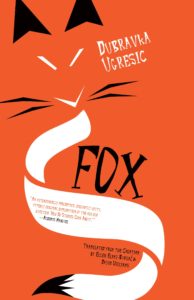

Tr. from the Croatian by Ellen Elias-Bursac and David Williams

The fox is the totem of cunning and betrayal; if the spirit of the fox enters a person, then that person’s tribe is accursed,” writes Pilnyak,

writes Dubravka Ugrešić in Fox, writing about Boris Plinyak, who writes about the Japanese writer Tagaki in “A Story abut How Stories Come to be Written.”

Pilnyak as been has been advised to regard the fox as “a totem of cunning and betrayal,” by Comrade Dzhurba, who “takes Pilnyak into the mountains above the city to show him a temple to the fox.” There is an altar in this Japanese temple on which foxes take their rest. It’s there, Ugrešić tells us, that Pilnyak asks how stories come to be written and it’s there, on page two of Part One of her literary excursions that Dubravka Ugrešić lays out a bait:

All told, it seems that Pilnyak was right; there is much that qualifies the fox as totem of the traitorous literary guild.

I try to understand Ugrešić’s point: As the narrator of Fox relays to the reader how the writer Boris Pilnyak wrote “A Story about How Stories Come to Be Written” — telling the story of the possibly invented Japanese writer Tagaki, who wrote a very well received novel about his Russian wife Sophia Vasilyevna Gnedikh-Tagaki, inspired by “spying” on all aspects of their erotic and emotional relationship, whereupon she, after discovering herself to be the main character of that fiction, separated from Tagaki and wrote her own autobiography — will the reader go into the trap and conclude that writers must be traitors committing betrayal in the first, second, third or fourth degree, or loyalists attempting repatriation of that betrayal, or a hybrid of both? Why the word “traitor?” Are writers for Dubravka Ugrešić part of the “the traitorous literary guild,” because for them everything that happens is nothing but “material for observation,” and is the act of “committing pen to paper” first of all an activity that betrays the principal of living by choking life into life sentences?

What if it’s true? What if writing is betraying? Is reading then being betrayed? I wonder. As I try to picture the foxes in the temple taking a rest on the altar a memory slips in. When I was about ten I told my father that I had never seen a fox in real life and that I needed to see one. I had been urged by adults to read fox stories. A collection of fables and fairy tales had been put on my table and the doings of the fox in them conflicted each other, which confused me. Why was I supposed to read these stories? Who was the fox supposed to be? A smart trickster, a mean loner, a slick, inventive liar, a killer of chickens, a funny guy, a relentless survivor?

In his introduction to a translation of the medieval text Reynard the Fox from Dutch into English, James Simpson suggests that the story of Reynard’s moral wrong-doings is the base for Niccolo Machiavelli’s scandalous book The Prince, written in 1513 as an advice book to rulers. In The Prince Machiavelli argues that “virtue is insufficient,” and that the preservation of power depends on force and trickery. “However,” James Simpson says, “whereas Machiavelli had counseled kings to survive their enemies and subjects, Reynard, is rather about how clever subjects can survive enemies and kings.” Could virtue simply be seen as virtuosity? Could the fox be admired for performing a considerable virtuosity in lying?

Growing up talking about books at home was a taboo. There was no way one could say it any better than the writer had expressed it. Any attempt to discuss what was going on in a written story with one’s own words was poorly mimicking the writer and degrading literature badly. Still I needed to know what was going on with foxes. I needed to see a real one. Having very little time, my father drove me to a guy’s compound instead of into a forest. The moment I looked at the frightened animal in the corner of a dirty cage, I knew that writers and storytellers were dangerous manipulators. They had made me believe that a fox was as big as a pony, even though none of them had explicitly said it. I felt embarrassed for the fox being so small, shy, and helpless. The guy laughed a stupid laugh. I marched out of the compound angrily. I knew the fox hadn’t deserved me looking down on him like that and concluded that I needed to avoid reading stories in which animals were being used as characters with human traits. For a while, I thought of books as cages and the idea of reading as being captured — in silence.

