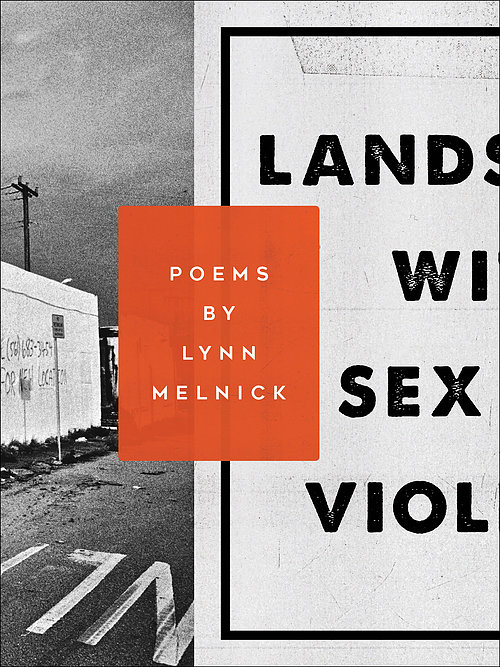

There’s nothing more to say about Lynn Melnick other than that she’s cool and fierce and witty and funny and angry and awesome. Her forthcoming collection, Landscape with Sex and Violence (YesYes Books), is – as we talk about below – relentless. Relentless in scope, relentless in image, relentless in tone and content. As it reckons with trauma and sex and violence, it does so in a way that offers up the poetic line as confession and resolution and survival. Yes, this book attests, page after page after page, I’m still here. The world doesn’t always seem to reflect the work that writers, women, and people like Lynn put into their lives and the lives of others, but I do not want to know what the world would look like without them. Lynn and I met in Queens to talk about the new book, this political moment, anger, the constant, ceaseless work of women, Twin Peaks, the act of writing, and so much more. It’s all below.

*Trigger Warning: this interview at times discusses the topic of sexual violence, and mentions the word rape.

DK: I was thinking about your book yesterday, when Trump tweeted about Morning Joe and Mika. It’s an interesting book to be reading now.

LM: It’s a weird book to be publishing now. I feel very strongly about that.

You have this one poem that I love, “Poem at the End of a News Cycle,” and in that, you write: “I’ve gotten to the point where I’m just going to tell everyone everything that’s ever been done to my face.” And I’m sort of wondering for you, when you realized this book was a book.

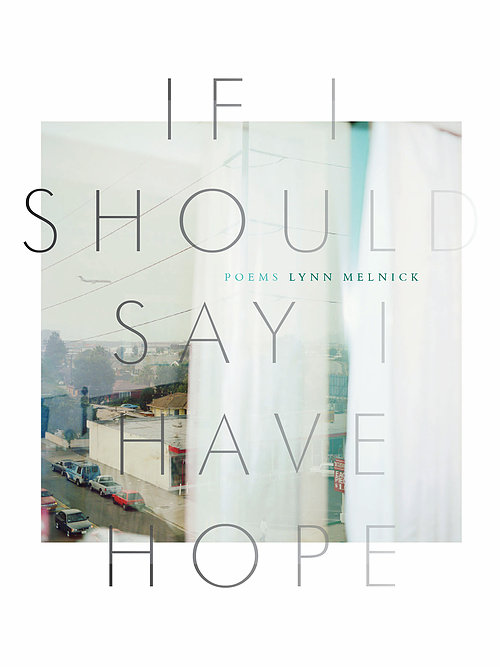

You know, that’s a good question. After my first book came out, which was like 5 years ago, I was so nervous. It took me a long time to publish it, because I just didn’t want people to read me. And I was just very shy about putting myself out there. Now I look at that first book, and it feels so tame and veiled and everything. It’s totally safe. And that book came out, and the sky didn’t fall in. I had several minor nervous breakdowns, but other than that – it all went well.

Sure.

