© Polly Antonia Barrowman

Amina Cain writes by sight and habitation. Her writing is often mysterious. The author of the short story collections Creature (Dorothy, 2013) and I Go to Some Hollow (Les Figues, 2009, now out of print), her first novel, Indelicacy, is newly released from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Cain has described the novel’s narrator, Vitória, as a flâneuse, wandering absorbed through her city and through her life, as a cleaning woman at the museum through marriage to a wealthy man. Vitória’s narration is quiet, pensive, and engrossing, whether she is describing beloved works of art or her own prejudices. The novel is a beautifully composed and observed work centered on the complexity of inner life as it clashes with the demands made on it from the outside, whether it be friends, family, community, or commerce. After apologizing for the background noises of our respective cats, we talked on the phone about form, space, influence, and the self in her work, as well as our love of small presses and our hatred of Vonnegut’s rules for writing.

Kyle Williams: Your writing is intensely compressed; When I recommend your books I tell people it goes beyond minimalism into a sort of “microminimalism,” if you will. How are you thinking about that compression; do you have a philosophy behind it?

Amina Cain: In a way, but I’ve come to it through the process of writing; I’m not necessarily starting with it. I’ve talked about this before, but I had a realization a few years ago that I’m always trying to empty out space. Not just in writing but in my life, too. The house I share with my husband is extremely minimalist, so much so that a friend once asked, “What are your plans for your living room?” and I said, “We’ve done it. This is it.” I moved to LA partly because of the desert that opens up when you drive out of the city. And of course this has carried over into my writing. In hindsight, I realize that it fits in with my love of imagery. What I mean by that is, if I’m writing a scene and setting it in a room, for instance, I’ll often get focused on just a couple of visual details because I feel that when everything else is cleared away and I’m just looking at those two things, some strong feeling can arise from that.

I tend to write through a kind of seeing. I’m not a visual artist—I can’t draw, I can’t paint—but I think as a fiction writer I often work in similar ways so that I am, with setting, with these details, making compositions.

That draws me to a part of your work I always find really interesting, which is the sentence. I’m always attracted to writers who can make the sentence feel like a new technology, and I get that feeling from your writing often, that you’re finding something new to do with the sentence that goes beyond Vonnegut’s rules of forwarding plot or character.

Terrible.

Terrible. But so when you’re composing a sentence, is it the visual you feel moving you forward?

It’s often a combination of the visual and of narrative voice—how those two things come together as well to create something. Sentences are important to me; they have the potential to be so alive, so activating in their own right, not just at the service of plot. In that way, I feel as close to poets as I do to fiction writers.

Your first two books, Creature and I Go to Some Hollow, are both short story collections published on small presses, Dorothy and Les Figues respectively. Your new book, Indelicacy, is a novel published by a major house, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Does that trajectory feel related to you, from short story to novel, from small press to major house?

I don’t know if people still think in this way, but when I was in graduate school and writing short stories, people would say to me, “Short stories don’t sell, you should write a novel.” I was always like, “Oh well, the short story is my form. I don’t want to write a novel.” But when I was working on Creature something changed. I was starting to move toward more of a singular voice in those stories, and I kept writing about maids and cleaning. It felt like a natural thing to stay in that space for a while. I also wanted to challenge myself as a writer, because a novel was starting to feel like such a daunting thing to me, this space I had nothing to do with.

Did you start writing Indelicacy shortly after finishing Creature?

I did, although I had to do this year of writing that didn’t make it into Indelicacy—a sort of pre-writing phase. It took that whole year before I reached what I think of as the real space of the novel.

And you did stay in that space quite a long time; Creature came out seven years ago now.

I started what is now Indelicacy probably in the Spring of 2014. In terms of the presses—I write such slim (and yes, compressed) books that in the past I never really considered submitting my work to a large publisher, because most of them don’t often publish shorter works. It wasn’t that I thought that since I was writing a novel I should try to publish it with a bigger publisher, more that it seemed to me that that world was becoming more open to different, and stranger, kinds of fiction, partly, I think, due to publishers like Dorothy, who publish outside of those concerns about length and marketability, who are interested in the possibilities of fiction, not in shutting those possibilities down.

I have felt that larger publishers are constantly playing catch-up to the small press world.

