Like a rising pressure gauge as a diver travels deeper to the lowest points of the ocean, reflection threatens me with an explosion of emotion. My parents did not tolerate tantrums, so I became an expert suppressor—that is, until I could pile enough pillows and blankets on my head and scream.

As I laid flat on my back in the bed I briefly shared with my ex-boyfriend, my mind returned to a conversation one month before we stopped speaking. He was sick again —it happened at least once a season since he moved— and his coworker began to notice a pattern. He told me she said, “Did your Trinidadian ex cut a lock of your hair?!”—a cheeky invocation of a stereotype of Caribbean’s practice of Vodun, Santeria, and Obeah. It is rare that people read me as a Caribbean-American. I can’t conjure an accent; my physique doesn’t inspire offensive exoticizing inquiries about what I’m mixed with; and I certainly don’t move the way a Caribbean girl “should”.

Perhaps the most Caribbean thing about me is my taste for the gothic. In it, I find refuge for my yearning for love from country, from family, and yes—from men. When I think about it, sometimes I chuckle; other days, like today, I suck my teeth and swipe at the air.

As I write, I’m listening to “Needle and a Knife” by Tennis, as I have at least once a day for about a month. “Only a lonely love can devour you / but when you’re lonely the same love/ empowers you, yeah.” Crystalline wetness has pooled on either side of my nose, but it’s an empty threat: I refuse to cry this time.

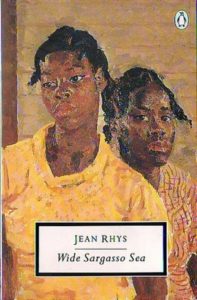

I may not have read Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea if a friend had not gifted it. My copy features a post-impressionist portrait on the cover, Two Jamaican Girls (1937) by Augustus John. One stares pensively off the page, the other directly engages me with a piercing gaze.

The three of us have mastered the vacant looks that barely contain wild passions and gnawing sadness—and Antoinette Cosway, the heroine, if you will, makes four. I didn’t expect to relate to a half-Martinician Creole daughter of an enslaver and plantation owner, but maybe—whether cultured or not—some of us carry a melancholy we just recognize in one another. The ragged Caribbean woman whose culture-bound madness drives her to set ablaze Thornfield Tower and fling herself from it’s heights in Jane Eyre finally gets an intervention that explains the series of rejections that consumed her mind and, ultimately, body.

The Caribbean has such an interesting geography; it’s neither South America, nor its own continent. On another timeline, it might have just been an assemblage of landmasses in the Sea. In this one, the theft of land and human beings, which left behind fractured histories and restless spirits, and life in the unpredictable beauty of the sea creates a proud, exclusive fraternity. Seemingly impenetrable, even if the fire in your blood marks you as one of them. Antoinette would never be English—Charlotte Brontë alludes to darkness in more than just her hysteria—and she would never be Caribbean—as she fell from the tower she reached for Tia, maybe in hopes of covering the chasm between a chosen exile and forced displacement.

As Annette’s distance from her daughter turns to disdain, Antoinette’s quest for someone to receive and reciprocate her love drives her. She reflects, “So between you both I often wonder who I am and where is my country and where I belong and why I was ever born at all.” These questions linger over my head like a fukú. It’s a perfect recipe for a lifetime of identity crises. I’ve only seen one grandmother’s country because I was born in it, but I’ve never even been to the state she was born in. I’m enamored with a birthright that feels just out of reach. Longing is like the consumption. With a name like that it should be a sickness of gluttony, but it’s the kind that consumes you.

He was my first love, but more accurately he was the first to feed my hungering infatuation with mutual interest and attention. Previously, my poor stomach was forced to devour its own bile and tissue to survive following years of lovers leaving my empty mouth gaping. When Ganja Meda, in Bill Gunn’s rebellious Black vampire film Ganja & Hess, finds her husband’s frozen and blood drained body in Hess Green’s freezer she is shocked – perhaps saddened, but she’s previously depicted as a spoiled, narcissistic woman with a saccharine cruelty about her – though she ultimately doesn’t turn away from Hess. In fact, the gruesome discovery draws them closer: they marry and Ganja herself is drawn into the life of compulsive consumption. For Hess, her presence is a reprieve from the loneliness of his curse. But he’s projecting; what he needed was a cure.

I’m anxious with fear I’ll only know my family as well as one can through secondhand stories, so I have filled the spaces between each country that bore a generation of my family with fantasies. I imagine the graveled road to my father’s childhood home a little disheveled, but flanked by wild tropical plants with names that sound most beautiful in the singsong lilt of Trini English. But what do I know?

I move to the living room and sit on the floor in front of my bookshelf. I thumb the spine of one of my favorite collections of essays, When You Are Engulfed in Flames by David Sedaris. Fire brings the promise of very serious transformation and I finally understood why jumping was not enough; Antoinette had to burn it, too. The root word of Caribbean translates to cannibal so it must simply be in our nature. I opened my chest up and exposed my insides to the elements only to find that I left my stomach empty for too long; there was nothing left. I have to find a better way to feed myself.

After weeks of waiting my passport has finally come in the mail. Nearly $200 reopened the possibility of visiting my grandmother’s, my grandfathers’ and my father’s countries to dig into family and find the pieces I have been looking for. Maybe I should just get a rental and drive to Alabama. Maybe then the longing will subside. Maybe.

In the last verse, Tennis’ vocalist, Alaina Moore sings “It’s the holiest fixation / and it’s taken cultivation.” Yeah.

Nailah Roberts is an Afro Caribbean-American writer. She writes poems and personal essays about living in a double diaspora. In addition to writing, she’s studying photography, collecting plants, and thrifting. You can find her on Twitter at @ndakhirah.

This post may contain affiliate links.