“Old Brooklyn Bridge,” by Joseph Stella, 1941

This essay first appeared in the Full Stop Quarterly, Issue #9. To help us continue to pay our writers, please consider subscribing.

I. TWO MANIFEST DESTINIES

In 2004, painter Alexis Rockman debuted a masterly 8-by-24-foot mural that depicts the Brooklyn waterfront on a summer sunrise in 5004 CE, thousands of years after the Anthropocene climate catastrophe has flooded over the continents and rendered homo sapiens extinct. The waterfront (and presumably all New York City with it) is totally submerged in water, while the East River and surrounding harbors are blended with the Atlantic Ocean. It is a complicated scene to judge: Although a ready new oceanic ecosystem comprised of water birds and tropical fishes shows signs of repopulating the area, harmful remnants of the human past yet persist. In the right half of the mural, a barrel of undecomposed industrial waste leaks oleaginous toxins into the rust-colored water, and toward the middle, an oil tanker strews the ocean floor next to a nuclear submarine. Still, the stubborn resolve of so many different plant and animal species, including a few large sea mammals, suggests that some measure of flourishing is still possible in the semi-toxic sludge of Brooklyn’s ruin.

Rockman’s mural, titled Manifest Destiny after the nineteenth-century American myth, pictures the fatal consequences of modern capitalism’s pursuit of unending economic growth, showing how manifest destiny’s fulfillment—the spreading of consumption-driven capitalist economies worldwide—paradoxically entails humanity’s demise. Yet by picturing life’s struggle to reclaim the post-human Earth, the mural also turns the old myth on its head, revealing an alternative manifest destiny of nature that predates and outlasts humanity’s existence. This other manifest destiny concerns only what the system of nature as a whole has always done,what it will continue to do after humanity, and that is to exist inexorably according to its own laws. In this biocentric (as opposed to anthropocentric) retelling, nature is the ultimate arbiter of its own fate, indifferent to the fate of human beings or any other species that temporarily holds the spotlight on Earth’s eternal stage.

Rockman’s biocentrism seeks the inverse of what Alexis de Tocqueville, in Democracy in America, observed to be one of the main tendencies of nineteenth-century American thought: the elevation of humanity above all other muses, including nature or God. Tocqueville attributed this tendency to democracy’s recent revolutionary uplifting of ordinary people to the status of social equals with a determining role in their society’s fate. This revolution in politics was contemporaneous with a revolution of mind that turned democratic man’s attention chiefly upon his own raised standing in the world. Newly cognizant of his capacity and his right to shape society as his will dictated, he began to deny that nature held any metaphysical power over him. This shift of consciousness inevitably infiltrated his intellectual culture, Tocqueville noting the impact democracy had already made on American poetry and the arts in particular. “The destinies of mankind, man himself taken aloof from his country and his age,” he writes, “will become the chief, if not the sole, theme of poetry among [democratic] nations.”

Supposing there is something true in Tocqueville’s observation, it is easy to see how a myth like manifest destiny could grow organically out of nineteenth-century political thought. Rockman certainly sees the connection between American democracy, then rooted chiefly in Anglo-American identity, and the destinarian outlook that led to environmental catastrophe and the expropriation of Native lands. Whether he thereby scorns democratic man’s hubris or celebrates nature’s perseverance (or both) remains a matter for interpretation. Yet by representing nature as the arbiter of a fate larger than politics, he shows, at least, how restricted the domain of human agency is, how it is a mere function of the system to which it belongs, without any contra-causal power over it. Manifest Destiny reminds those who would seek, for humanity’s sake, to reverse or mitigate our ongoing climate catastrophe, that nothing less than a total restitution of our limited agency with nature’s inviolable laws must be achieved. At a bare minimum, our current anthropocentric civilization must be revolutionized into a biocentric one—i.e., one that makes life as a global system its central focus.

A question arises, however, whether such an outlook would be heedful of or indifferent to the manner in which the restitution of humanity and nature is pursued. Must a biocentric outlook be committed to the democratic ideal of justice underwriting the misbegotten myth of manifest destiny, or must it, in consideration of the political and ecological wreckage of the last three centuries, throw the democratic baby out with the radioactive bathwater?

II. DEMOCRATIC NATURALISM

In 1836, a year after Alexis de Tocqueville published Democracy in America, Ralph Waldo Emerson came onto the literary scene with his first major essay, “Nature”. In it, Emerson summarizes the democratic naturalism of which he is the nineteenth century’s leading voice: “Nature is made to conspire with spirit to emancipate us.” The rest of the essay is an exposition of this statement, resting on the premise that nature is an analogue through which human consciousness comes to know itself. Nature’s conspiracy with spirit happens when man compares his own inner world to the outer. When he perceives a correspondence between the plant’s growth and the growth of his philosophy, or when he sees the movement of his thought reflected in the steady flowing of a river, he becomes an active participant in the conspiracy, learning how he fits into the cosmos’ overall scheme. Every insight gained from nature is thus about himself: the more he studies it, the better he knows how to design and direct his own activity, and the more self-determining he becomes.

