[Sixth Finch Press; 2019]

On the opening page of writer, artist, and educator Angela Veronica Wong’s newest chapbook, Animal Suicides, many readers’ eyes will be drawn first to the lines in the top-right corner of the first page, “committing suicide / this way. i am hopeful.” Strange. Unsettling, even. These lines are the final lines of the first “chapter” of the text. To complicate matters further, this first chapter is titled “Chapter 2,” making a reader, even before the actual first line of the collection, doubt the stability and authority of their perspective. Even so, the more official opening sentence of the collection, positioned almost half-way down the left side of this first page, is no less unsettling:

get married so we can

die together you’re a

motivational speaker i

am a therapist.

Who is this speaker? What kind of a world are they speaking from? How can death generate hope? How might death be necessary for hope? How can presence inspire absence, and how can presence even be a form of absence? Wong describes her chapbook as, “an exploration of happy things like animality, humanity, waste and excess, legacies of colonialism, environmental degradation and ecological disaster, travel and nature documentaries, and violence.” An ambitious list for a small encyclopedia, or even a full-length poetry collection. Nevertheless, in Animal Suicides Wong constructs an open space in which to explore the intersections and frictions amongst these topics.

Wong generates this open space, in part, through the formal qualities of her collection. She organizes her poems into short-lined, left-aligned, and single-stanza “chapters” of variable length that appear via two columns per page. Often, one chapter wraps from the bottom-left to the top-right of one page, or across multiple pages. While one could see this format as a way to save paper (i.e. two columns of poetry per page means this fits into 30-odd page chapbook format, rather than 60-odd page full-length book format), the performance of form on the page feels significant. While each poem/chapter is presented as short-lined, left-aligned, and single-stanza, in the way these chapters wrap and span the pages, Wong forces the reader to confront negative space as present, activated space, as space that defies categorization and explication, just as her speakers and characters move from human to non-human without pause.

Hence the first page, where, moving top-to-bottom on the page, the first lines readers encounter are not the first lines of the opening chapter, so they are not the first lines of the book. Or are they? With this, and many other elements of the text, Wong leaves the door ajar, generating multiple possibilities and loosing them onto this page. In this way, she echoes in form the content her book explores, as when “Chapter 21” opens, “quiet streets riot police / multiple gold / octopuses four deer.” Wong revels in accumulation for the sake of accumulation, the nonlinear and slippery play between streets and police, between octupuses and deer, where traditional methods of making meaning value are abandoned in favor of musical, evocative spaces that inspire more questions than they answer.

Similarly, while many chapters are titled via the word “Chapter” followed by a number in digit form (i.e. “Chapter 2”), Wong again thwarts reader expectations for predictability here. Thus, other titles transform this naming mechanism, leading to titles such as “Ch. Three,” “Ch 7,” “chapter then,” “20,” “Thirty-one,” and “Ch. Thirty 3,” among others, in a chapbook designed without page numbers. Further, several chapters dispense with this sequential pattern to offer nonlinear descriptive titles, such as “the open seas” and “the internet says.” Readers must use these chapter titles to reference their location within and way-finding of this collection, even as these titles defy consistent, dependable progression, possibly to heighten readers’ initial interest, or to destabilize more conventional, linear modes of meaning-making “in this revolutionary / world,” where,” the speaker declares, “we are / alternating.”

It follows then that each chapter inhabits a world governed by its own rules as to capitalization and punctuation (full-stop or otherwise). Animal Suicides begins with a succession of chapters lacking any punctuation — our first punctuation crashes onto the scene in “nine,” with:

The oceans are getting

louder — beaked

whales change their

dive patterns [. . .]

The dash after “louder” forces readers to linger, to notice the strength of voice and presence in the literal and figurative dash of the ocean, in what could be seen in other contexts as emptier space than the surrounding words. In this way, as we see with her titling choices, Wong edges toward exploring phenomenological theories of queer space as that which defies dominant patterns of linear progression, continual increase, and reproduction (i.e. spaces like the ocean or outer space). In Animal Suicides, more does not always equal better, as when, in this poem, the speaker realizes “noise / can kill” even as she knows “I need a noise / machine to sleep”. Or when, in “later,” “fifteen hundred / sheep walk off a cliff,” we see the risk of continued growth (and its corollary, overpopulation). Likewise, in “28,” the speaker recounts how two wildfires will “[have] sex to / make the largest / wildfire ever,” questioning whether this exponential growth is something “to be proud of” or something to “say no thank / you to,” leaving the question unanswered in the poem, both in content and in the lack of end-stop punctuation.

Continuing to consider the topography of Wong’s chapters, readers also must make meaning without mid-sentence punctuation from the first poem (“Chapter 2”), then surrender all punctuation until “chapter 6,” when we have sporadic mid-sentence and full-stop punctuation; returning to a space without punctuation until “nine,” where the dash of the ocean is the only punctuation across the entire poem. Capitalization and punctuation largely drop away from this point, for over 10 chapters, before returning and entering almost every poem. In this way, by the end of the chapbook, the occasional absence of punctuation and capitalization feels more remarkable than their presence, even though readers will have held the opposite view at the beginning of this brief collection. It is remarkable that Wong can unsettle and elide our convictions so quickly. Indeed, generating a space where absence and presence become intertwined and even dangerously interchangeable feels significant in this particular collection, which seeks to blur boundaries between animal and human, death and life, action and inaction.