I think so. But, having Jeremy Davies as an editor—who is also this great and interesting writer I feel some kinship with, and before being an editor at FSG was at Dalkey Archive—makes for a really nice continuity from working with editors like Danielle Dutton and Marty Riker at Dorothy, who are also phenomenal writers with whom I feel in kinship. In that way, it’s part of the same constellation.

To ask a bit more about Indelicacy: In an interview you did with Renee Gladman for BOMB, which was kind of a while ago now, you talked a lot about slowness. Specifically, you talked about Chantal Akerman, which really opened Indelicacy for me, because it does sort of develop like an Akerman film, in the way the scenes progress being both a challenge to traditional narrative structures but also the logical extreme of realism and verisimilitude. Indelicacy both does and doesn’t play like a traditional novel—there is an element of bildungsroman or even kuntslerroman, but there is also not a strict plot structure. Is slowness a way of getting at the novel’s central narrative structure?

Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman is an extreme example of that slowness. The first time I watched it I was amazed at how slowly it went, how slowly a film could go, how little could happen, how quiet something could be. It was the first moment in which I found myself both bored and exhilarated by something at the same time. It’s something I find in Clarice Lispector’s fiction, moments that are almost excruciatingly boring, and yet it is a desirable boredom. I almost can’t explain it, because normally when I’m bored it means I’ve hit some wall, but this is a boredom in which something opens up. It might also be why I first became drawn to meditation, which can feel excruciating even as it opens something you can only see in that exact experience.

It’s almost a risk to talk about meditation, because I don’t do it as much as I used to, but when I went to a weekend retreat, for instance, I both hated it and it was the only thing I wanted to be doing.

But also, in terms of process, I’m a really slow writer, so much so that it starts to enter into and interact with what I’m writing. Again, though, slowness isn’t something I think about while writing. Similar to the way I might write sentences, there’s no theory behind it, but in hindsight I can see what I’ve done and begin to understand why I’ve done it.

In that way, then, these things emerge from your process, rather than them being the intentional pursuit of your process.

Yes. And I believe very much in absorption. If you read a lot of books, and watch a lot of movies, you’re going to absorb some of what it means for you to read and watch them, and that will be expressed in some way in your own work.

In another interview, also a while back, that you did with Sofia Samatar, you mention you saw writing as an expansive field, and fiction as a place where anything is possible, including other kinds of writing. I thought about this a lot in Indelicacy, when it came to Vitória’s writing throughout the book—these ekphrastic meditations on the art that she’s seen or meditations on certain images. Is that related to this idea of absorption—that maybe this is a kind of writing that fiction makes possible?

I do want fiction to be a space where anything is possible, and I believe that it is. Ekphrasis in Indelicacy comes a lot from a love of imagery, and part of the process of writing the book was about looking. Vitória comes to writing through looking at art. And being a writer who feels hugely inspired by other writers and books, but also by painting, performance, dance, music, etc., I can’t help but engage with those forms—I’m so interested in what they do, and whether or not fiction can be a form for what they do as well. Through writing, I can explore those forms in my own way, stay in them longer than I might be able to otherwise.

Throughout your books you wear your influences on your sleeve. There’s a really wonderful reading list in your acknowledgements pages, if you’re looking for it; you have characters named after Clarice Lispector and Marguerite Duras; there are passages in Indelicacy—though I would not be able to find them—from Lispector, Jean Rhys, Jean Genet, and Octavia Butler. When you’re engaging with those influences, do you see it as a way of inhabiting the spaces that those writers opened up for you?

I do. When I read a book I love, I just find it so pleasurable to be in the space of it. In Indelicacy, the four female characters are named after characters in other books: Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys, The Maids by Jean Genet, Kindred by Octavia Butler, and The Apple in the Dark by Clarice Lispector. It’s not that I felt I was rewriting those characters, but honoring those characters and those writers, paying homage to their influence, being grateful they exist.

And maybe engaging with the lineage?

Definitely.

This might be a question more for me than anyone who would read this interview, but I really want to ask you about Violette Leduc. She’s the epigraph for Creature, and she’s definitely an obsession of mine, I’ve read all of it, and I’m curious what you got out of reading her, if that doesn’t seem like an absurd question.

