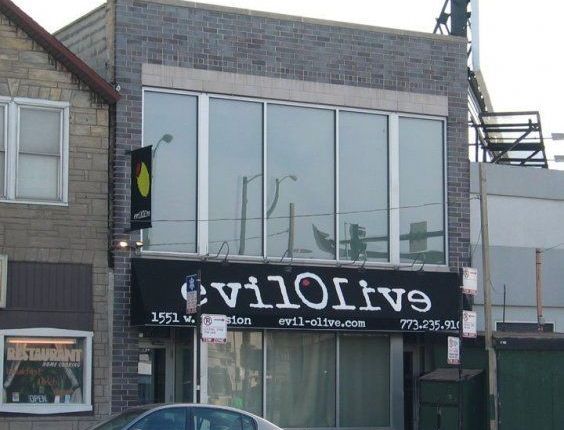

In the last few days, a series of articles appeared in the Chicago Reader and Chicago Tribune detailing Cook County’s pursuit of $200,000 apiece in back taxes from Evil Olive and Beauty Bar, among others. The two bars owe because of a heretofore unenforced “amusement tax” by the county, which is levied onto events like Bears and Bulls games. Per county code, sub-750-capacity venues that charge ticket prices for “in person, live theatrical, live musical, or other live cultural performances” or “any of the disciplines which are commonly regarded as part of the fine arts,” are exempt from the tax. But apparently, according to the county, “Rap music, country music, and rock ‘n’ roll” do not fall under the purview of “fine art.”

In the last few days, a series of articles appeared in the Chicago Reader and Chicago Tribune detailing Cook County’s pursuit of $200,000 apiece in back taxes from Evil Olive and Beauty Bar, among others. The two bars owe because of a heretofore unenforced “amusement tax” by the county, which is levied onto events like Bears and Bulls games. Per county code, sub-750-capacity venues that charge ticket prices for “in person, live theatrical, live musical, or other live cultural performances” or “any of the disciplines which are commonly regarded as part of the fine arts,” are exempt from the tax. But apparently, according to the county, “Rap music, country music, and rock ‘n’ roll” do not fall under the purview of “fine art.”

Unless some more inclusive language makes its way into county code, the implications are grim: many of the places that would have to pony up don’t charge customers very much for a ticket (the most I paid to see a show at a club while I was living in Chicago was $30), and this kind of financial strain would make it difficult for them to keep hiring the kind of acts that are keeping the Chicago music scene vibrant. The county seeks just a 3% tax on ticket prices, but much of he financial strain would result from the massive amount of back taxes the county seeks. Beyond money, though, the message Cook County sends in enforcing this tax is that most music being made is little more than a hobby, with no more artistic merit than a sporting event.

Given the trajectory of rock music, hip hop and rap, and dance music1 over the last half century, this is a vexing notion. While many of these genres began as countercultural movements, at this point they now occupy similar cultural spaces to that of the kinds of music Cook County sees as “fine art.” In 2014, the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art hosted an exhaustive David Bowie retrospective, including the Disappears playing a cover of Bowie’s Low album on the same stage where I’ve seen the International Contemporary Ensemble play several concerts. Frankie Knuckles’ record collection is housed at the Stony Island Arts Bank on the South Side. Elsewhere, Jay Z has played Carnegie Hall.

Knuckles, Bowie, and Jay Z are cultural institutions by this point, but this status doesn’t ipso facto confer legitimacy onto the glut of lesser-known acts making music that sounds like them. Instead, they act as signifiers of a legitimizing of the musical traditions that act as a bedrock for popular music of many stripes. Pop music is the furthest thing from ahistorical; as DJs sample tracks, they footnote their histories and attach themselves to their samples’ narratives. Rock bands often describe themselves using genres or bands as shorthand for sonic and narrative signifiers. When a band describes themselves as a Psychedelia or Punk band, they do so as a way to tether their sound and aesthetic to a historical schema. In effect, classical musicians and composers operate on similar terms. Artist and ensemble bios are often rap sheets of mentorships/apprenticeships, and professional and academic credentials, each of which links the artist’s back story to an established tradition. This kind of accreditation from without is more commonplace for classical/contemporary groups, but there still seems to be a pecking order when it comes to an unestablished string quartet, a four-piece band, and one person with a set of turntables.

Part of that has to do with skill. The technical demands of concert music are undeniably more stern than those of playing rock music or DJing. I taught kids how to play rock music during my last year in Chicago, which meant that I basically focused on teaching the barest fundamentals of music. I did not have to teach phrasing, dynamics, bow/breath control, precision, or intonation to the degree that I would have if I were teaching them how to play Bach, or Elliott Carter. But that argument only goes so far; technical proficiency is obviously important, but its importance is miscast. Technical proficiency in music is but a means to the end of expression. It’s why Miles Davis is so compelling (his technique is expressive), and Yngwe isn’t (his technique is impressive). Playing rock music — and making music out of samples — requires just as much finesse and command over an idiom as classical music does. Most of the pop idioms, though, have their roots in black music. Rock music is and always will be a purloined aesthetic (the examples of white artists ripping off black ones could take up hard drives), and you can trace any number of paths from the Second Line and Creole bands of New Orleans to any music that grooves at all. In Cook County’s relegating of these musics to amateur status, they’re devaluing an artistic narrative in which black artists played a seminal role.

This isn’t Chicago’s first time taking a position that undermines popular music. An infamous episode that comes to mind isn’t one that the county spearheaded, but a crusade led by a rock DJ named Steve Dahl. Dahl was fired on Christmas Eve in 1978 from WDAI during the station’s push to a disco-centric format from a rock heavy program. In spite of rock music’s tonal language owing a debt to that of the blues, many of the bands in rotation in the ‘70s were predominantly white men. After moving to WLUP (The Loop), Dahl garnered a following behind the Disco Sucks banner, culminating in the the Disco Demolition Night in 1979. Dahl and White Sox Owner Bill Veeck (a man who the Reader referred to as the PT Barnum of Baseball offered 98-cent admission to a Sox-Tigers doubleheader to fans who brought disco records for Veeck and Dahl to demolish between games. While Dahl has contended over the years that it was strictly a promotional stunt, it’s hard not to read the racism and homophobia of demolishing disco records.

The cultural implications are certainly insidious, but the impetus for this tax and crusade for back taxes has more to do with greed.

Cook County isn’t really interested in some kind of philosophical discussion about the nature of high art. It’s acting as a tax collector, of course, not a cultural gatekeeper. It could try to extract funds from the opera, symphony, or moneyed fine-arts patrons with say, a financial transaction tax, but instead it decided to play the bully and shake down the little guys — the PBR-stained bars and divey dance clubs — for their lunch money.

Still, this kind of victimization could keep venues from being the kind of spaces where this kind of art can grow, thrive, and continue to attract communities around it. Counterculture or not, popular music still creates an environment where people can meet like-minded people, and artists can explore avenues of self-expression that enrich the community. The venues that would be taxed provide a service, as they make the city a more welcoming place for those of us who find solace in this kind of music. It’s a scary thought that they could be at all compromised.

[1] All of which, for me, fall under the umbrella of “pop,” so you’ll see me use that as an umbrella term.

This post may contain affiliate links.