Jeff Alessandrelli: What draws me to Chyrum Lambert‘s art is its multiplicity: titles that are poems and sculptures and paintings that vividly exist in the physical world and later even more vividly in the viewer’s mind’s eye as they walk the sun-dappled or rain-harried blocks of sidewalk and street. When I was on Instagram last year for a short 45 days before wholesale quitting (failure/success), Chyrum’s handle was the one I frequented the most; his own work is displayed, sure, but also the work of dozens of other visual artists, writers, and thinkers generally. It was and is its own art history course. When the opportunity for this conversation came up I was excited to ask Chyrum about being a self-taught artist, titling his work, and compensatory artistic acts, among other far-flung topics.

Chyrum Lambert: I first came across Jeff Alessandrelli’s work at a bookstore in Portland, Oregon. His book, THIS LAST TIME WILL BE THE FIRST, jumped out at me due to its hopeful yet paradoxical title. Now it’s one of a handful of poetry books I keep in the studio that I’ll frequently reference when making decisions during studio work. As an artist it serves me as a trigger, and that’s a quality I find especially attractive in any work, the ability to direct my attention “over there,” a type of focus refresher from routine patterns of work or from the rituals of daily thought. His follow-up, Fur Not Light, feels more personal, with an attraction to aging and a focus on the person we think we are becoming. Also intriguing is the book’s numerous sections resembling chapters or titles. The individual poems build nicely within these structures but also in relationship to the distinct sections or series – they appear to be speaking to each other. I was happy to have this conversation with Jeff.

