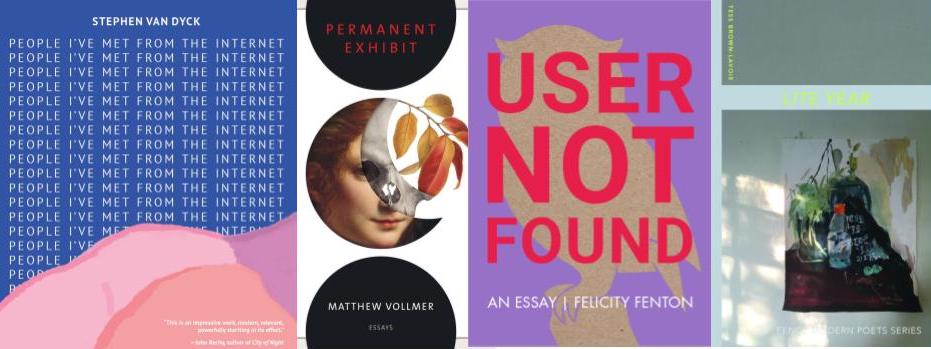

The internet is trending again in this year’s catalogue of new and forthcoming books, three decades after it boomed into commercial use in the mid 1990s. After an initial spate of writing on the hub of internet connection, of Facebook and Twitter, of looming fears on tech takeovers, the motif of online connectivity seemed to have died down. And yet this upcoming slate of small press books, including Matthew Vollmer’s Permanent Exhibit (BOA Editions), Tess Brown-Lavoie’s Lite Year (Fence Books), Felicity Fenton’s User Not Found (Future Tense Books), and Stephen Van Dyck’s People I’ve Met From the Internet (Ricochet Editions) has turned back to it. Why now? After all this time, with the internet becoming a more and more commonplace part of everyday life, why is writing about living online trending again?

Social media was meant to be the bridge of connection, but in the early days of Web 2.0 there was a terrifying omen of perpetual contact, and the dominant discourse foreshadowed long-term mental health problems centered on the effects of constantly performing for our peers. It seemed like for years the digital age loomed over everyone’s heads as something simultaneously rocketing us into a better future and damning us into a terminator apocalypse of robots — Schrodinger’s Internet could only be determined by years in the digisphere.

Many remember MIT Professor Sherry Turkle as one of the most vocal commentators on the social effects of living online, with her book Alone Together in 2011 (Basic Books) and then later Reclaiming Conversation in 2015 (Penguin Books). She contributed that as technological relation ramped up, authentic relation declined — but who was to say what connections were genuine? She starts her TEDxED Talk describing her daughter’s messages: “Getting that text was like getting a hug.” She then continues to warn that this relationship to our media, our constant closeness, was not genuine closeness. “People want to be together,” she says, “but also elsewhere.”

This thesis was my earliest memory from my first year in undergrad. All new students were assigned Turkle’s book Reclaiming Conversation in hopes that we’d relearn how to communicate. We logged onto our online portals to write blog posts about how technology hindered our ability to connect, really connect with our peers. At that point, none of us knew each other, and Turkle’s thesis seemed, we begrudgingly admitted, melodramatic but possible. We turned on hotspots and added every person simultaneously on Snapchat, our way of introduction. Was Sherry wrong, then? To our knowledge, social media had given us everything — our friendships, our long-distance hope, our reputations, seemingly most of our endorphins. To think it was the very thing stunting our emotional maturity, when we knew it was our first introduction to a larger concept of the world, was confusing, and caused a large pushback between students and professors.

Generations felt split. Those newly exposed to the internet maintained a foresight of wariness, knowing what it was like to live without being permanently online, whereas those like me who grew up with it embraced social media as a means to an end. LinkedIn gave us jobs, Facebook gave us friends, Twitter gave us platforms to reach to anyone — to start protests, to speak to government officials. Social media launched careers and just as quickly tore them down. As this younger generation grew, it appeared the warning signs died for much of the 2010s. The idea of a perilous digital age was old news.

