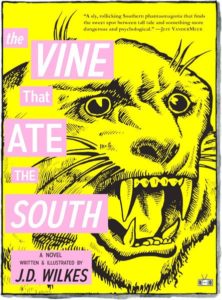

Two men ride into a haunted forest on ten-speed Schwinns, searching for a vine-choked house and hoping to return again without falling victim to the Rip-Van-Winklesque curse rumor says lies on the woods. One is a mixed-race, “foul-mouthed,” “hillbilly” “anachronism” who survived a childhood bout of rabies due to his Native American grandmother’s heirloom magic stone; the other, our narrator and the one whose quest it is, is on a mission to prove his masculinity to his “One True Love” and perhaps find a father figure (or at least Jesus). The Vine That Ate The South is more conversion narrative than odyssey, and more tall tale than either, filled with a twisty, tongue-in-cheek lyricism that calls to mind a Weird Twain.

It’s no stretch to call this book lyrical, even though the word gets tossed around in literary reviews like a hacky sack. After all, J. D. Wilkes is best known as the founder of the rockabilly band Legendary Shack Shakers. The lyrics of their fast-tempoed murder ballads and other folk tunes can, in fact, be transposed with the poems found in Wilkes’s novel, like “Blood on the Bluegrass.” The LSS’s discography reads like a soundtrack to the novel, or perhaps the book is a novelization of the discography: cause and effect are unclear, here, but the connections are indisputable. There’s “Sin Eater,” “The Buzzard and the Bell,” and “Old Spur Line,” and that’s just to get you started.

The Vine That Ate The South would be enjoyable even without this musical connection. Yet the novel sometimes feels as much like a shaggy dog story as a tall tale: the tale, like the protagonists’ journey, meanders into ditches and digressions, only to be jerked back onto the road by the structure of the quest. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and it’s likely that these digressions are what call to mind the “Homeric” description. And there’s always the vine, lurking in the woods, waiting to consume the travelers the second they stop to rest.

The eponymous vine is kudzu, of course: that plant so integral to Southern mythology and indeed, to the nation’s mythology of the South (two very different things). Kudzu is to the South what eucalyptus is to California: an imported plant that loved the conditions of its new home so much that it rapidly outstripped the use and limitations its human introducers intended (in the case of kudzu, to ornament porches and prevent soil erosion). Yet eucalyptus doesn’t carry the symbolic weight of kudzu; perhaps a better comparison would be the palm tree, even if the latter never acquired quite the same level of biological success. For Wilkes’s narrator, kudzu is biblical as well as apocalyptic. “It maneuvers around the urns of sleeping saints, through the soil of the biblical Sheol,” a vegetal Adversary:

If we could view a cross-section of Earth’s crust, we’d see how the woods above cannot compare to the wilderness growing underground. Believe it or not, this vast, gripping web is what footholds us to the planet. It reinforces our topsoil and gives humans a place to stand. Killer Kudzu, however, seems hell-bent on loosening these underpinnings, weakening our purchase, and sending us all flying into outer space. . . . not long after the footprints of man have faded into dust will Kudzu and all the other green things of the world join forces to stake back their claim. Like mold overtaking a corpse.

The threatening animatedness of kudzu — its rapid growth, metastasized in Wilkes’s novel into a plant that can kill with intent — gets projected onto all plant life, realizing the pun inherent in a garden plot. Kudzu is simultaneously “just” a vine and more than a vine: a symbol of Nature’s violent reclamation of territory, a visual shorthand for a post-human world, and an allegory for the inevitable failure of human control. (The plants in Einar Oberg’s Urban Jungle Google street view app don’t appear to be kudzu, but they might as well be.)

The Vine That Ate The South is about one young man’s search for answers, or perhaps validation, in an environment that offers little beyond horror. Yet that horror is as absurd as it is awful: larger than life and more spectacular but also, at its core, growing out of little more than the usual human desires. There’s love, friendship, music, and a touch of the divine, all in a grungy, gothic, but nonetheless hilarious little book.

Eleanor Gold is a graduate student and Reviews Editor for Full Stop who is currently trying to turn her love of weird, squishy animals into an applicable methodology for cultural studies.

This post may contain affiliate links.