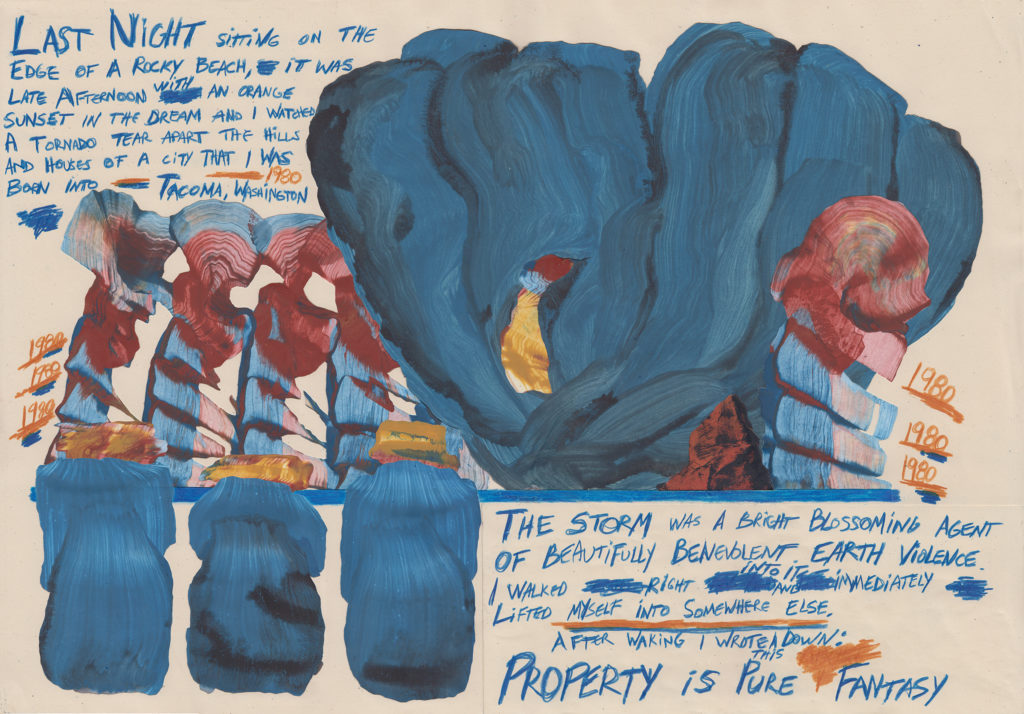

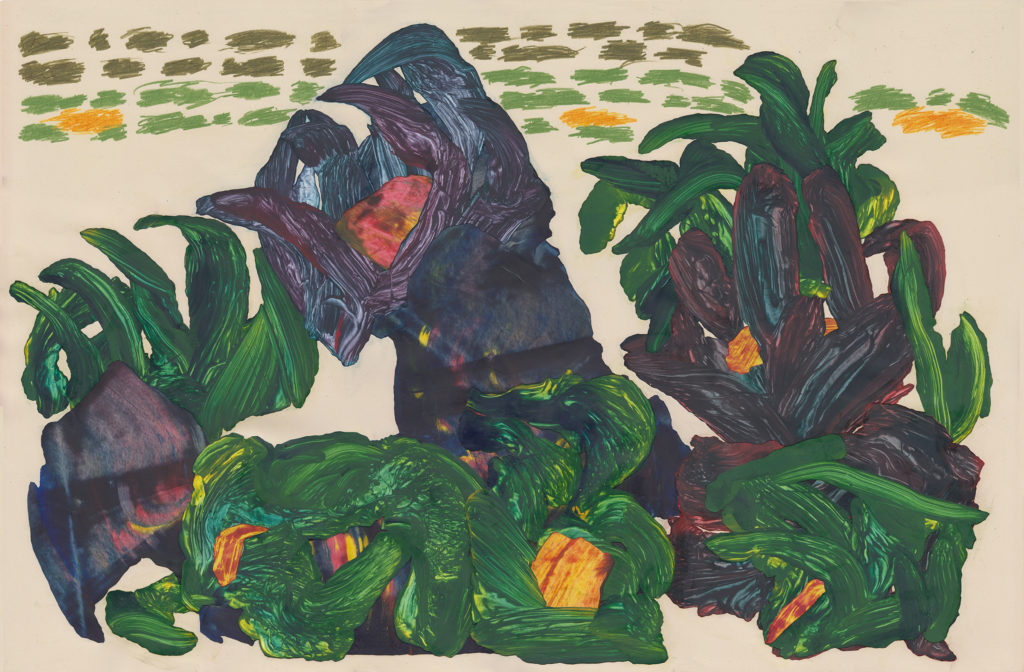

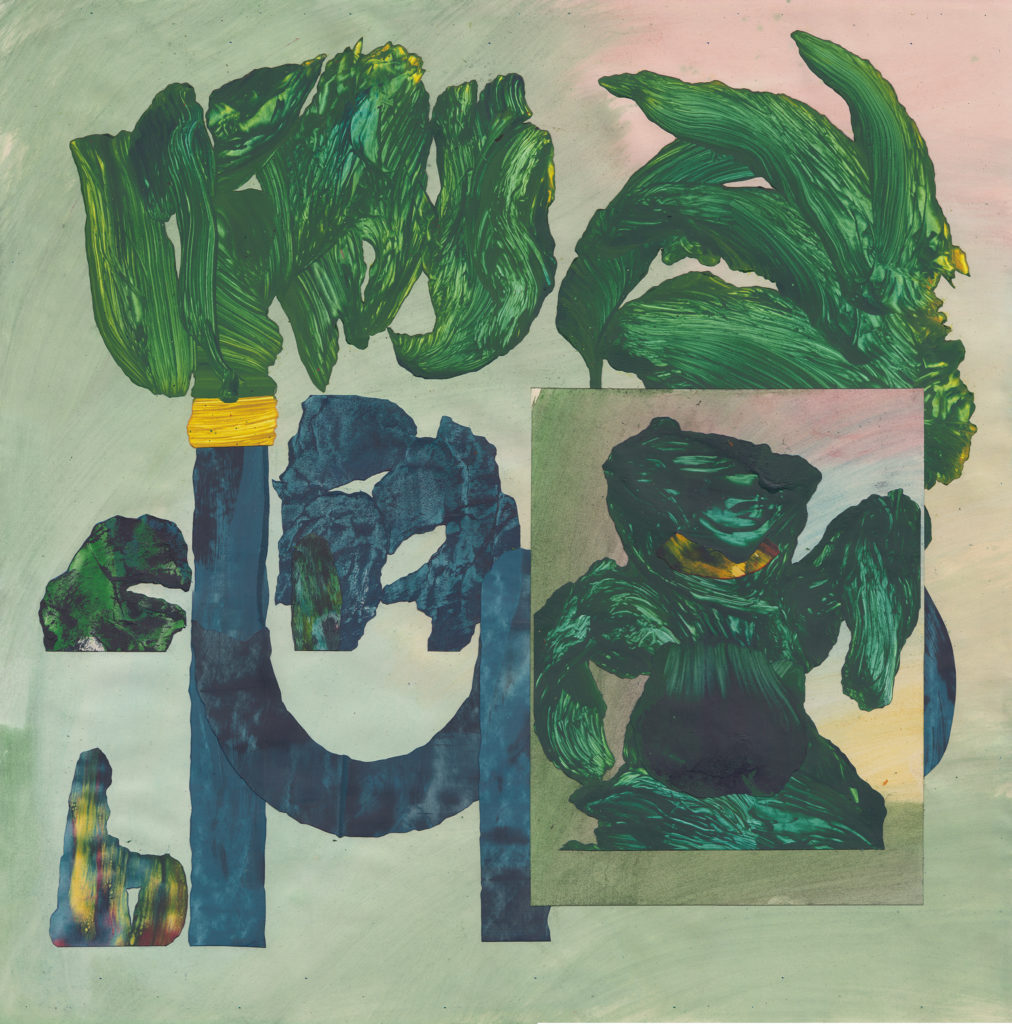

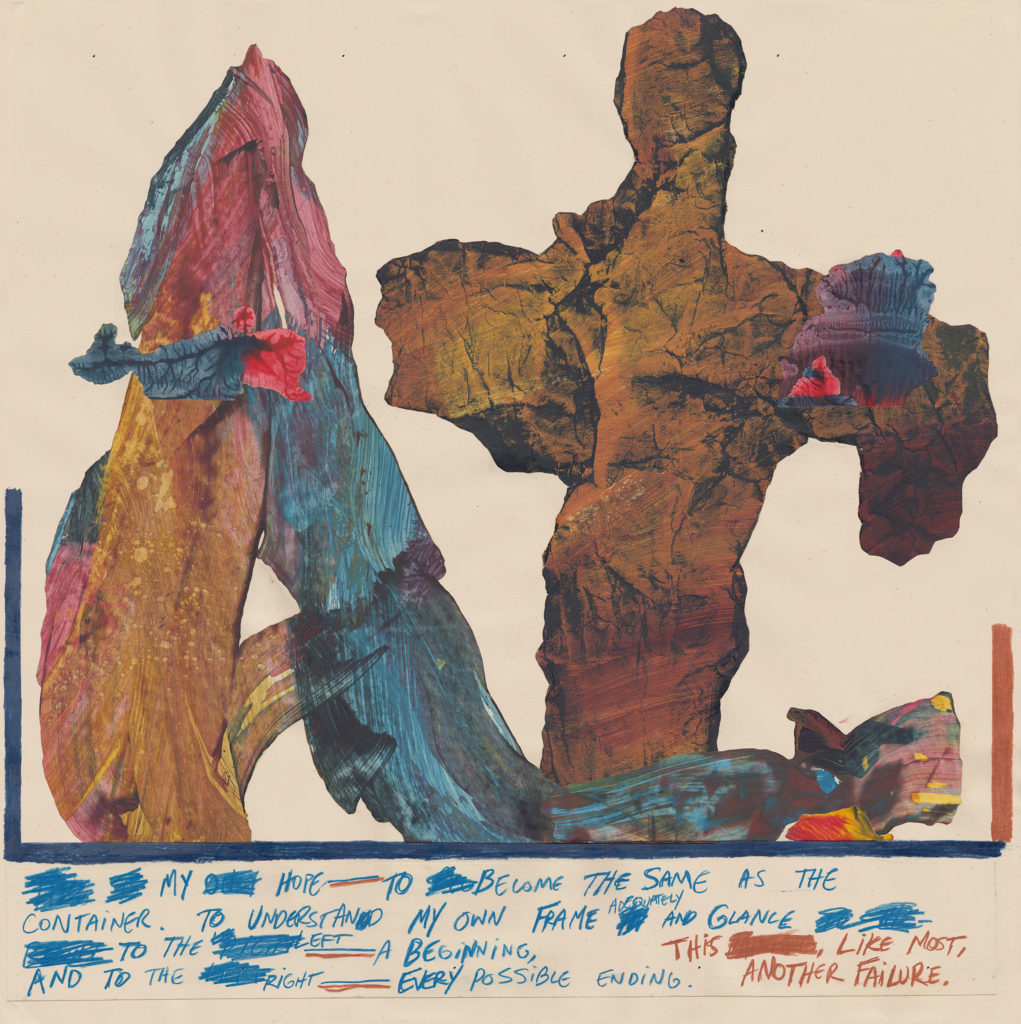

[Editors Note: The following images are all by Chyrum Lambert]

I wanted to begin with a basic lob, but one that I think is important. You’re a visual artist. You conceptualize “stuff” in your “mind’s eye” and then make it. As an imagemaker, then, how important is language to your work? I’m particularly interested in some of the titles of your pieces – “An Eye— Symbol Of Envy And Love, Glance Of A California King Or Hiss Of A Rattlers Fork— Function Of A Forever Fever Fueled Piston Of Staring Face— What You See Now Is The Image Of A Snake” – comes to mind, among many others. So language. What role does it play in your often wordless works of art?

This is something I’m guessing we both think about often. My own use of language as a tool in my image-making exists because I think my understanding of language is stronger than the understanding I have of my image-making and because of that it seems a much easier tool to wield. I also just like how accessible a word is. I like the way a word can immediately be grasped by anyone because it can only be abstracted by the relation it has to another word in a sentence or phrase. A different handwriting doesn’t necessarily change the way you feel about the specific word. The word “tree” handwritten by you or me or someone else would generally elicit the same response. But with an image