The cusp of Millennial and Gen Z, people who grew up with the internet as an essential normality, are entering or preparing to enter the workforce, and they are quickly becoming an even larger insurgent for a tech-friendly work environment. They are immersing themselves in positions of power, and the need to write about it persists. These two radically different perspectives on the internet, as a tool or as a warning, are meeting, sometimes colliding, sometimes collaborating, but they could not be more different. And so, while it’s true that the digital age might be old news, many people finally have the platform to discuss what a different experience they had with it — in a more nuanced and lived perspective. This generation gets to use their authority to embrace a new methodology to engaging with the internet, and the takes are varied but overly fixated.

For example, Matthew Vollmer’s poetry collection Permanent Exhibit (BOA Editions) follows the immediacy that social media has to offer. Vollmer “opens a browser window into his own mind” in “the age of the status update.” What does it mean in poetry to co-opt the internet’s constant sense of connection? Here it takes the form of stream of consciousness, not unlike a streaming feed or timeline, where subjects revolve in and out in dizzying continuity. Connectivity is no stranger to writing, and yet never like this, from the lens of something so pervasive in our world. With it, we get new revelations — not just how is life in the digital age, with a numbing news feed of emojis, mass shootings, and pop culture, but what does the digital age reveal about and through ourselves? The internet becomes a rabbit hole of metaphorical and literal searches, and we do not always find our answers.

Similarly, Lite Year by Tess Brown-Lavoie (Fence Books) explores the concept of the digital age through poetry. And yet, her take both dichotomizes and integrates the life of a young farmer within this world of tech. It is described as “contemporary” and “epistolary,” and the narrative element of letter-writing vaguely reminds us of personal writing in the digital age, an open journal. And yet here, the addressee is known, through distance, in need of contact. Again, the common soil here is connectivity. Lite Year has never been a measure of time, but of distance in a digital atmosphere.

User Not Found by Felicity Fenton (Future Tense Books) and People I’ve Met From the Internet by Stephen van Dyck (Ricochet Books) both help situate how we look back on digital upbringings. Both describe a sequence of interactions on the internet, but in radically different perspectives. Fenton attempts to untangle herself from any online box, calling social media “the walls” and meditating on the darkly humorous attachment to online connection. With the merging of the internet into daily survival comes the alternative problem of removing oneself from it. Is living possible outside of this world? The rabbit hole of answers is not always a good thing, and Fenton does not shy away from those perils.

Van Dyck, on the other hand, spans twelve years on the internet in his nonfiction piece, described as “a queer reimagining of the coming-of-age narrative set at the dawn of the internet era.” A benefit to writing about the dawn of the internet age from a comfortable distance is the ability to see it for what it was, and how it helped us and took us down — for many, the internet proposed the possibility of a hundred lives, many “utopian” in nature, an opportunity to connect to the world digitally in ways we could not literally.

No one at the start of the internet era could have predicted the impact it would have on seemingly concrete narratives like that of the coming of age. Everything inside the lens of the digital world is altered, revolutionized. Growing up in the age of the internet has meant seeing my life narrative as part of a macrocosm of such stories. And while at times the easy exposure of social media was something to warn about, something to distance from in fear such as Fenton discusses, it can also make it possible to situate yourself in a world that you couldn’t previously find a place in. The internet, while macrocosmic, is also niche, varied, impossibly overlapped.

We have never been further from our upbringings. The internet, much like those who were introduced to it, has grown, and despite the vastly different people who inhabit the tech landscape, the experiences and effects of connectivity have increasingly (and increasingly unremarkably) permeated our lives and literature. We are no longer discussing so much the possibilities of what the digital age could do, but of what it has already fixated inside of us.

Allison O’Keefe is an English Literature and Creative Writing student at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts. She is a co-managing editor of MCLA’s literary journal Spires, and has had poetry published in the 2018 and 2019 editions. She is an Operations Administrator at Tupelo Press and a PR and Member Relations Manager at the Cape Cod Discovery Museum. She is studying to become a 2020 Massachusetts Commonwealth Scholar.

This post may contain affiliate links.