So, I was like, I can now write the book I’ve wanted to write, since I’ve started thinking of my life in terms of rape culture and feminism. I said, you know what, my book just came out, I won’t have another book for a long time, so I’m just going to start writing these poems.

And this was how long ago?

This was 2012. And it didn’t really seem like a book to me. And then I happened upon this book – for one of my freelance jobs, I write press releases for major publishers. I happened upon this book called Trees in Paradise, about trees of California, and I started thinking about landscapes, and about how there are very few trees that are actually native to California, including the ones that we think of as the most Californian, like palm trees and eucalyptus – not native to California.

Wow. Didn’t know that.

Yeah! So it sort of takes you through the history of California by way of its trees. I got this idea that that’s how I’m going to do this. I’m going to talk about this dangerous, messed-up, haphazard landscape, but I’m also going to talk about myself and my body and my history. So that’s how I came to it. I don’t think I thought about publishing it.

Sure. How do you feel about it now? I guess in the wake of what you said about If I Should Say I Have Hope, and being nervous about that. And also considering that rape culture and sexual violence are becoming part of the national conversation.

It’s weird. It’s weird to be publishing it now. Like when the book was taken, I thought we’d have a female president. I was never one of these people who was like, oh, she’s a shoo-in, she’s going to win. I’m such a pessimist. I’m a secret optimist.

Hah, that’s a great term.

I practice pessimism so I’m never disappointed.

I feel like most poets are outward pessimists but have a tinge of secret optimism.

Yes! Like I really do want the best and think it’s possible, but I’m pretty sure everything is going to fail.

Right.

But anyways. When the book was taken, I thought there was a good chance that Hillary would be president, and that the conversation about rape culture would be, like, we’re going to do this thing, the world is going to be different for girls.

Yeah.

And then what happened, happened. And it just feels very, very different to be publishing it now. It feels like maybe we’re more aware of all of this, but –

Well, your book feels more like protest now.

It does.

It’s interesting being a reader, because when I read these poems, I’m doing that in the moment, and as I’m reading, I’m not considering that you’ve been writing these for the past few years.

That’s true.

Everything feels like it was written for the moment. Which is great in the sense that poems echo and have their own life. And if I was reading your book within the context of, say, a Clinton presidency, I think your poems would also take on a different life.

Yes, I think it is very different. I think you can’t have a more prime example of rape culture than Donald Trump.

I agree.

This is a man who has proudly admitted to sexual assault. Like, proudly. And then he’s our president. 62 million people voted for him. And the weird thing is that most of these poems were written about the 1980s and early 90s, but with a vantage point of now. A lot of it has to do with the fact that it’s an ongoing struggle. There’s a poem in there about street harassment, which is something that’s ongoing. But in terms of the darkest stuff, that was a long time ago, but it still feels weirdly relevant to me.

I was going to bring up the street harassment poem. It’s interesting – because you talked about your first book and this sort of shyness, but the voice in these new poems, tonally, can be like hey buddy or fuck you, it can be antagonistic and in-your-face. It’s awesome.

And in person I’m really shy and nervous.

Which is the beauty of writing, that contrast. I’m wondering what brings you to each poem, how you decide that sort of voice. Because there are some poems where you’re more reflective, some where you’re antagonistic. As a whole, though, it’s a very forceful collection.

Thank you. That’s a good question. It’s funny – I have two daughters. My youngest always describes me as sunshiny. And I’m like that’s so weird, that’s not how I see myself. Apparently I’m sunshiny, too.

Hah, that’s great.

I think, honestly, most of what guides my writing is anger. And I’m obviously not so secretly a very angry person. I’m angry about things that’ve happened to me. I’m angry about how the world treats women, including myself. I’m angry at the whole culture that allows for this violence to go on. I’m angry that women can’t be sexual beings, divorced from this reality of being objectified all the time. I’m just really angry. And a lot of times when I sit down to write, that’s what’s guiding me. I’m just really pissed off about something. And some of the poems in the book were written at my angriest moment.

Sure.