every unique drawing of a tree will slightly affect your recognition and understanding of that tree. That’s what I find interesting about words, that they are really a delivery service for singular concepts. This of course changes when you talk about poetry, but in its most basic form I love its simplicity.

So I prefer to lean on language in a way to direct the viewer’s attention and to counteract deficiencies I see in the paintings. Most of my paintings have well delineated images and shapes but still have a great deal of ambiguity in them, so when I add in a title it really confuses and completes the image. I think it opens up more questions and can help establish a sense of drama. Sometimes I’ll place the text within the image, sometimes it’s given through the title. Now this crossover of the two mediums, the action of providing text alongside an image is really just protocol for making paintings or sculptures, because you’re expected to title them and document these things with words. With poetry it’s a bit different because you’re usually using the same system that the poem is written within to title or to document the poem. Although in your new book Fur Not Light I’ve noticed instances of you fitting in images, emoji’s, or, as in the final poem of the book, a series of black lines crossing out a great deal of the words, leaving (to great effect) the remains of an uneasy speaker. What relationship do you have as a writer with imagery as it relates to language? Or language as it relates to imagery?

For me – and I think this is true of a lot of writers – my “inspiration” comes as much from visual artists as it does from writers. I think what you noted about different handwriting is both the beauty and challenge of language: using the exact same word, four identical letters, how can a writer make their own tree different from every other one? It’s impossible and yet still a primary goal: to separate one’s own limbs and branches from the billions of trees and attendant forests that have been written before.

But to my own relationship with image as a writer – like a lot of poets I’m interested in ekphrasis and how what we see determines and/or shapes both who we are and how we write. But it goes deeper as well. My sister is a graphic designer and visual artist. Growing up in my childhood home her paintings hung in my parents’ garage and I think their shadow still impacts me. I can’t draw to save my life – my stick figures are far more stick than figure – so from a young age being around artistic form and representation that I knew was impossible for me to personally achieve played a great (if subconscious) role in my being a poet. In her book 300 Arguments the writer Sarah Manguso states: “A great photographer insists on writing poems. A brilliant essayist insists on writing novels. A singer with a voice like an angel insists on singing only her own, terrible songs. So when people tell me I should try to write this or that thing I don’t want to write, I know what they mean.”