I’ve only read The Lady and the Little Fox Fur and La Bâtarde, but I feel especially influenced by the former, which is where that epigraph comes from. At the time, in Creature, I was also starting to write stories that dealt with poverty, especially among women, and the main character in The Lady and the Little Fox Fur is a very poor woman, and yet there are descriptions and scenes that read very pleasurably, even mystically. Often with impoverished characters in fiction, you don’t get that.

Like they feel more like representations of characters or political slogans than real people.

Yes, representations of issues, not real people, and not complex experience. And pleasure is something I’ve been interested in—writing about pleasure, writing about different people’s relationships to pleasure. These things have of course carried over into Indelicacy—issues of class, money, and pleasure. There’s a sort of history of women who clean in my family—my grandmother cleaned hotel rooms in Daytona Beach, Florida, for example. I spent a summer on the cleaning crew at Tassajara, a Soto Zen Buddhist monastery in Carmel Valley, California, which opens up its cabins during that season to guests, and people with a lot of money come there then, so I had to work on my own class issues while cleaning up after people I perceived to be rich, and therefore very different from me. So the class issues in Indelicacy, which got started in some of the stories in Creature, and tie into my connection to The Lady and the Little Fox Fur, are something rooted in me that I needed to explore.

There are some really interesting comments on class and politics in Indelicacy. I’m so glad we got to talking about that from Violette Leduc.

It’s interesting, at one point when I was writing Creature someone commented, “You don’t really engage in the political in your writing.” And I remember thinking, yes, in a way that’s true, but also it’s not true, there are different registers of everything, including how we might write about the political. I may not engage with it overtly, but in smaller ways I do.

Not didactically, anyway, which I think is how people are used to novels engaging in politics, these tired sort of “Rich people are bad” economic moralist narrative motions. But to say that your writing is apolitical feels wrong, especially thinking about the ways gender and sexuality is approached in the novel, and in the stories.

I feel like that. As a writer, I’m interested in quieter tones, in subtlety, though I value directness as well. Something that’s become more important to me is the idea of the authentic. I’m still working out what that means, but in Indelicacy I feel that it has political implications. Again, I didn’t start with that as an intention, but it’s interesting to see what starts to emerge when I’m writing. It’s funny, I often talk about writing as something that happens outside myself; I’m hardly ever like, “I set out to do this,” but more, “I watched this happen.” It’s very subconscious, and I enjoy that emergence. I find pleasure in seeing what strains of thought emerge together, to see what they create.

This idea of authenticity is, I think, a good place to ask a last question. I think a lot about the self when reading your work. Your narrators often delineate the self, sometimes even explicitly. Thinking about Indelicacy, especially as a bildungsroman moving Vitória through these spaces the self inhabits—when alone or engaging in community, commerce, family—the political ramifications of the novel come through most when those spaces are in conflict with one another. How do you see the position of the self in contrast to these spaces, especially thinking about Vitória?

I’ve been writing “the self” for a while, and my conception of it now is a lot different than it was when I was writing Creature. As I get older, the self has become more and more mysterious to me. It eludes me more and more, and as time goes on, becomes unstable (like the title of Elisa Gabbert’s wonderful book, The Self Unstable). In the novel, Vitória comments, “What I thought and what I said were two different things,” and that’s something I experience a lot. What the self is in the face of commerce and community has changed, and is continuing to change, in ways that I actually find very difficult and alarming. When I am with people I love and who love me, I can feel something like, “This is my true self,” but in the face of commerce or social media, which are nearly the same thing now, that self gets almost totally obliterated. Not to be dramatic, but it feels fraught. My interest in the authentic may be because I feel I have lost sight of the authentic self, if that’s even something that’s ever existed, or can exist. I don’t think it does, but still I want to get closer to it.

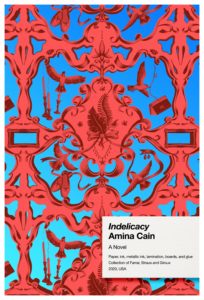

Indelicacy

by Amina Cain

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published February 11, 2020

Kyle Williams is a writer living in Brooklyn. He is an Interviews Editor for Full Stop, Director of Communications for Chicago Review of Books, and A Public Space’s 2019 Emerging Writer Fellow. He is on Twitter @kylecangogh.

This post may contain affiliate links.