One of the ones you’re thinking of, “Some Ideas for Existing in Public,” which is about street harassment – I was just really angry.

The one that ends by saying “I’m yours.”

Yeah. I had been street harassed twice that week in front of my children.

Wow.

And that’s, like, really fucked up. I just don’t understand why a person would do that. And my daughter was like, “Why is that man yelling at you?” So I was just angry. And the other one I think you’re thinking of, with the word “buddy” in it, is “Landscape with Twelve Steps and Prop Flora.”

Yes. Which I love. You also have that line in there talking about – which, I should say, there are many points in the collection where I felt guilty as a poet – you have that line where you talk about the people smoking outside, and how their cigarettes are not like stars. And I’m like, goddamnit, I’ve done that before. And I’m going back through my own poems saying no, no, no.

Hah, that’s fine! Totally fine. I was just thinking in that poem – I don’t know if you’ve ever been to an AA meeting.

I have. That poem in particular is a dog-eared one. My mom is a recovering alcoholic. So I spent most of my childhood going to Alateen meetings, which is just something I can never stop writing about.

It’s a whole different world.

It really is.

I went to meetings for a while. I was a teenage drug addict. There’s something about the community of it, and also the weird cult-like atmosphere about it. And the fact that people in recovery can also be creeps, which always stood out to me, because I was so young. And that’s something I always write about, too.

I used to give little speeches to these, like, AA conventions, these big rooms of alcoholics. I was eleven. And it was strange. I would get this ornament at the end, and I’d be like, why am I getting this ornament? Anyways.

Hah, it is strange. But I’ve seen it save people’s lives.

Same.

And my whole thing is that, in that poem, I was sort of thinking about that culture in terms of rape culture, in terms of being a girl – I was like 14 – sort of on my own, left to deal with this very adult world. That’s where that came from. And it’s fine to call cigarettes stars!

Hah, thanks!

You know how when people exit a meeting and everyone’s a smoker? And everybody lights up. One of my very clear memories is of this guy who said, “Oh, it’s just like a thousand stars!”

Sometimes if it’s not one drug, it’s another.

Exactly. I started smoking in rehab, when I was 14. And this seems so wrong to me now, especially as a parent, but the attending counselors offered me cigarettes, like hey, try this instead. And I’ve only recently quit that.

Wow. But back to the anger thing – when you sit down to write an angry poem, what’s the next step? Do you edit? What’s the initial shape, say, of some of the more frustrated poems, and do you trim it down? I’m thinking of this because the anger comes out. It’s there.

Sure. Like how does it go from that feeling to a poem?

Yeah.

You know, it depends on the poem. I write pretty quickly. I don’t write that often. I’m always way up in my head too much, like I don’t notice my surroundings. Like if you hadn’t seen me earlier before this, I would’ve just been wandering around, even though as you pointed out, this place was literally right in front of my face. I just don’t notice things! I’m always thinking about stuff.

Haha.

And you know, everyone’s like write every day if you want to be a real writer, and I’m like fuck you. So by the time I get to the page, it’s been developing in my head somehow, and I sort of vomit it out onto the page, and then I shape it. The thing I probably revise the most is the look, the line length, and then I edit myself a little bit because I can get a little over the top. And then I tinker with it sort of endlessly, even though 90% of it is there on first write, I just tinker with it endlessly until its perfect. I’m pretty slow that way because of that, because I want it to be exactly how I want it, and I have this fear of being misunderstood.

Which is interesting, too. Some of these poems feel like fast poems. Not that they’re quickly written, but in regards to the speed at which you read them. I would find myself swept up in the momentum of certain ones.

And that’s how I write. And then with this idea of landscape and the flora of Los Angeles, I did a lot of other reading, and that was a little more plotted out. I would want to write about, say, abortion, but I didn’t simply want to say here’s what happened to me. I wanted it in context. And that’s what I was trying to do with this book, to put it all in context with the landscape that I was in at that time, and how that actually affected things, and how certain markers of that landscape still feel like those incidents to me. It’s not always rational. But I just want to write about how landscape triggers memory. And also – I hope it came through – I wanted to write about how language shapes memory, too, how the words for things shape memory.