Dubravka Ugrešić’s use of the metaphoric fox in Fox made me think of the fox in Herta Müller’s deeply stirring book The Fox Was Ever the Hunter. There the fox mainly appears as a fur that lies flat on the floor in an apartment of a teacher, who is under active surveillance by the Ceauşescu’s regime in Romania. When the woman comes home from her senselessly rotting working days in this corrupt, foul smelling dictatorship, she finds the foot cut off her fox-fur and neatly placed next to the fur. There is a cigarette butt in the toilet bowl. Another day the tail is cut off. Another cigarette butt swims in the toilet bowl. Then the head is cut off, then another limb. For a moment I gave credit to the members of the Rumanian Secret Service for engaging in such strange and absurd ways of intimidation, yet as the story progressed I realized, it was not strange, it was not absurd, but utter, senseless cruelty. Every day, they cut off another piece of common sense and neatly placed it next to the meaningless. There was no other reliable logic but the violated fox-fur lying flat on the floor having to endure being cut up systematically while the meaning of life swam in the toilet bowl, and survival came as a bottle of schnapps on the kitchen table.

Herta Müller grew up in Romania and emigrated to Germany in 1987. Dubravka Ugrešić grew up in Yuguslavia and emigrated to the Netherlands in 1993. They are only four years apart in age. They both left for political reasons and wrote about the catastrophic pasts of their countries in very different ways. What connects them, I think, is their reluctance to fully trust in words, in the structure of language and stories. Not in theirs, not in ours, not in anyone’s.

“You think the beauty of your voice suffices, everybody will hear it, and its your job to sing. Yet you, yourself, know things don’t work that way,” says the widow of the writer Levin to the narrator of one of Ugrešić’s stories.

Throughout reading Fox I felt I was lured into something slightly destructive I could not resist admiring from the outside. Something about Ugrešić’s literary investigations challenged me in clever, daring, and persuasive ways to become complicit in participating in something that didn’t really suit me. I have struggled since then to put my finger on what exactly causes my persistent fascination and uneasiness with this book. Is it a matter of missing intelligence on my part? A missing gene for meta-fiction? Is it a matter of tone or translation, or where one sets one’s baseline, the fear of missing out? Why continue reading?

What’s admirable about the fox in many European folk tales is that he has thoroughly studied the shortcomings and behavioral patterns of his victims. Just as the fox can count on the bear’s greediness to put his head into the beehive for more honey, the writer can count on the endless greediness of her readers wanting to read more.

“Who are you then?” Faust asks Mephistopheles in the first part of Goethe’s Faust.

“I am part of that power which eternally wills evil and eternally works good,” says the devil to the scholar.

There is an evasiveness that comes and goes with Fox, a reality that travels with familiar looking luggage but never finds a home to set it down. What feels familiar about the luggage is its sturdiness and that it contains a certain fear. Maybe it’s the fear of the suitcase to become obsolete once the luggage is unpacked and stored away in a cozy bedroom chest.

To evade means to escape from something by trickery or cleverness, to avoid answering directly. Ugrešić consistently evades, sometimes relentlessly, sometimes passionately, sometimes slowly in a very calculated manner and sometimes sloppily, in a manner that is at times careless, funny, sad, stupid, derogatory, scornful, smart, honest . . . it’s not really predictable what will come next. She has mastered the skill of playing with open words a deck of cards that doesn’t match, that is not one deck, but many different ones. Her force is slick and confident and can at times be arrogant and harsh, as when someone steps on her tail, which only she is allowed to suck if she occasionally needs to curl up and come full circle.

In an interview, part of the “Current Conversations” series funded by the University of Oklahoma and World Literature Today, R.C Davis-Undiano asks Ugrešić about leaving Yuguslavia in 1993. She says:

So my position was impossible, I could not breath anymore, and I simply left. And besides, before that, I also managed to become a public enemy, so I was accused by media, by local media, because of what I had written, that I am a traitor, that I am a public enemy, because I did not support that prevailing policy of nationalism.

It’s not the word “traitor” but the word “nationalism” that immediately triggers Davis-Undiano to call Ugrešić a “Citizen of Literature,” and while reading Part Two, Three, Four, Five and Six of Fox I often thought back to that magic moment when he said, “Citizen of Literature.”