Reading that rang true with me, in that I do think so many writers are engaging in compensatory acts for what they can’t do . . . I can’t make images visually, of my own wholesale creation, so instead I try and make them with language. Sometimes those images are made to be clear-cut; other times – as you mention in the final poem of Fur Not Light, where the majority of the lines are crossed out – they’re meant to be ambiguous or absurd, unsettling.

A segue but hopefully a fairly natural one – your website lists you as a “self-taught artist living and working in Los Angeles.” If self-taught means that you didn’t go to school for your artistic craft this brings up a major difference between us. I hid out in school for a decade plus, refusing to enter the “real world” for the benign security of academia. Can I ask how you feel about being self-taught and how you think it has affected your own art making? Although it also showcases your work, your Instagram feed is essentially a compendium of literary and art history outtakes and snapshots, so you’re obviously fully engaged with and aware of the framework of artistic culture both now and then. If I personally had to do it all over again I don’t know if I would have done it the same way . . . being taught about one’s passions in set intervals of time in fluorescently lit rooms with plastic tables and chairs changes things, especially if, like me, you start showing up in those rooms at a young age. Was your experience in artistic discovery completely different from my own?

My approach to the arts is almost the opposite reaction in that I’ve always specifically chosen things that seemed a bit out of reach from what I’ve been previously capable of. A big part of my creative work has always been attached to ideas of personal growth or development. And the only way I can really stay interested in my work is by continually expanding it into areas or mediums I’m a bit unsure of. It’s really driven by the pleasure that those activities afford me. And I think that this may have something to do with having no formal education. For me art has always been a curiosity-driven personal study, where the goal is the activity itself. This has had advantages in that the work has mostly been generated outwards through its own growth, or its own diet. Art/poetry is also extremely self-referential, so it’s a simple thing to go from one reference to the next. The artists or writers you’re reading become the teachers.

Now whether there is any commodifiable or critical value in what I am doing has never been an important question for me. But perhaps I would see this differently if I would’ve attended university like you did? I can’t help but think I would have left academia expecting to get something out of all of those years of study, whether it be a job, gallery interest, or some kind of praise. Being that it is an education gained through an exchange of money, how could we not expect something in return from our education, especially being born and raised within a capitalist system? This is the trick, and the question, because art is independent from such systems. So how do we make art as if that capitalist system isn’t lingering over all the work in the studio or the notebook? I think the answer is maybe not pretending it’s not there but instead openly acknowledging its oppression.

Keep in mind I’m saying this having spent zero time in academic study, so this could be an excuse I’ve tricked myself into to make me feel better about my decision to forgo a college education. The downside of being self-taught is that you’re really going at it alone. So I’ve always been envious of the community that academia affords you, and the access and interaction to wide ranging contemporary thoughts/ideas/criticisms and such.

Interesting to me that you see your writing as a compensatory act. Having read several of your books, it’s hard for me to see this. Regardless of your inability as a visual artist, though, you must have had an attraction to writing in some way, right? This is also interesting to me because the section “Resignation Modes” from your new book is a series of poems dealing with this very idea; the various speakers discuss the conscious and subconscious ways of resignation that everyone deals with, oftentimes without even realizing it. It’s a straightforward long poem, and the part of your book that had the strongest effect on me. It made me think a bit more about my own actions and realizing how close and confused the act of resigning oneself is with the act of compromise. Do you feel as though you’ve resigned yourself to poetry?

You’re right – I’ve always had an attraction to writing, but, à la the above Manguso excerpt, it’s certainly something that I’ve repudiated on a number of different occasions – if only I’d been a musician or visual artist, etc., etc. And although I know I could and to a certain degree have dabbled in both of those mediums, I’ve never been interested in being a Renaissance person . . . I’d rather stick with what I know, relearning it over and over again until I don’t know it anymore and have to freshly relearn it.