That’s interesting – did the titles come first? Or when did you know, perhaps, that landscape was going to be a guiding theme? Was it not until you read that book about trees?

I’m trying to remember. That book came out in 2012. I think I may have written a couple of landscape poems before that book, and actually the first landscape poem was “Landscape with Sex and Violence.” And it was this big, freeing poem for me because it was everything I wanted to do with my first book, but was too scared to do. I wanted to write about sex and violence and about how sex is enjoyable but also sometimes tied to violence and I decided just to do it because I had just written a book and I didn’t have to do anything with this new poem. And the next poem I wrote was “Landscape with Smut and Pavement.” I don’t remember the order after that, but I remember those two, and saying maybe I can do something with this. I don’t know if that answers your question.

Hah, it does.

But I knew I wanted that as my title pretty early on.

It’s a great title.

Thank you.

How do you think, then, that people get over the fear of writing something?

It’s so hard!

Hah, offer advice now!

I mean, writing in general is hard. And I’m a very shy and bashful person sometimes. I was in my late 30’s when my first book came out. I waited a long time. I don’t know how you get over it. I think I started writing these more explicit poems when I didn’t think about anybody reading them. So that’s maybe one way to do it. You don’t have to publish your work. It’s not required.

Sure.

And then there’s that anger thing. Anger does drive a lot of what I do. I know I sound a little unhinged here, hah. But I told myself that people needed to read this, needed to know what it’s like to move through the world in this body, to know what’s done to the female body and how it’s perceived. And so I think as I was publishing individual poems, I felt okay about it. The one time I got real nervous was when I had a poem in The New Yorker. And it was, well, a bigger audience than I’m used to. It was “Landscape with Loanword and Solstice,” which is explicitly about rape.

Yes.

And so it’s like, I know, I’ll publish that in The New Yorker, and then millions of people will see it! And that was a little weird, and I got some weird people responding to it.

I can’t imagine.

I started not to feel comfortable. I mean, I was super happy it was there. But yeah, this is why I’m so fucked up. Because part of me felt really exposed and uncomfortable, and part of me was like, fuck yeah, everyone should read more poems about rape. I’m always two minds. And none of this is answering your question.

I mean, it’s an impossible question.

I mean, I think just maybe write it and it doesn’t have to be published. I’m not a super ambitious person in that way. My goal has never been world domination through publishing my poems. So I think maybe don’t expect to publish until you’re ready to, but then, I mean, I don’t even know if I’m ready honestly. I’m a basket case over here.

I think we all are. But I’m thinking about that point about you not being ready – because this is such a gut punch of a book, like you don’t pull any punches, which I know is a cliché thing to say. But it’s not just one or a few poems about sex and violence. It’s dozens and dozens of poems about sex, violence, rape, abortion. And it can be uncomfortable.

Hah, I’ve been called relentless.

That’s a great word to describe it! Because I remember first getting it, and I sat down and had a few hours to read, and I figured I would be able to move through a good amount of it in that time, but I had to sit with a few poems and just be in them and recover. Which is the beauty of it.

Yeah. I mean, this is not a thing of beauty, but it is definitely the book that I needed to write, to get out of my system. There was nothing else I wanted to write about in that way. Those are the topics I’ve been consumed with always, and particularly in the last five years, and I think part of that is because I’m so removed from the trauma of it – except for the street harassment, and Donald Trump. I sort of, at this point, aside from the fact that I’m terrified that my daughters are going to read this book, I don’t really give a fuck if people know this stuff about me. I’m like, whatever. This is many women’s lives.

Sure.

And I’ve been through so much trolling, with both the first book and through my work with VIDA, that I’m just like, bring it on. I don’t know what will happen with this book, though, because people are really fucked up.