Reading Fox, I repeatedly wished for Ugrešić to have stayed “home” in that old, majestic, dark and quirky house where I imagined the “Citizens of Literature” would work and live and stir around in references, pseudonyms, footnotes, quotes, maps and dust, and stacks of grand and detailed literary knowledge. I wanted her to stay indoors, inside as an insider. I’d rather endure a sort of intense literary cabin fever, I thought, than having to follow her out into the open alienation where she schleps her books and quotes and knowledge and occasionally gets exhausted, scornful, and bitter from having to deal with trivialities, living writers, bed sheets, and tourists.

I wanted the “Citizen of Literature” to keep brewing and cooking in invented versions of historical territories of Germany, England, China, Japan, the United States, Greece, Turkey, Palestine, and Mongolia, Leningrad, Moscow, Peredelkino, Belgrade, and populating those places with characters like Olga Scherbinovskaia, Kira Andronikashvili, Boris, Nabakov, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Nikolai Khardzhiev, Nadezhda Mandelstam, Maxim Gorky, “madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels and skeptics,” instead of complaining about having to sit in economy class in airplanes, taking medication for back pain, having to fly to academic conferences where they don’t pay the writers well, staying in cheap hotel rooms, and attending tourist tours of tourist sites in tourist destinations, so she can be “overcome by a sudden attack of misanthropy.” But then I thought: Can I not grant a writer the right to be human? Can I not admit that the “Citizen of Literature Home” is either a prison or a homeless shelter and not a place where real life people laugh and smile and touch and love? Can I not have a bit more empathy that the literary scholar needs to pay her bills and that her aging body hurts at times? Do I as a reader always sit upright like a Citizen of Literature in a mid-century armchair in front of a window with a cup of steaming tea on the side table, or do I not sometimes drag my books to the toilet, where I read the most precious passages of world literature hunched over while my exposed ass hangs above a white ceramic bowl filled with urine?

Responding to a question about language and nationality in an interview with Michal Špína and Strahnija Bućan Ugrešić says,

In all my books I try to make references to Central and East European literatures, because they do not get the recognition they really deserve. In my novel Baba Yaga Laid an Egg, and in my new novel Fox, which is about to appear soon, I intentionally make use of references to the languages, literatures and places of Central and East Europe. I am delighted when my book is translated into some ‘big’ language, like English, for instance, because, among other things, I feel like I am smuggling neglected Central and East European literary values into World literature.

What is this World literature that smuggles values from place to place? Ugrešić turns to Walter Benjamin’s statement that:

World literature is like a whale around which suckerfish gather like practiced pirates. They attach themselves to the whale’s body and vacuum the parasites from its skin. The whale is a source of food, protection, and means of transport. Without the suckerfish, parasites would settle on the whale’s body and the body falls apart . . . I have no illusion about my literary talent. I am a literary suckerfish. My mission is to attend to the whale’s health.

Where is the fox in this equation? I am trying to imagine. The big whale is in the big ocean. He swims in his métier, in his language, in his culture. He is very lucky in that way. One day, things change. They drain the ocean, they burn the books, they persecute the writers. That’s when the foxes come in. They are the smugglers. They take those suckerfish and bring them to another ocean where they slowly learn to suck off the parasites of another big whale. Without the fox, much would be lost.

I am not sure if I would call Fox a novel, and I can’t say that I liked it — which is what I like most about it, that it’s simply not that likeable, and not that likely, and not that predictable. It constantly interrupts its own flow and questions it’s own trustworthiness and I appreciate that as a quality and as a strategy to keep people on their toes, aware and flexible to imagine and occasionally embrace the other side. It’s a bit of work to read this book, and that is annoying at times, but when you get to the end, where you enter the compound and step up to the cage — there is no fox inside. The cage is empty. What a relief.

Franziska Lamprecht is an artist who started writing as an extension of the long-term process based works, she produces together with her husband Hajoe Moderegger under the name eteam. Their projects have been featured at PS1 NY, MUMOK Vienna, Centre Pompidou Paris, Transmediale Berlin, Taiwan International Documentary Festival, New York Video Festival, International Film Festival Rotterdam, the 11th Biennale of Moving Images in Geneva, among many others.

This post may contain affiliate links.