As a performance artist and creative writer, Wong leverages her interdisciplinary skills to provoke and engage readers through juxtaposition and friction. Often, readers will be flung from a moment of suspension in beauty into a sudden graphic shock, and often in the space of a few lines. For example, in “why, part 2,” readers move into a strange and lovely lyric moment:

[. . .] whether

a half-moon or a salt-

cellar there is room for

storage an affair is

physics and angles

In this poem, Wong uses music and enjambment to evoke new relationships, making it possible for readers to consider resonances between the moon and salt, an affair and physics, and the potential space of a moon, a cellar, and psychology. Yet, just a few lines later, readers are thrown into the jarring final lines of this poem: “don’t kiss me i / will make my head / explode out my eyeball”. What an unexpected turn. Here, lyric beauty and narrative horror coexist in close proximity. Some readers might see in this juxtaposition a hint of Edmund Burke’s theory of the sublime, where beauty and terror coexist in nature; other readers, however, might wonder whether these irruptions of sex and violence after many otherwise beautiful moments might be an attempt to inculcate in the reader a critical and unsentimental attitude towards forms of violence otherwise obscured by the lyrical.

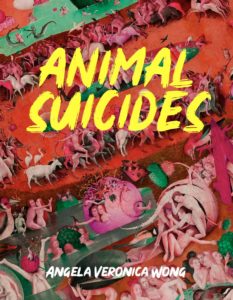

The friction across categories is evoked by the collection’s title — Animal Suicides, joining the animal kingdom with the more human phenomenon of suicide — as well as its cover art, which Wong helped to curate. In bold hues of electric green, pink/red, and yellow, the cover shocks the potential reader and confronts them with an assemblage of figures without clear boundaries, where nude humans transform into a sea creature, open their mouth for a berry larger than their head, or house a red ball erupting in birds and foliage between their legs. Here, the border between human and animal becomes unclear, encouraging readers to re-examine the collection’s title and the implicit assumption that ‘humans’ are separate from ‘animals.’

Thus, in Animal Suicides, Wong explores how can we embrace our animality even as we recognize our fundamental detachment from the environment due to our tech-driven humanity. In “22,” Wong writes of an orca whale who “keeps her baby / whale’s body afloat for / two weeks,” slipping immediately into “just get over it,” a phrase often pushed upon grieving humans that acquires new significance here. Thus, a few lines later, Wong shares:

we congratulate our

ability to notice

humans don’t have a

monopoly on grief [. . .]

As per the title of this collection, Wong’s poems regularly explore death and suicide in an animal kingdom that blurs and bleeds over into the human world, destabilizing boundaries and truths.

Wong’s ambitious catalogue of themes, paired with shifting formal patterns, could make this chapbook feel more scattered than generative. Even so, Animal Suicides demonstrates an impressive reach. It is a rare book that can hold a poem that lists the process by which several species’ young consume their mothers (“Thirty-one”) adjacent to a poem that explores birth control, stalking, and the etiquette of Tinder (“Chapter 30”), even if this dialectic between old and new, human and non-human, birth and death begins to feel a bit expected as the collection progresses. More uniquely, Wong offers a rare book that can simultaneously anthropomorphize to enact cultural work toward inclusion, as in “Chapter 18,” where:

bryan is a 27-year-old

giraffe who thinks

women are human

beings i see him [. . .]

And, moments later, can critique the limitations of this very process, as in “Ch. 29,” which opens with the speaker declaring:

Don’t

anthropomorphize the

animals I warn Chip

even as we coo at the

video of the cute

raccoon [. . .]

Just as the speaker of these poems can push readers toward the harder truths of considering their roles in our current environmental crisis, this speaker is also willing to admit her own complicity in the crisis alongside us. In this sociopolitical moment of environmental degradation and the recall of environmental protections (along with basic rights for freedoms of speech and identity), it feels vital to write and read texts unafraid to provoke, question, and challenge both ourselves and our communities. Whatever else one can say about Animal Suicides, one must admit it is not a quiet, meek, nor uncontroversial book. Though the collection could be stronger with a tighter focus and a larger format, Wong still gives us a book able to unsettle and spark conversation about the environment, death, truth, responsibility, and the nature of identity.

Wong closes her chapbook with a memory of “another time / when I found a trash / can for my waste,” where waste was still tangible and limited enough to be confined. Here, now, thresholds blur, and we must confront our presence in our absence, our environmental impact across even the most intimate parts of our lives. Animal Suicides takes risks to pursue these themes, leaving readers in a state of unsettled wonder and curiosity — an openful state we could all learn from and use more of right now.

Lucien Darjeun Meadows is a writer of English, German, and Cherokee ancestry born and raised in the Appalachian Mountains. An AWP Intro Journals Project winner, Lucien has received fellowships and awards from the Academy of American Poets, American Alliance of Museums, Colorado Creative Industries, National Association for Interpretation, and University of Denver, where he is working toward his PhD.

This post may contain affiliate links.