They are. I mean, my hope is that it allows for more books like it to come out. Not that I want a world where people are only writing books that respond to trauma, but this book is one of the first books that I’ve read – ever or in awhile – that engages as relentlessly as it does with trauma.

Thank you.

Are there other books too? And other writers that you maybe looked toward while working on this.

You know, this is a terrible thing about me. I have a hard time consuming media and literature that is about sexual violence.

Sure.

But I want everyone to read this book about sexual violence that I wrote!

Hah.

I mean, I totally understand if people can’t read it. My trouble with it is that because I am a trauma survivor, I get triggered by things unexpectedly. So I have to distance myself from that.

Of course. So what do you like to consume? Who are you reading now?

Erika L. Sanchez has a new book out, Lessons on Expulsion, which is really fantastic. I am super excited about it. And Khadijah Queen’s I’m So Fine! I keep telling everyone to read that.

I’ve heard great things about both. What I also meant to ask – the last poem, the long sentence about Los Angeles. It almost seems like anti-poetry in a way. Where you’re expecting metaphor, or confession, and you say that it isn’t about the cage, or the bird getting out of the cage, that it’s simply about you being alive. I’m wondering if you could speak toward how you wrote it, or what you were thinking of with it. Obviously that’s a conscious choice to put it at the end, and it’s one of my favorite poems in the book.

I was pretty happy with it!

I loved it! That it’s all one sentence. I love how direct it is.

I was getting to the point where I was pretty tired of myself. Which happens a lot. But I just mean in terms of this book. I was feeling that pretty hard about the book. I was like Jesus, Lynn, shut up, everything you write does not have to be about sex and violence. So I decided to wrap it up, and what I wanted to get at in this poem was sort of what you say, that all of this is real, not artifice, that it deals with actual events. It’s also the only time I used the word “rape” in the book, which I hadn’t done before. And I don’t know – I also wanted to see if I could write a poem that was just one sentence.

Hah, right. It feels both like an ars poetica and also an anti-ars poetica, and it works so well as a last poem, because you’ve read all this poetry about trauma, and you’re expecting more poetry, but then it’s like, did you forget that this was real? And if you didn’t, well, fuck you.

Hah, yeah. There’s a lot of fuck you in the book. I spend a lot of time addressing this imaginary person who is reading the book and perhaps finding it titillating. It seems so grotesque, but I’ve had people – men only – who have told me that my poems turn them on. And if it’s just a poem about sex, well, whatever. But like, really? These rape poems turn you on? But I also recognize that that’s part of the media we consume.

Yeah, of course.

Like if you look at shows like SVU, you know?

It can be trauma porn.

Yes, it’s totally trauma porn! The rape victims that are represented in TV are almost always gorgeous and half-naked and statuesque. They’re not, like, a 79-year-old woman, or a kid. And I wanted to address that kind of reader in an antagonistic way, which is like a little fucked up now that I think about it.

Hah.

I’m such an asshole. But also throughout the writing of the book, I was also dealing with a lot of trolling – for the first book, which isn’t even that explicit!

Yeah, that’s odd.

Yeah. So I was oftentimes writing towards those readers. There’s a lot of “you.”

Sure, I recognize that now.

But also I don’t always know what I’m doing. I can be totally winging it.

I think we all are.

Yes.

To take a turn here – do you think poetry should make people feel uncomfortable?

That’s a good question.

I feel like all my questions are unfair.

Hah, but no, I don’t think it should make people feel uncomfortable. I think it can. It’s fine to, and I think it’s often important that it does, and I think that poetry gets at us in a way that other things don’t.

How so?

As soon as I said that, I thought, maybe that’s untrue. Because I feel so moved lately by Twin Peaks. I don’t know if you’ve been watching that.

A little bit. I’ve mostly just noticed a lot of animosity about it.

Really?

Well maybe animosity is the wrong word, but I’ve read a lot of hot takes about it.

I love it.

It feels to me like David Lynch is finally being as free as he wants to be.

