural performances. They also travel for family reasons.” (A History of Travel)

*

A passage from Nabokov’s Glory, written in 1932 though not translated until 1971:

“Travel,” said Martin softly, and he repeated this word for a long time, until he had squeezed all meaning out of it, upon which he set aside the long, silky skin it had shed–and next moment the word had returned to life. “Star. Mist. Velvet. Travelvet,” he would articulate carefully and marvel every time how tenuously the sense endures in the sound. In what a remote spot this young man had arrived, what far lands he had already seen, and what was he doing here, at night, in the mountains, and why was everything in the world so strange, so thrillful? “Thrillful,” Martin repeated aloud, and liked the word. Another star went tumbling.

*

In Glory, the extreme privilege of Martin, our young emigre protagonist drunk with mobility, whose physical dislocations and will to disappear culminate not up a muddy river into a heart of darkness or cartoon shipwreck island, spread of sand interrupted by a single palm. Instead he is at a border. Though his grandfather was Swiss, he is trying to smuggle himself back into Russia where he was born, now the Soviet Union, a place that was anyways never his. As the novel progresses, we only learn of Martin’s whereabouts via increasingly infrequent, misdirected postcards home. That is, until he finds a willing smuggler, at which point he attenuates then disappears into the wilderness past Riga, down a path suspiciously like the one in a watercolor that has haunted him since childhood. Martin’s epic is a quest for a site to situate himself, journeying after a place both home-like and foreign–originary, authentic–a place he can finally pour himself into. Instead of which, he can escape only into the stylized pastoral, to the picturesque. The eros of specificity co-opted by its irresistible replica, its postcard.

*

Whatever he was, I knew he was a fellow traveler, the strange American specimen next to me, the only other person waiting in the little waiting area designated for buses like mine. Sun-ravaged, white hair to his shoulders, his nose was distinctly bulbed and pocked. All stick and knob, here was a body ill-suited to manufactured clothing let alone manufactured environments. He clutched a deflated book bag looking everywhere but at me.

I was brown and young. He was white (red, really) and old. Yet, I knew he was American whatever that might mean, which evoked a complicated mix of outward trust and veiled hostility. His appearance, his ratty expression, nothing he gave off would invite anyone nearer. But he had clearly had an adventure of some kind, and maybe I was a little envious. First day of my trip and the first occurrence of the two animating questions of the traveler: Where was he from? Where was he going? In my everyday, I take people as wholly formed entities deliberately emplaced. But when I am traveling, I am a mark along a trajectory as is anyone else I encounter, every body, a body in motion. Here I was astonishingly still, having waited hours, with so many more hours to wait. In this station. At the intersection in the desert I would be left at several hours later. At the ferry terminal after that. For the next ship or pickup truck or cooperative minibus, for the rest of this particular journey I would always be waiting. So much fucking waiting. In recounting the trip it will sound like magic as I skip from vignette to vignette, and it is magic the way I manage to blank out what volume of my life I have hemorrhaged into provisional spaces neither here nor there.

*

“[A] form both of exploration and discipline,” writes Clifford. Travel as a form of disciplined immobility as in stay seated while the cabin is in motion. I think of the backdrops hand-painted by inmates in visiting rooms across the American penal system like those collected by artist Alyse Emdur in the photography project Prison Landscapes. Loving imaginaries of forest waterfalls or Mediterranean villas or sunset beaches or urban skylines, a visual language with which to exert a tiny flick of control over self-representation. If one is to be depleted of mobility, rendered incorporeal, unembodied, why not let your loved ones imagine you triumphant over a painted bass pulled from an overstocked acrylic creek or contemplative before scattered clouds lit by a setting equatorial sun? Each mural in each visiting room is a text on travel to which we ought to be paying rapt attention, attesting to the state’s chokehold on discourse but also to the borders which agency finds itself tiptoeing across.

I read about a practice in China that translates as “to be touristed,” by which some veteran dissidents avoid further detention during sensitive periods–a state visit, an international sporting event. Instead, their secret police minders, the same officers parked conspicuously in front of their homes, might whisk them off to prominent domestic tourist sites. In lieu of disappearance, detainment, and torture, you might take in a lakeside resort or view a terracotta warrior or otherwise celebrate Han splendor. Your secret police might take a picture with all of you in it, a body of water in the background and sky in the water. Strange incentives. Such tourism is available only to dissidents irksome and visible enough and to police who have through appalling, unending drudgery earned a little perk.