Emerson connects the themes of “Nature” to democracy in his 1837 lecture, “The American Scholar”, where he compares the intellectual uplifting of the “suburbs and extremities of nature” to the political enfranchisement of “the lowest class in the state.” For Emerson, the ongoing revolution in politics that produces democratic man links the ploughman’s productions and nature’s creations to the common principle of infinite freedom. In a reversal of Hamlet’s charge, man does not project his own consciousness onto nature, but rather sees in the mirror of nature the shape of his own free thought and action. As his primary educator throughout life, nature cannot but seem to man to be instrumental to his own projects. (When the ploughman ploughs his field, he works upon a pliable object that satisfies his basic needs and alters according to his will.) Yet if the law of the human mind is the freedom of practical reason, as Emerson consistently maintains, then it is also the case that the ploughman cannot dominate or exploit nature, from which he learns of this law, without doing a harm to himself. Nature and spirit must conspire if humankind is to be emancipated. “In fine,” says Emerson, “the ancient precept, ‘Know thyself,’ and the modern precept, ‘Study nature,’ become at last the one maxim.” Democratic man cannot know himself–cannot be emancipated in his reason–without having understood how that same freedom obtains in the outer world and having reconciled his own willing with it.

Emerson developed his democratic naturalism in the same intellectual climate that produced the myth of manifest destiny. Jacksonian populism reigned in the national government and an industrial revolution, powered by the surplus capital filched from slave labor, was exploding continent-wide. Yet as Leo Marx explains in The Machine and the Garden, Emerson proved to be anything but an anti-industrialist. In fact, he sought to reconcile the stringent material requirements of the new democratic freedom with his own pastoralist regard for nature. His essays embrace the future heralded by industrial machinery, believing it will make material life less arduous for working people, thus freeing up their time for the natural education outlined in “The American Scholar”. In a brilliant summary of Emerson’s view, Marx writes that “The industrial revolution is a railway journey into nature.” But if man requires technological artifice to prolong his natural education, then this means that his emancipation is actually a two-part process: First, he receives from nature, his primary educator, the law of the world, which he discovers to be the law of his own consciousness mirrored. Second, since that law concerns the infinite freedom of nature and reason, he strives continually to refine his perceptions of it, developing whatever techniques may be useful to that end, so as to gain ever more insight–and ever more self-determining power–from his study.

Emerson’s successor in poetry, Walt Whitman, works out a similar program in Leaves of Grass, although he sheds his predecessor’s romantic pastoralism in favor of an iron naturalism more befitting of the industrial era. In “Song of the Broad Axe,” for example, after surveying the continent’s pine and oak forests, copper and coal mines, and so on, Whitman affirms the forward march of industry and commerce in these places: “The axe leaps!/The shapes arise!/Shapes of factories, arsenals, foundries, markets,/Shapes of the two-threaded tracks of railroads,/Shapes of the sleepers of bridges, vast frameworks, girders, arches . . .” What these manifold shapes amount to, for Whitman, is the overall shape of “Democracy total,” the inevitable result of centuries of mass movement out of feudalism. The “turbulent manly cities” of the mid-Atlantic coast are the as yet incomplete concretions of that totalizing ideal. In Democratic Vistas, Whitman remarks upon the “splendor, picturesqueness, and oceanic amplitude and rush of these great cities,” analogizing their complicated webs of relations to a teeming ecosystem. The city is the natural world remade by the human hand, proof of the strong analogy between democracy’s and nature’s processes. Indeed, the goal of democracy is to win by experiment laws that will govern humanity as if they were natural ordinances—laws which, once established, will be capable of carrying on by themselves, without tyrannical enforcements.

Whitman calls upon a class of national poets, similar to Emerson’s class of American scholars, to rise up and become lawgivers for the human soul, taking what they have learned from nature—“the only complete, actual poem”—and transfiguring it into a single synoptic legislation for everyone. Their poetic legislation sublimates the common law, affirming what is natural and free and just, pointing out what is still missing, and rejecting anything that excludes any human being from partaking of the common weal. As Whitman conceived it in 1871, the task of these poets was to record an ongoing spiritual resistance to the vulgar materialism then overtaking the national life. As industry and capitalist commerce flouted natural law and exploited the laboring masses, Whitman charged his poets to imagine a world in which the emancipation of democratic man and society’s harmonization with nature would be one and the same task.

