[BOA Editions; 2019]

[BOA Editions; 2019]

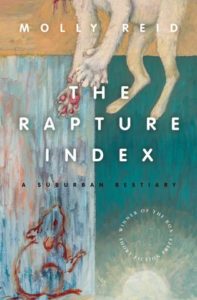

The cover of Molly Reid’s award-winning debut collection of stories, The Rapture Index: A Suburban Bestiary, features a painting titled “Claws” by artist Elizabeth Albert. Pictured are one and a half animals. A sketched mouse, crouched at the bottom corner, looks up at the clawed paws and lower body of a creature whose torso and head exceed the top frame of the book. The truncated creature suspended above the mouse appears to be a white house cat, although the rear legs also suggest a rabbit – perhaps a chimera. Set against bold brushstrokes that evoke movement, these critters are enchanting and mysterious, fitting for the stories contained within. The mystery of the image inheres in whether the upper animal is falling or rising – whether the claws are barreling down from on high to eviscerate the mouse or rocketing upwards and away. Are we witnessing gravity in the service of nature red in tooth and titular claw, or are we glimpsing an unnatural – supernatural – intervention? Is is it the predator or the prey about to be taken?

Another way of putting this question: which animal is on the brink of rapture? As Reid explains in a recent interview with Kenyon Review, “rapture” is for her an interesting term for its religious as well as its corporeal connotations. In the religious sense, rapture refers to the Christian idea that “good people [will] one day simply disappear, sucked away into everlasting pleasure, leaving the rest of us to suffer in agony.” It is this sense of the term that undergirds the real-life website that inspires Reid’s title. The “Rapture Index” site quantifies and compares various global indicators of the ensuing apocalypse. In its own terms, the project does not predict the rapture so much as it “measure[s] the type of activity that could act as precursor to the rapture.” But more resolutely this-worldly than an end-times barometer is the other meaning of the term “rapture” that engines this story collection – the meaning linked to the body and to what Reid calls the “pursuit of physical rapture.” This latter type of rapture is characterized by joy, ecstasy, bliss, euphoria, etc. Yet there is a totalizing force involved that verges on violence. Christian rapture is being taken from this world to the next; physical rapture suggests its own sort of evacuation – a being taken from oneself by the throes of outward-driving desire. If the upper creature of the cover image is perhaps caught in a spiritual rapture whisking it up from this earthly plane, the mouse may be about to experience the more bodily sense of rapture – ravishment by consuming hunger.

With this indeterminate blend of the religious, the quantifiable, and the carnal evoked by the volume’s title and cover illustration, Reid’s stories go on to explore the myriad valences of rapture as well as the ambiguous space between. Thirteen short stories focus on intimate relationships cast in the shadow of larger forces and events. Framed here and there by anticipations of the Christian rapture, by actual apocalypse, and by more wrenchingly mundane issues of loneliness and loss, the stories thread the tenuous small bonds of lovers, families, friend groups, and even pets. Occasional interventions of the odd and the speculative speckle these compact encounters. But mainly the characters circle in muted domestic dramas, some drifting apart while others are caught – enraptured – in compulsive sexual attractions and superstitious devotion.

Interspersed between these thirteen character-driven stories are eight flash fictions titled as entries in Reid’s “Suburban Bestiary.” A bestiary is an ancient genre that compiles information and illustrations related to beasts, real and imagined. As Reid notes in the interview mentioned above, these projects mixed “natural science, storytelling, and Christian morality” with speculation and interpretation, finding in animal forms provocation for addressing all manner of human concerns. In Reid’s deployment, however, the bestiary also evokes another tradition of ancient storytelling: the Greek chorus. Because if Reid’s more conventional short stories focus on characters in intimate orbit, the bestiary tales channel the collective voice of a larger community. Focalized through the plural perspective of a we and an us that sees and knows capaciously, these entries each take up particular beasts – a flock of birds, an ornery raccoon, a bobcat that resides in the local laundromat. Shifting from one animal interloper in suburbia to another, the tales zoom up and away from character specificity, framing the goings-on from an abstract detachment. The first bestiary, for instance, tells of “the neighbor’s bees,” which have been “reported to swarm the lustful.” Questions of whose neighbor we’re considering and who reported this swarming are of no consequence. Though the narrator speaks from the first-person identity of “I,” the resulting voice sounds diffuse in time and space. Such a floating collectivism endures through later entries and is most striking in the final bestiary, which describes erstwhile pets rising up in violent retribution, as if “to finally enact the nightmare we had initiated.”

But the short stories are not wholly divorced from the bestiary entries. The two modes mingle, for instance, in “Anatomy is Destiny,” a story about couples coupling while hummingbirds buzz around offering enigmatic whispers at the window. Similarly, one especially short bestiary tale blends authoritative ornithology with the simmering private shames of mortality and masturbation. The first story of the collection actually offers the most thorough joining of Reid’s two main narrative modes. “Happy You’re Here” follows two siblings as they say a protracted goodbye to their mother dying in the hospital. Outside the window and down the street from this private mourning, however, the town’s beach is thronged with people eager to ogle a beached whale. Fetid and bloated, the dead whale swells as the onlooking audience grows. The narrator flits between these scenes, the claustrophobic indignities of human frailty set against the open-air spectacle of rotting fish flesh. Here the personal and the animalized plural co-exist, bleeding into one another. While Reid mentions in her interview a number of authors who have inspired her, this volume’s juxtaposition of character focus with animal ambience reminded me most of Lauren Groff’s recent story collection Florida, which shares with Reid a sense of the fraying boundaries between the tame and the wild.

And yet elaborating Reid’s two dominant modes and their mixings does not exhaust this volume. A number of stories actually do something rather different, opting for meta-fictional and experimental form. One short piece about all the ways to fall down – and to feel oneself being caught – is reminiscent of Donald Barthelme’s micro stylings (and was, it turns out, given honorable mention in Gulf Coast’s 2016 Barthelme Prize for Short Fiction). Elsewhere, in “Adventures in Wildlife,” we’re treated to a carnival ride of teenage lust that reads a bit like George Saunders rewriting Ray Bradbury’s “The Veldt.” Another more ambitious approach, “All Men,” might be described as a choose-your-own-feminist-adventure story that prominently features Baba Yaga, the witch of Slavic folklore who lives in a house supported by giant chicken feet. Still another story begins more conventionally only to end in a loop with its beginning, adapting the labors of Scheherazade into the contracted task of a corporate-funded “ghostwriter” drafting his own story.

Given this range of approaches, it is remarkable that Reid’s collection feels cohesive and full. Especially given that nearly all of the stories were published previously, this cohesion is enviable and impressive. Part of the trick lies in Reid’s patience to interlock the stories, dropping stray hints, names, and events that yoke together the stories across the volume. But this enmeshment only matters because the underlying tone and sensibility remain consistent. Whether more straightforward, bestially short, or wryly innovative, each story feels poised in the rapturous instant of the cover image – hovering somewhere between dread and wonder in a world on the edge of ending.

Ben Murphy is a PhD candidate and writer studying American literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His academic research appears in Mississippi Quarterly and Configurations. Other writing—including essays, reviews, and interviews—can be found at The Millions, PopMatters, symploke, boundary2 online, Full Stop, Gulf Coast, and The Carolina Quarterly. He tweets @benjmurph.

This post may contain affiliate links.