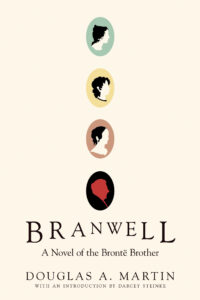

[Soft Skull Press; 2020 – Reprint]

In Darcey Steinke’s introduction to the fifteen year anniversary re-issue of Branwell, she remembers meeting Douglas A. Martin, when he was one of her students. “His stories about young gay men struggling for a place in this world, erotically and artistically, were shot through with a raw and supple longing.” It’s a theme that runs throughout Martin’s writing, giving poetic beauty to yearning and pain. Branwell is Martin’s second novel, first published by Soft Skull Press in 2005. His debut, Outline of My Lover (2000), has become a seminal work of queer auto-fiction. Writer, Hugh Ryan once referred to its genre splitting as, “fiction that drew on non fiction for its content and poetry for its form.” This is exactly right, Martin’s work reassembles reality with an imagined beauty. In the case of Outline of My Lover, Martin used his own experience as a young, working class, college student embarking on a round the world relationship with a famous musician as the basis for his exploration of complex relationships. In Branwell, the real life character is no longer himself, but the disgraced and dissolute Bronte brother of nineteenth century England. Whilst this might seem like a departure at first, especially as Branwell is not written as a first person, auto-fiction story, it still reads like a continuation of Martin’s earlier writing. He inhabits Branwell and reveals the story of his life with the same longing and poetic sensibility as he did in Outline of My Lover. His distinctive lyrical style is replicated in Branwell, skein-like sentences float over the page, rhythmically charting the pain and beauty of the world .

Martin’s story begins at the very start of Branwell’s life. As the Bronte’s only son, Branwell was born with an elevated status in the family and expected to become a great success, earning enough money to one day take care of his sisters. Martin tells us that, according to his father, “Branwell was to be the pride and joy of them all.” Unlike Charlotte, Emily and Anne, Branwell did not attend school or carry out chores, he was, by virtue of being a boy, given the freedom to roam and explore at will. Yet in those first years at their parsonage in Haworth, what Branwell discovered mostly was the pain of loss. By his ninth birthday, Branwell’s mother and two of his five sisters had died. It was an early childhood marked by tragedy. We learn that he and his remaining three sisters used toy soldiers to invent magical worlds and stories based on factual accounts of battles and began writing their own stories. Branwell believed, “to write, you took some things from real life and you made some up.” Something his sisters would, of course, go on to do with great success. Through Martin’s depiction of Branwell’s early life, the reader is reminded that whilst Branwell was a hero amongst his siblings, he is the only one history will fail to remember. Martin’s beautiful, stripped, melancholic prose points to the future failures that inevitably await Branwell. He is closest to Charlotte, they write together, but “he’ll never be able to gather together political, domestic, and amorous intrigue, not as finely as Charlotte anyway.”

Branwell cuts a striking figure with bright red hair fluffed to add height, and a raconteur’s ability to entertain the locals in the Black Bull pub. “Branwell leaves his shirt open at the neck, to show he is a poet.” In the pub, after a few drinks, he is a natural storyteller, a flamboyant entertainer. But after failing to achieve success as a poet, Branwell chooses to become an artist instead, still spending his evenings amongst the men, in the pub. He discovers liquid opium is cheaper than gin. “It will reveal things to him. It will reveal life. It will create a mist for him to walk in. It will keep him strong, protect him.” Martin’s use of the future perfect tense movingly takes the reader inside Branwell’s longing, his inner struggles. And it asks the question, what does Branwell need strength and protection from? When a new curate, William Weightman, arrives at the parsonage, he is mocked by the Bronte sisters for his femininity — Miss Weightman, they call him. Branwell notices the curate’s lips. But there is no direct talk of sexuality in Branwell. At the time, to be gay was a serious crime, and Martin retains the discretion required then, not allowing for language and ideas that were not known to Branwell, for they did not exist, at least openly. This adds to the ravaged, internalization of Branwell’s torment. What could not be said then, remains unsaid now.

The Bronte family spend their final years together at the parsonage when Branwell is dismissed from his post as tutor to a young boy, Edmund. In Martin’s novel, Branwell says it was because he had an affair with the boy’s much older mother, Mrs Robinson. Indeed, Branwell declares he and Mrs Robinson are madly in love and once her husband has passed, they will be united again. Historical accounts of Branwell’s life, most notably a biography by Elizabeth Gaskell, suggest this was true, but in Martin’s telling, the real reason for Branwell’s dismissal is the discovery of an inappropriate relationship with the boy, Edmund. Branwell invents the affair with Mrs Robinson so he can return home without shame. “In dreams, he was guilty of nothing. Only once he’s woken, facing his family. Things would have to be lied about.” This twist is at the heart of what Martin is trying to achieve with Branwell. By imagining an alternative corridor of history, Martin is able to reveal the depth of shame and subterfuge that will, at times, be inescapable for many gay people, not just those in Victorian England. Rather than merely hinting that Branwell might be gay because he was considered effeminate, or attracted to the company of men, Martin’s Branwell, whilst unable to announce it, forms a relationship, he is shown to be aware of who he is and the danger in doing so.

Like Jean Rhys, who, in her novel Wide Sargasso Sea, drew on her own experience and placed it inside a Bronte story, weaving feminist and postcolonial themes into a tale of Mrs Rochester’s early life, a prequel to Jane Eyre. So Martin is able to implant his own feelings within Branwell’s suffering, his wretchedness. Martin, who grew up gay in a working class family in the American South, interprets Branwell’s slide into mental and physical dissolution as the consequence of being gay when to be so was an impossibility. “There isn’t a word for it yet, that he knows, his feelings.” He is a man forced to live an invented, averted, and ultimately doomed life.

Reading Branwell, I was reminded of Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. It too, is the story of a young gay man, battling drugs, loss, abuse, and society; a work of queer fiction, which, like Branwell, is haunted by the experiences of the author’s own life. Yet Vuong, a fellow poet, is able to articulate the struggles of the protagonist openly, whereas Branwell cannot. Vuong has been given access to a language Branwell did not have, and Martin honors this. His Branwell is rooted in meticulous research and accurate detail but it is the imagined emotional depths of Branwell’s feeling that Martin seems to know best. In Branwell, Martin writes, “Bodies thought their own ways. Bodies wanted to follow themselves.” And this is the real tragedy of Branwell Bronte, not his shaming descent into madness, his addiction, or his failure to become a great artist. But, instead, he was prohibited from following his body. Despite Martin’s attempt to represent Branwell’s life, his marginalized existence, with the empathy and legitimacy that was tragically unavailable to Branwell in his lifetime, still it remains, the true life of Branwell Bronte is perhaps a story that will never be told.

Simon Lowe is a British writer and journalist. His stories have appeared in Breakwater Review, AMP, Storgy, Firewords, Ponder review, and elsewhere. He has written articles about books and society for the Guardian and BBC worldwide. His new novel, The World is at War, Again, will be published in 2021 (Elsewhen Press).

This post may contain affiliate links.