Yeah! I feel like everything in his career so far has built to this moment. There are shades of everything that he’s done. It’s genius. I was texting my husband about it, because he was out of town for two episodes, and there’s an episode with Laura Dern, where she’s emoting in a very Laura Dern-ish way, and the way that Lynch gets to genuine human feeling while also going off the wall, in no way straightforward at all – that is what, I think, poetry does.

Sure.

And that is why I love Lynch so much. Or the way he plays with sound, like the constant buzzing somewhere. I have real sound sensitivity, so I’m very moved by sounds in mostly bad ways. But I feel like Lynch captures that so well, so it’s not just poetry that does that, but I think that poetry is trying to do the same thing. And I think about Lynch too, because the original Twin Peaks came out when I was a teenager, so it was real formative to me.

I’m thinking of Blue Velvet – where it opens on the guy watering his lawn, who then collapses. And then it zooms in on the grass, and it keeps zooming in, and it gets louder and louder and louder.

It’s really something, isn’t it?

It is. And I’ve always felt with him that he gives himself a lot of permission to do what he wants to do.

Yes.

When I work with kids, I’m always saying that. I’m always trying to get them to a place where they give themselves permission to do the weird things they want to do.

Yes! I feel that very strongly. I think, well, two things here. One, going back to David Lynch, there are some issues. I mean, he’s a male filmmaker who objectifies women and glamorizes violence quite relentlessly. So I’m not uncritical about it. But there is a way that he constructs his art that I feel very akin to.

Sure.

As far as giving yourself permission to write – when I’m teaching, I always tell my students to write the thing that, if it’s not going to scare them, it’s going to scare me. Like, freak me out. Write something that freaks me out. Because I feel like there’s so much pulling back all the time. And I don’t even mean for you to write the thing that’s some deep dark secret or something shocking in some conventional sense. It doesn’t have to be that. It can be something like: I didn’t cry when my dog died. Something like that. Give yourself the freedom to say the thing that you wouldn’t say.

You’re already breaking my heart.

Hah, but yes. I feel like that’s the book to me. Going back to that line “I’m just going to tell everyone everything that’s ever been done to my face” – like, I really do mean that. And what’s crazy about that is if someone said, hey, tell me more, I would say no. That’s awful and dark and personal. But yet somehow when I was writing this book, I was like, sure. I don’t know. Do you feel like that ever when you write? I feel like I’m going into my other personality.

I do. What’s interesting to me is that you hear a lot of people say that writing should be hard. I know we mentioned that earlier, but I think we were talking about the simple fact of coming to the page, and dealing with feelings like fear. But you hear some people say that the act of writing should be hard, and masochistic, almost. Which I don’t necessarily agree with. I actually really disagree with that. I think it can be a myth.

Yeah! It’s not hard for me.

I think there are things to write about that are hard. And I think for some people writing is a discipline and for some people it’s not. For some people, simple observation is a discipline. So I agree. When I’m writing about difficult things, in the act of writing I’m not thinking about the consequences of writing such things.

Yes.

And I think it’s hard to get to that place. Or hard to realize how you got there.

That’s what it is. It’s so hard. That’s why it’s hard for me to talk about writing. Because I don’t know how the hell I do it.

Yeah! Because I have these moments where I’m writing an essay or a poem, and then it’s almost like I snap out of it. And I can’t remember how I wrote the lines in front of me. And it’s weird!

It’s really weird! And it sounds so pretentious, right?

It does, it does.

That’s why teaching often feels like a sham. Because students will ask what I do in my poems, and I’m like I don’t know. But I don’t know how any of it happens. It comes out. And then I get to shape it. There’s a lot of instinct. Like really, I’m going to say that? Okay, I’m going to say that. I think you really do need to give yourself permission just to be free. And I’m sure it is hard for people, and some really wonderful writers find it hard, but things are different for everybody. I don’t know if I find it hard. I mean, I love it. I feel like it’s almost a high. When I’m writing and it’s going well, I feel high. So I love that. That’s not hard. Other aspects are hard. The “business around poetry” is hard. That is hard.