Thank you for saying that about “Resignation Modes.” I don’t feel like I’ve resigned myself to poetry, not because I regularly write in other genres, but more because I do think the poetic form is essentially inexhaustible. Even though I just used it, genre is such a flimsy word – I was going to write circa 2019, but I think it’s been that way forever, or nearly – and a poem can be so many different things or forms, tones or sounds or styles.

With “Resignation Modes” I do suppose I was getting at the nature of subconscious resignation generally, from a variety of different angled sides. Artistic resignation to a degree but also just resignation generally, in the way that I’ve personally resigned myself to the fact that my 12 year old, 90 lb. dog Beckett (who I love with all my heart) will always pull on his leash because I never taught him not to, or, more seriously, how due to my predilection for certain substances I’ve been forced to resign myself to never partaking of them anymore, even though I’d verily like to.

“The meaning of life is that it stops” is how Franz Kafka once put it and I guess that’s the ultimate resignation, but for me such a declaration also – as in much of Kafka’s work – contains an implicit hope. If the only meaning of life is death and, whether we like it or not, we’re forced to resign ourselves to that prospect, then we also have to resign ourselves to eking as much enjoyment and gratitude out of life as possible. Although “Resignation Modes” was started in a not so positive place in 2017, I do think by the end of it there’s a glimmering of sun. As I’ve gotten older, I personally have worked on resigning myself to positivity and gratefulness and, even if it’s sometimes exceptionally difficult, hope.

In a way this ties in with your transparent positioning of capitalism’s oppressive nature. I think the trick is to be fully aware of that oppression, to acknowledge it and consider its calculations, but to also challenge oneself to exist in a framework beyond it, where what’s being created is more important than where it’s shown or read. (Or not shown and not read.) That’s an easy thing to write and a much harder thing to do, I know – through our screens and in our heads and bodies, we live in all this stuff, and it’s impossible to turn it off. But if for short intervals of time we’re able to do so I think our creations might end up all the better.

To end, I wanted to ask about your latest exhibition My Usual Line And Shape Is A Line. In the online catalog you write, “on occasion of this show, I pulled apart my studio to discover the past work I’ve made much more in the present than I am. And my hypothesis now, upon uncovering this thought is this: that the past and any allusions of change are necessary allusions needed to better accommodate any personal ideas of progression or development. In more comfortable terms, it’s about time to see time sitting beside itself. Not forward or backward, or better or worse, but as the same thing.”

This immediately struck me, because so much of artmaking seems concerned with (capitalist?) progression – we are (or should be) “better” artists now than we were 5 or 10 years ago, etc. But it seems to me that you’re openly saying that such a postulation is nonsense; “time sitting beside itself” contains no value judgments and what we learn today can be forgotten – or misunderstood – tomorrow, in both helpful and harmful ways. Am I reading that right? And was the process of putting all that work together an art-affirming beginning and end for you as an artist?

There is a hopeful resignation to those poems and maybe by saying you’ve resigned yourself to positivity and gratefulness implies that there’s a predisposition to negativity? I find this really interesting because I think it’s something that we continually ask ourselves as we get older. And particularly with artists because we have all of these remains (the work) that we’ve made. This continual re-evaluation of ourselves and what we have done with all the past hours of our lives. Maybe after so many years I’ll resign myself to the pattern that emerges from my personal past reviews and self criticisms. Maybe it will tell me what I’m good at as opposed to what I find interesting. I’d like the think they’re the same thing but I’m really not so sure.

And as far as your question, yes, I think it’s nonsense to believe that the work we make is always getting better. I see it more as a change in perspective as we age and engage in new experiences. There’s a naive freshness and boldness to earlier work that only exists because of the excitement of first encountering and putting those materials together. But it only looks bold and fresh to me because of my relation to it. Time has moved away from it and that distance gives me space to now critically assess what I’ve made. And this is happening all the time. Right now we’re encountering something new and five years from now I’ll be looking at them the same way I currently do with “old” work from 2014.I’ve attempted before to remake work I’ve done in the past because you tend to think, I myself made this thing, so I should be able to do it again, but really that’s an impossibility. Art just doesn’t work that way. There’s that phrase from Heraclitus, “One cannot step twice into the same river, for the water in which you previously stepped has flowed on.” So my concerns as a painter are really the same as they were years ago; I’m just stepping in at different points in the river.