This democratic naturalism was as much a part of nineteenth-century manifest destiny as was global political and economic dominion. Such a philosophy contained all the contradictions of its historical moment. An egalitarian worldview that dignified human thought and action to new moral heights coevolved with a profit-driven social system that exploited nature and human beings with unprecedented efficiency. In the 150 years since, nature and history alike have begun to pass their judgments on these contradictions. Today, the oceans swell with melted ice and encroach upon the world’s coasts in response to the globalization of commodity consumption, and the coexistence of democratic universalism and systemic inequality has, for an ever-increasing multitude, become humanly intolerable. As the habitable earth heats and shrinks, this multitude learns that the only path toward a restitution of nature and human existence is to abolish the worldwide political-economic domination that offends human freedom, and to deliver a new legislation that upholds a democratic ideal of justice for all.

III. BROOKLYN BRIDGE

One of the notable presences in Rockman’s Manifest Destiny is the Brooklyn Bridge. Once the crown jewel of New York, the bridge, in 5004 CE, has become a roost for seagulls. Its middle causeway is collapsed, its suspension cables, snapped. Its twin towers, half-sunk in the ocean, are foliated over with kudzu. The towers in particular invite comparison with the “two vast and trunkless legs of stone” left standing at Ozymandias’ desert effigy. And the waters moving under them, like the sands of Percy Shelley’s poem, stretch “lone and level” into oblivion, swallowing all remaining signs of civilization. But whereas Shelley’s poem reports on Ozymandias’ ruin through the mouth of a traveler who has seen it for himself, Rockman’s painting imagines the Bridge without human eyewitnesses, severing it from the chain of memory that would conserve it within eternity’s immemorial flux. Abandoned to that flux, the bridge imparts no clue to the seagull that it is any different from any other rock jutting out of the sea.

The Bridge’s desecration indicates how Manifest Destiny judges the value of one of the nineteenth century’s greatest technological achievements. For Rockman, the bridge is just one more hunk of unformed rock, its status as a singular wonder of its era long forgotten. The modern contradictions that built it, moreover, have proven unsustainable: capital and labor, industry and nature, embattled even as they conspired to build a world, in the end could not dwell in the world they built.

Hart Crane’s The Bridge imagines an alternative to Rockman’s apocalyptic vision. The poet builds on Emerson’s thought that democratic emancipation and natural law are reconcilable. In contrast with Rockman’s wasted slab of rock, Crane’s Bridge, portrayed at the height of its twentieth-century grandeur, is positively ebullient. Crane describes it as an “intrinsic Myth” (in the sense of symbol) for an America in dire want of spiritual uplift. Crane hoped that his poem would not only raise it up as a symbol of America’s democratic toiling, but also show its point of fit within nature. In this regard, his work is an adaptation of Emerson’s democratic naturalism to the twentieth century, and his Bridge is a symbolic link between the law of human consciousness and natural law.

Two standalone odes to the Brooklyn Bridge, like the two towers of structure itself, bookend a sequence of historical poems that moves mercurially through time and space. It is clear from the beginning that Crane chooses the bridge as his mythic symbol of America because it is the most conspicuous public work in the country’s most conspicuous city. It belongs to a larger network of bridges, roads, and transit systems that pumps the life-blood of New York City and integrates its millions. Brooklyn Bridge thus forms part of the constitution of society in the classical sense of the word, being one of a totality of points of contact between the people and their political state. As such, it lets the people experience the state as the precondition of their livelihoods and product of their labors. The same principle extends to the rest of the country’s infrastructure: From Atlantic to Pacific, macadam and iron underwrite the possibility of concerted activity on a continental scale, lending form and order to the democratic manifold in a way that individual cognition simply cannot. Infrastructure thinks what cannot humanly be thought. “O Thou steeled Cognizance,” Crane calls Brooklyn Bridge in one poem, “whose leap commits/The agile precincts of the lark’s return; Within whose lariat sweep encinctured sing/In single chrysalis the many twain.”

Still, Crane’s decisive reason for fixating on Brooklyn Bridge is that it transcends its functionality as a public work. The bridge is, besides a lifeline over the East River, a wonder of human engineering and art, destined from the beginning to become a hub for all kinds of urbanites, from vendors and artists to sex workers and even suicides: “Out of some subway scuttle, cell or loft/A bedlamite speeds to thy parapets,/Tilting there momentarily, shrill shirt ballooning,/A jest falls from the speechless caravan.” The bedlamite’s radical choice falls within the wide spectrum of freedoms made possible by the Bridge’s existence. Prophets pray at its altars, conmen scheme in its vaults, and a thousand idle Bartlebys, perched in high-rise offices, gaze abstractedly on its towers. Stuffed with the city’s human traffic, the Brooklyn Bridge is above all a symbol of free movement within the shiftless multitude. Crane’s alternately compressed and meteoric lyrics transcribe this free movement into a baroquely structured music: “And Thee, across the harbor, silver-paced/As though the sun took step of thee, yet left/Some motion ever unspent in thy stride,–/Implicitly thy freedom staying thee!”