Travel is compulsory. We must always think of and be thought of as elsewhere. Perfect confusion of carrot and stick, the state bleeds into internalized technologies of discipline while against and with these technologies, a tenderness shows. In the visiting room, the lavish, immoderate attention paid to painting the motion of the water or the sunlight reflecting up under the branches of a woodland scene. Or on tour with one’s prisoner, the surprise deference a low ranking officer pays the older dissident, who is in this strange constellation his boss, his supervisor, his tour guide. There is a care here, fugitive, excessive, the text of which is both coerced and exceeds enclosure.

*

“[I]t is no longer from the practice of community but from being a wanderer that the instinct of fellow feeling is derived.” (Raymond Williams)

*

We began to talk, this American and me. We were on opposite ends of our journeys and maybe he saw something of himself in me. His voice sounded like he did not use it much. What was that accent? Maybe Southern or New England or English or Australian, but it was none of these. It was like sand. He began recounting a life stitched together by sailboats. As he warmed to his own story, there were many details but the arc I had to trace for myself. People sometimes need help captaining or crewing their boats if the length of the intended voyage is long or the route unfamiliar. People need their boats sailed on their behalf to or from a marina if that marina is not where they happen to be. People in marinas need help cleaning and maintaining boats, they need help buying or selling boats. If you are at it long enough, likelihood is you will obtain a boat of your own every once in awhile to spruce up, to live on, and to sell later. If it does not much matter at which marina you find yourself, as it did not to this American, you can string together many marinas this way.

The American was not charismatic, spoke with an awkward intensity. He began around my age at the time, and through these sailorly activities, strung together broad swaths of the South Pacific, colonies and former colonies, fishing villages and mooring for super yachts, gigs stewarding the ultrawealthy and stints sheltering under dropped palm fronds. He described mapped and unmapped islands and untaxable income. He described months alone or with a woman on unnamed atolls fueled only by coconuts, colorful fish, and desalinated water. This is how he had strung together a good portion of his life, hardly documented, without a state to speak of.

*

The project of travel writing is to make more of itself, creating and disseminating transparent eyeballs to roll all over looking – autonomous subjects, colonial surveillance, unanchored Anglo-Americans, chapped and aging, trapped in bus stations across Mexico – looking everywhere but back at their own dominion. The project of travel writing is to tactically fail at this. Travel writing instead reports on and reports from shifty, situated spaces rife with historical bodies. I hear the ghost of other reports, as in explosion, gunfire, of violent displacement. The air suddenly replaced with new air. Travel writing is always opening out onto what is specifically and manifestly possible: The world.

The story now, not unlike the old story, is of loss, a foreclosure on homes and senses of home. Whichever tide, you can hear it rising. Whatever the tenor, intentionally or not, travel writing trawls the wreckage that preceded the recent boom, unfurling no less than the world-building, self-generating activity of language, no less than the world-destroying, self-abnegating activity of language itself. How desperately useful are these dispatches from elsewhere when a world starts narrowing in around us. Kristeva: “Henceforth, we know that we are foreigners to ourselves, and it is with the help of that sole support that we can attempt to live with others.”

*

I was devouring all of it. Despite whiffs of prolonged, corroding loneliness, as he talked, ways of inhabiting a life I had not known possible bowlined into existence. My first day on an indeterminate journey and here my first Encounter was with this wiry, shipwreck of a human, who after at least eleven years at sea interspersed with years along other detours, at 73, was finally looking towards a suitable end to his story, which he believed was in Costa Rica. By now I had gravitated beside him, smitten.

In time there were growing lapses of silence. We had both met or exceeded our daily allotment of sociality. Then he got close, gripped my arm suddenly. “Don’t,” he said hoarsely. There was desperation. “Settle down. Find a wife.” This was a surprise turn. I did not want to be this man but neither did I not want it. I wanted above all for him to believe in the exception and wonder of his life choices even if I could not fully. Instead his narrative was undoing itself and it was heartbreaking. To what should I be wed?

*

Travelvet: A busted, colonial genre harboring tender acts of repair, indicting us, placing us in relation to one another, opening real and imagined space, untied from its mooring. Let me tell you what the place was like, the people.

Nabil Kashyap is one of our inaugural Full Stop fellows. Nabil is the author of The Obvious Earth, a collection of experimental essays on travel. His poetry, essays, and reviews have appeared in Actually People, Colorado Review, DIAGRAM, Full Stop, Seneca Review, Versal, and elsewhere. He was awarded fellowships by the Vermont Studio Center and Headlands Center for the Arts. He is a librarian at Swarthmore College and lives in Philadelphia.

Nabil’s fellowship project will continue to explore what travel and its writing might look like now through a series of dispatches from his encounters with writers, artists, and texts.

This post may contain affiliate links.