[New York Review of Books; 2019]

[New York Review of Books; 2019]

In the opening paragraph of his 1965 novel Stoner, John Williams crafts a taut, quiet outline of the life of William Stoner, his eponymous protagonist who can also best be described as taut and quiet (closer to a barely audible whisper). It renders the substance of the novel to come down to a brief accumulation of unremarkable facts and dates:

Williams Stoner entered the University of Missouri as a freshman in the year 1910, at the age of nineteen. Eight years later, during the height of World War I, he received his Doctor of Philosophy degree and accepted an instructorship at the same University, where he taught until his death in 1956. He did not rise above the rank of assistant professor, and few students remembered him with any sharpness after they had taken his courses. When he died his colleagues made a memorial contribution of a medieval manuscript to the University library. This manuscript may still be found in the Rare Books Collection, bearing the inscription: “Presented to the Library of the University of Missouri, in memory of William Stoner, Department of English. By his colleagues.”

What remains utterly remarkable about Stoner revealing its hand here at the outset is the novel’s insistence on not deviating from this narrative path, refusing to allow William Stoner to exist internally as an extraordinary character who has somehow been cosmically denied his fair tribute. William Stoner’s ordinariness reads as neither allegory nor tragedy; instead, Williams crafts this fictive biography in the mode of a minor key naturalism, excising existential quandary for the inevitability of disappointments, an accumulation of stress fractures that never fully morph into the pathos of heartbreak or the bathos of a grandiose fall from grace.

William Stoner’s life revolves around the printed word and the libidinal attachments entombed therein. Stoner’s own memorialization remains bound to libraries, both the exhaustive breadth of the university collection in which his name remains inscribed on that medieval manuscript and his own personal library, that personal collection Walter Benjamin refers to as “the chaos of memories,” the accumulated matter of a lifelong scholar. William Stoner dies clutching his own (and lone to published) monograph: “It hardly mattered to him that the book was forgotten and that it served no use; and the question of its worth at any time seemed almost trivial. He did not have the illusion that he would find himself there, in that fading print; and yet, he knew, a small part of him that he could not deny was there, and would be there.” William Stoner clings at the moment of his death to the possibility of an afterlife on the page, one in which his own particular ordinariness can remain indissoluble from the general whole of the ordered catalogue: “He opened the book; and as he did so it became not his own.”

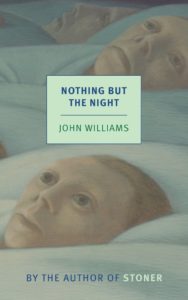

When the reprinting of Stoner led to a renewed critical and commercial attention more than a decade ago, John Williams himself seemed to have been revived from the doldrums of those forgotten shelves. 1960’s Butcher’s Crossing and 1972’s Augustus both subsequently found reprints and renewed circulation through the NYRB Classic imprint. The last of Williams’s novels to be reissued, the first he ever wrote, 1948’s Nothing but the Night now marks the inevitable death knell of the Williams literary revival, the moment in which nothing more remains to be dredged up and brought back to our collective attention.

Nothing but the Night demonstrates that in the chaos of memories bound up in the collection as such, some items have been deservedly forgotten. As most folks who have spent time in a library collection know, if you peruse down the shelves of the great unread, some have been unread with good reason, works dead even before their moment of arrival because nothing much (if anything) had ever lived within them.

Written at twenty-two years old while in Burma amidst his military service during the Second World War, Williams’s initial foray into writing strongly bears the traces of the hastened first attempt, the labor of its composition highly evident in its overwrought attempts at a weighty existentialism. The novel takes place in the course of a single day (this very schema recalling the twin pinnacles of high modernism with which this work will disharmoniously resonate) in the life of Arthur Maxley, a wealthy college dropout holed up in a metropolitan hotel whose penchant for drink is supposed to alert the reader unfamiliar with cliché that something troubling (and most likely repressed) lies just beneath the surface.

The novel’s highpoint comes in its first pages, prior to our introduction to Arthur proper, in a dream sequence, a brief moment wherein the novel’s evocation of psychological horror lands: “But the peculiar circumstance of dreaming is that the dreamer is bereft of power…He is the tool of a dark prankster, a grim little joker who creates worlds within world, lives within life, brains within brain. All of his illusionary power comes from this gleeful scenarist whose whim it is to bestow and withdraw.” In the midst of the dream, the dreamer cannot initially recognize “the small pale figure in the too-large chair” who appears entirely out of place, ghostly, “a noise without meaning, an explosion without disruption.” Of course, however, the dreamer has merely been granted one of the momentary surrealities of the dream itself, the ability to see himself at a remove, to play act for a time as a disembodied narrator. Once the dream ends and Arthur Maxley awakes, the novel never recovers.

Those narrative departures (often provided via vivid flashbacks) become weakened through their inability to flesh out a character who is not only horrid but also impossibly flat. Looking about his room, Arthur’s self-loathing thoughts merely register as prose desperately straining towards gravitas: “The room is like my soul, he thought. Dirty and disarranged. He smiled. The hell it is, he told himself. It is a room and the maid will clean it up this morning, as s he cannot clean up your soul. Who is there to clean up your soul?” This form of childish, snobbish angst could perhaps work if it was tempered in an ironic mode, calling attention to the sheer humor in its overwrought formulation; instead, it continues to pile on. Arthur Maxley seems distraught, but the novel’s insistence on keeping us waiting for the big reveal leaves us stranded with a wealthy young man who hates his father and seems lost without his absent mother (an Oedipal structure as heavy handed as that “dirty soul”). Maxley becomes angered when he orders “one cup of coffee and one egg — no toast — and a bottle of Tabasco sauce,” because the waitress at the diner does not register what an intriguing breakfast palate he has. Later as Arthur waits on a companion for lunch he has another one of his interminable revelations: “In the long run, he thought, that is all one does; wait for people or keep people waiting.” Then at lunch, with the lone person who can seemingly stomach his company, Arthur Maxley reveals another layer of his despicableness — homophobia: “It was not friendship; no one could feel friendship for [Stafford]. He had no sympathy for the sort of person Stafford was. Stafford’s particular perversion constantly repelled him, and there were times when he felt active dislike, even spite, for him.”

It should come as no surprise then, that the novel’s climactic reveal attempts to elucidate the prior trauma that has necessarily led to Arthur possessing ever so many detestable qualities: Arthur witnessed his mother shoot Arthur’s father and subsequently commit suicide. We never receive any explanation as for why this event occurred, but of course in a novel steeped in the psychoanalytic register, the repressed returns. After Arthur meets an intoxicated woman at a club, he returns with her to her apartment, brutally hits her whereupon a neighbor intervenes, and he remains upset and pouty that she cannot understand why he feels his violent outburst was a necessary one. Finally, he walks off “down the long narrow street toward where the darkness converged and there was no light, where the night pressed in upon him, where nothing waited for him, where he was, at last, alone.”

If William Stoner is an utterly forgettable man portrayed in an unforgettable piece of prose, Arthur Maxley and the novel which invites us to know him are both far too memorable for all the wrong reasons. Nothing but the Night exists as little more than a curio on the shelf, a novel that shares only an author’s name in common with Williams’s mature works he would go on to produce. Unlike William Stoner, Arthur Maxley always deserved the anonymity of history’s dustbin.

Clint Williamson is a PhD Candidate in English at the University of Pennsylvania.

This post may contain affiliate links.