I’ve read two books of yours now,THIS LAST TIME WILL BE THE FIRST from 2014 and 2019’s Fur Not Light, and I don’t know you personally so I don’t have any insight into your person/process beyond that work and this conversation, but your books feel like they’re both the same writer. To me there’s an overarching theme and concern for how an individual can exist within certain social frameworks. This is, of course, dressed up in a variety of ways and poeticisms, but how do you feel about the connections between the books you’ve written? Do you see it as a process of getting better at communicating through your writing? A stronger clarity of thought?

Although it isn’t my best trait, I would definitely say I have a predisposition to jadedness, cynicism and, yes, negativity. In different periods of my life, sometimes for very long stretches, I’ve lamented my circumstances: if only I had done this or said that, etc., etc. But the easiest thing to do is complain and complaints normally land nowhere, do nothing. Although it seems like there’s more strife in the world every waking moment, I’ve resigned myself, as I said earlier, to believing in positive change and through my own small actions I’m trying to make that happen. Sometimes I fail but then I wake up and it’s tomorrow and I endeavor to try once again. Hope’s an eternal process but it’s one I’m intent on continuing.

Your own concerns regarding the distillation of artistic perspective with the passing of time intrigues me too, if only because it’s often hard for me to see myself in any of my work. Meaning that although concepts like “voice” and “style” are constantly bandied about in writing, I personally don’t see much of a throughline in terms of my own work. Although I can access the eagerness and low-key drive in THIS LAST TIME WILL BE THE FIRST, it’s really hard for me to imagine writing those poems again, or to conceive that I wrote them at all. (Most were written between 2010–2012.) Same with certain parts of Fur Not Light, which began in earnest in 2014, but took many shapes and guises. What’s in the world now isn’t the same collection that I initially began writing. So the river might be the same but not only am I at a different point in it, my feet have also grown both bigger and smaller, and my relationship to the water flowing in front of me has similarly expanded and constricted in some fundamental sense.

With that being said, I do feel a stronger clarity of thought as I’ve grown older, although I’m not sure it’s an artistic clarity. It’s more of the variety that, day in, day out, I accept what I can’t control and try to be cognizant of that acceptance. Failure or success can only be defined by the individual artist, and that fact is one I hold close nowadays. Within that knowledge lies the ultimate connection in what I’ve written over the years.

Chyrum Lambert (b. 1980, Tacoma, WA) is a self-taught artist living and working in Los Angeles, CA. Internationally published and exhibited, Chyrum has shown at Palazzo Monti, Italy; Underdonk, New York; DTN Gallery, New York; Ed. Varie, New York; Left Field, San Luis Obispo; Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles; Hashimoto Contemporary, San Francisco; Independent Art Book Fair New York and Untitled Miami Beach Art Fairs among others. Lambert’s work has recently been published in and/or written about in New American Paintings; Artsy; The Wild Magazine; Parcel Magazine; Juxtapoz Magazine; The Last Magazine; Sight Unseen; It’s Nice That; and Paper Magazine.

Jeff Alessandrelli is the author of the full-length poetry collections THIS LAST TIME WILL BE THE FIRST (2014) and Fur Not Light (2019), both from Burnside Review Press. He’s additionally the author of a short poetic biography of the French avant-garde composer Erik Satie entitled Erik Satie Watusies His Way Into Sound (Ravenna Press; 2011), a short essay collection focusing on skateboarding and The Notorious B.I.G. entitled The Man on High—Essays On Skateboarding, Hip-Hop, Poetry and The Notorious B.I.G. (Eyewear (U.K); 2018) and five chapbooks. Recent work by him appears in Poetry Northwest, The American Poetry Review, and The Hong Kong Review of Books. In addition to his own writing, Jeff also runs the vinyl-record literary label Fonograf Editions. He lives in Portland, OR.

This post may contain affiliate links.