Yes, it is.

That’s hard. That’s uncomfortable and difficult. But the actual writing is the best part of it. Lots of people want to have written and not be writing. I don’t feel that at all.

If I could be caught up in the web of writing for 24 hours, that would be dope.

That would be so great! Because my time is so limited, writing just feels like a real gift. Like, I get to write and it’s going well? Wow. And also this whole write every day thing can come from a place of real privilege.

Hah, yes. Sometimes I wonder what we’re all doing. Like I’ll be on Twitter, which is essentially a giant community of poets talking, which is great but also weird. And I want to know: what is everyone doing right now?

To me, social media is like a smoke break, because I don’t smoke anymore. All these things I’ve given up.

I know! Cheese, cigarettes.

Hah, it’s like, what do I get! But anyways, I’ll be working, and then I take a break and go over to Twitter, and people are being assholes to each other, or they’re posting something beautiful. But either way, it’s some kind of mind break. I think Facebook is a little more of a shit-show than Twitter.

Yeah I’m off Facebook, and I do not miss it. It’s funny how you can sort of construct your own personality on social media.

Yeah, it’s a strange thing. I tell everybody that I’m really actually quite shy, but they don’t believe me. This is why the 90s poetry scene was so difficult for me, because there was no social media. I’d go to parties and wouldn’t be able to talk to anybody. Social media is good for shy people.

It is. I’ve always felt that about poetry. That it provides a voice for someone who might not have wanted to make their way through a party.

Yes. I think it levels the playing field for those people, like me. And it eliminates the tastemakers. Or – I shouldn’t say that – it expands the tastemakers. Because you have your Twitter tastemakers, those who people are paying attention to what they like, who they follow. But these are different. They’re no longer the five white men who decide who wins awards. It’s a different crowd now. This is my optimist side.

I mean, there’s a lot of exciting things happening in the poetry world.

Yes. I feel like the world has opened up a little more because we’ve demanded it to. And I think VIDA can take some credit.

I think VIDA can take a lot of credit!

Hah, I hope. But I think there are a lot of groups working towards this, and I think things are changing. But then sometimes, though – there was a Facebook thread this morning where people were talking about how 80 to 90 percent of what they happen across – like they pick up a poem, flip to a page in a journal – 80 to 90 percent of it they don’t like.

Wow.

And it was mostly white men on this thread. I wanted to jump in, but I pulled back. But I still can’t get it out of my head.

I’d say that – and this is very subjective – but it’s almost always white men who initiate and sustain conversations about things like what makes good art.

Yes! It seems so coded to me.

It does. And I’ve been guilty of this. When I was getting my MFA, I became close with a small group of friends, and a lot of our time together was spent drinking and smoking and talking about what we thought was good art.

If you can’t do that then, what are you going to do?

Right. And that was fun. And I think those are fine conversations to have in your insular groups of friends, to sort of shoot the shit and debate your own subjectivity.

Oh, absolutely. I was recently reading a bunch of submissions for a contest, and I honestly can agree that 90 percent of them, I didn’t push forward. So on the one hand, I do understand that 90 percent of what comes across a table is not necessarily the best. But also, this wasn’t about submissions. It was about just happening across poetry. And I think maybe people need to just take a step back, and try to be more openhearted. Maybe I’m just a polyanna. Maybe I just want everybody to be happier.

Devin Kelly earned his MFA from Sarah Lawrence College and co-hosts the Dead Rabbits Reading Series in New York City. He is the author of the collaborative chapbook with Melissa Smyth, This Cup of Absence (Anchor & Plume) and the books, Blood on Blood (Unknown Press), and In This Quiet Church of Night, I Say Amen (forthcoming 2017, CCM Press). He has been nominated for both the Pushcart and Best of the Net Prizes. He works as a college advisor in Queens, teaches at the City College of New York, and lives in Harlem.

This post may contain affiliate links.