[Wave Books; 2019]

[Wave Books; 2019]

Edited by Ben Lerner

I came to Keeping / the window open knowing I would feel a deep kinship with the book. Not because I’m friends with the Waldrops – I’ve never met them – but because of what I want from poetry: not answers, but the space of wonderment, a space that can come from any number of poetic approaches but that’s palpable, pulsing for me in Rosmarie Waldrop’s writing. When I talk to my students in workshop about “your ideal reader,” the example that’s in my mind but I never say out loud is this: me reading anything Rosmarie has written. I don’t fully understand the complexities of, for example, a stanza like this one from her first book, The Aggressive Ways of the Casual Stranger,

Lids still weighted

surface from

deep liquid pleasure

unknown

in the air where I carry my head

approximations

find the mouth

blocked

turn back into desire

to be one with

the murky

a point

within the black

but the complexity of the lines – assembled by seemingly straightforward language – sends me back to the beginning again and again. This is what Emily Dickinson meant when she talked about the top of her head coming off; I feel the embodied sensation of being stunned when I read Rosmarie Waldrop’s poems. And prose. And translations. So look, there’s no way this is going to be an objective review (see exhibit a, exhibit b), and rather than try to give an dispassionate assessment of Rosmarie Waldrop’s and Keith Waldrop’s Keeping / the window open, (it surpassed my expectations, though, if you’d like to know), I’ll resort here to summary and impressions of what the book is doing overall.

This book is a retrospective. It’s a gallery show, a special collections exhibit, an intimate conversation about writing with a couple who’ve spent their lives making and sharing works on paper. If the translator can be invisible when they create a text that meshes somewhat seamlessly with the reader’s cultural and linguistic associations, then an editor can also be invisible when they curate a sampling that captures the complexities and textures of the whole. This is what Ben Lerner has done; he has presented a cropped close-up of the Waldrops’ years of making.

The book offers poems paired with ephemera and archival material, some of it difficult to find or out of print. Keeping / the window open (edited by Ben Lerner) is the second volume in Wave Books’s burgeoning Interview series; Joanne Kyger’s 2017 volume There You Are: Interviews, Journals and Ephemera (edited by Cedar Sigo) was the first. This series reminds me of the CUNY Center for the Humanities’ Lost and Found series because of its archival nature. Keeping / the window open showcases three hundred and seventy-one pages of material, including photographs, poems, collaborative writing, event flyers, dissertation pages, translation notes, essay excerpts, and interviews. Early works date back to the 60s, during the Waldrops’ time in graduate school at the University of Michigan.

Some entries take up only a page or two, while the longest works, like the co-written Ceci n’est pas Keith / Ceci n’est pas Rosmarie and Peter Gizzi’s interview with Keith Waldrop are quite long (roughly forty-five and fifty-five pages, respectively.) The Waldrops ran Burning Deck press from 1962 until 2017 and, in the beginning, used their own letterpress for printing. This is a book about book arts as much as it is a book about poetry. The book has numerous scans, creatively arranged and often accompanied by captions that look like art labels. The design of the book alone makes the material – typewritten pages of Keith’s PhD dissertation on obscenity and aesthetics, for example, or a hand-written, copyedited draft of Keith’s translation of Claude Royet-Journoud’s poem next to the final printed version – feel like a gallery exhibition.

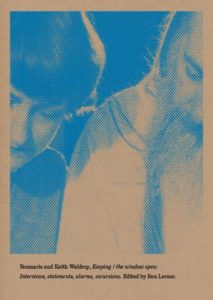

Jeff Clark, who designs all of Wave’s books, visually joined the series through their covers, printed on unbleached card stock and featuring a photograph of the author (or authors, in the case of the Waldrops), in blue. Each cover photo crops and dithers a facial close-up from the photo that appears in full, opposite the title page. Because each volume can only give a small taste of the author’s oeuvre, we end up with glimpses and fragments from decades of work. In this way, the choice of blue and dithering bring to mind Rebecca Solnit’s “The Blue of Distance.” Her essay riffs on the idea that we see blue in water and air because it “disperses among the molecules of air, it scatters in water.” The blue is what remains out there – illuminating the gaps between the sun and the eye. This is a fitting metaphor for an ambitious series.

The stanza above from Rosmarie Waldrop’s first book of poems appears in Keeping the window open, as do Rosmarie’s statements about her first book. In one place she says, “Consciously I was pushing at the boundaries of the sentence. I was interested in having a flow of a quasiunending sentence play against the short lines that determine the rhythm. So on one level, I was simply exacerbating the tension between sentence and line that is there in all verse.” She also says of her early work that she was “pushing metaphor out of the texture into the structure,” a strategy she connects to French writer Claude Royet-Journoud and their similar movements away from image and analogy, toward grammatical play. She explains, “in both our cases, the raw experience of war is no doubt the more crucial ’cause’ of this turn against images, even if we were children, even if it is impossible to pin down precisely.” The accumulation of background information alongside selections of the poems gives the reader a glimpse of art as life, or the conditions that produce a lifetime of art and partnership.

The sprawling, wide-ranging interview between Peter Gizzi and Keith Waldrop toward the end of the book gives a solid history of the wild, serendipitous events leading up to acclaimed composer Robert Ashley’s recording of In Sara Mencken, Christ and Beethoven there were men and women, and it lays bare some of the procedures behind Keith’s writing. After recounting the found poetry techniques he used for writing The Antichrist and Other Foundlings, Keith explains that “members of the Oulipo have disagreed on whether, having arrived at a text from a certain technique (a restraint, they would call it), one should reveal the technique or simply give the resulting text.” Keith’s in the camp of only presenting the work, so a book like Keeping / the window open provides a contextual glimpse. This interview alone is reason enough to get the book; not only for what the conversation reveals about Keith’s work, but for the dance of conversation.

Aaron Kunin explains in the introduction that both Waldrops, “are drawn to collage and translation, kinds of writing where, at the start of the process, some text already exists and the writer’s job is to make a different text out of it.” Given this inclination, the interrelation of materials here mirrors the Waldrops’ process. Everyone will discover something new; this is a book for dedicated Waldrop fans and unacquainted readers alike.

Laura Wetherington‘s first book, A Map Predetermined and Chance (Fence Books), was selected by C.S. Giscombe for the National Poetry Series. She has a chapbook just out from Bateau Press, chosen by Arielle Greenberg for the Keel Hybrid Competition. Laura teaches in Sierra Nevada College’s low-residency MFA program.

This post may contain affiliate links.