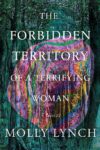

Crane hears music in the Bridge’s very design. To him, it is a harp of “choiring strings,” its suspension cables strumming “one song devoutly binding.” The musicality of Crane’s Brooklyn Bridge recalls Joseph Stella’s polyptych Voices of New York Interpreted (The Bridge’s cognate in futurist painting). There, Stella makes the curving cables and crisscrossing wires–the strings of the poet’s harp–the focus of his study, twining symmetrical strands of illumined wire through two pointed archways that open to grim silhouettes of Manhattan skyscrapers. Juxtaposed curving and rectilinear figures cause the bridge’s entire form to veer vertically, toward a night sky that resembles one of Edgar Allan Poe’s roiling maelstroms. Stella’s (and Crane’s) intended sonic effect is that of beating drums and buzzing wires, sounds that carry force enough to command the city’s full attention.

Unlike Stella, however, Crane is never so in thrall to the bridge’s pure form that he forgets its material rootedness in nature. Whereas Stella paints a riverless bridge, Crane’s has a river running under it. This is no trivial contrast, since the two great rivers referenced in The Bridge–the East and the Mississippi–consistently flow in a temporality that is distinct from the runaway technological time of the city. The East River is “sleepless” and eternal; the Mississippi follows the “alluvial march of days.” In New York City, by contrast, time is an ephemeral number, “the same hour though a later day.” In a tribute poem to Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle, Crane describes an untimely Manhattan sleeper slowly becoming aware “that he, Van Winkle, was not here/nor there. He woke and swore he’d seen Broadway/a Catskill daisy chain in May.” Facing an urban timescape that outpaces the poet’s power to cognize it, Crane deftly weaves river-time back into city-time in order to show how nature yet persists in the mania. Consider “The Tunnel,” for example, where the poet describes the hands of the Brooklyn Clock Tower maniacally counting time by day, then sinking by night into the fluid black of the East River: “Tossed from the coil of ticking towers . . ./Here by the River that is East–/Here at the waters’ edge the hands drop memory;/Shadowless in that abyss they unaccounting lie.” The bridge is a mediator of these clashing temporalities, “translat[ing] time into a multitudinous Verb.”

The Brooklyn Bridge, for Crane, is not ultimately a symbol of human consciousness’s transcendence from nature, then, but of its profound integration with nature. It is an ingenious human appendage to nature’s already existing public works, i.e., rivers. Crane even addresses the Bridge as “O River-throated” in his closing ode, confirming that the bridge’s song is just the river’s own re-voiced. Understanding this clarifies how he is thinking about the relationship of nature and industry throughout the poems, even when he is not talking specifically about the Brooklyn Bridge and the East River. Nature underwrites the industrial form of life everywhere, and this is nowhere more evident than in places like the Dakotas, far from any coastal city, where mountain streams murmur under humming telegraph wires, and the locals count “[t]he river’s minute by the far brook’s year.” In such passages, Crane translates the outmoded naturalism of Emerson and Whitman into his own twentieth-century context, proving that history has not rendered their democratic ideal irrelevant.

The Bridge is a re-gifting of the democratic naturalism the poet received from the nineteenth century, presenting an elegant counterpoint to manifest destiny. Yet what makes Crane’s modernist epic so instructive for the twenty-first century is how it discovers ample room in nature for humanity’s freedom struggle. Had Crane been alive to view Rockman’s Manifest Destiny, he might have advised that remaking our world from a human-centered into a life-centered one does not require us to abandon our most sacred humanist ideals. It requires us, rather, to find their fit within nature’s own manifest destiny, and embrace that determining law as our own. Nature has ever been democracy’s proper home. Crane’s Brooklyn Bridge lends nature a myth on behalf of humanity’s “lowliest”, its incompletely emancipated, from whom all valid myth ultimately issues:

Sleepless as the river under thee,

Vaulting the sea, the prairies’ dreaming sod;

Unto us lowliest sometime sweep, descend

And of the curveship, lend a myth to God.

Kelly Swope lives in Nashville, Tennessee, where he works as a graduate student and teacher. He is currently writing a doctoral dissertation on G. W. F. Hegel’s philosophy of education. He hails from Granville, Ohio.

This post may contain affiliate links.