His sitting room was full of book and records. A moment’s looking showed that the books were a serious collection of twentieth-century American writing in first or very early editions: Al had been buying or collecting, for more than forty years. His jazz records (worn sleeves standing upright, filling many shelves) were equally valuable. Jazz was one of his passions, and he was a noted writer on the subject….

He was a man of enthusiasms, easy to be with, easy to listen to. His life seemed to have been a series of happy discoveries.

— V.S. Naipaul description of Albert Murray’s apartment in “A Turn In The South”

Major critics do not achieve that status by possessing impeccable taste; it is not the highest calling to have the cleanest scoresheet. Indeed, there is something foppish and epicurean about striving to merely have all the right opinions at the right times. Instead, the major critics are the ones with the strong opinions, the ones who aren’t receptive to every new experience, the ones whose defiant inflexibility may bend the culture towards the future. Major critics have major themes, which ballast their writing and allow them to rise above merely being tastemaking. Just as Edmund Wilson had modernism and Trilling had the liberal imagination, Albert Murray had the blues idiom.

The blues, as explained by Murray, are not the wails of lamentations, melancholic outpourings for the woebegone and disconsolate. Au contraire, the blues are intended to dispel such feelings, not wallow in them. The blues constitute a battle against chaos and entropy and in their broadest interpretation, lie at the heart of any artistic endeavor. But this is not merely art as entertainment, though it must certainly be that as well. This is art as ritualized survival technique.

Though Murray has produced several great books, he doesn’t have a magnum opus per se, a single definitive work which captures the breadth of his talent and firmly anchors his oeuvre. (This also partially explains the relative lack of attention it has received.) The Omni-Americans, his debut collection of social criticism; Stomping The Blues, his exploration of blues-derived musical expression; and South To A Very Old Place, a sui generis and largely unclassifiable travelogue-memoir, have the strongest claims to being his best. (The slim volume The Hero and The Blues is a darkhorse contender for this title.) There are many paths into Cosmos Murray; Murray produced work in nearly every genre except (to the best of my knowledge) the libretto. If nothing else, Murray can be credited with championing a new critical language. Just as James Baldwin combined Henry James and black church, Murray combined High Modernism with the jukehouse.

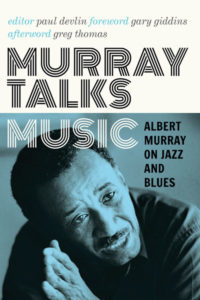

In lieu of a more obvious entry point, Murray Talks Music is probably the single best introduction to Murray’s thought,  a fitting forerunner to the forthcoming Library of America edition of his nonfiction. This is not damning with faint praise. The interviews here are not tossed off miscellany of minor significance to all but the completists. In his introduction, editor Paul Devlin argues that Murray was a master conversationalist whose talking was as valuable as his writing. On the basis of these interviews, which display the catholicity of his interests and the depth of his insight, which show him skipping and riffing, effortlessly shifting from the slangy and demotic to the upper registers of high theory, Murray was blessed (as they would say in one of those downhome churches) with the gift of utterance.

a fitting forerunner to the forthcoming Library of America edition of his nonfiction. This is not damning with faint praise. The interviews here are not tossed off miscellany of minor significance to all but the completists. In his introduction, editor Paul Devlin argues that Murray was a master conversationalist whose talking was as valuable as his writing. On the basis of these interviews, which display the catholicity of his interests and the depth of his insight, which show him skipping and riffing, effortlessly shifting from the slangy and demotic to the upper registers of high theory, Murray was blessed (as they would say in one of those downhome churches) with the gift of utterance.

In the interview which opens Murray Talks Music, Wynton Marsalis, a Murray disciple and co-founder of Jazz at Lincoln Center asked (possibly with a wink and a grin as he grooved it down the middle) : “Don’t you think the belief that everything is always in decline is just part of that natural pessimism? There’s always a belief that the end is near, and these days are always much worse than the days of yore—”

Murray’s answer is as close we’ll get to summation of his central idea: “…the spirit of jazz, the spirit of the blues and jazz, is always to counterstate adversity and negative feelings about the outcome of things….Whereas the great art forms of the past have dealt with these aspects of human life—like Greeks had separate forms—Greek tragedy, Greek comedy, Greek satire. To me, jazz is a form which includes all of that: it’s tragedy, comedy, melodrama, and farce. So, in my book The Hero and the Blues, the ultimate thing is straight-faced farce. That is life is a low-down dirty shame that shouldn’t happen to a dog, entropy is always threatening you—how do you get with it?”

Despite the name of the collection and the fact that one of the interviews was edited to suit this musical focus, Murray’s conversations range far and wide. Many of these conversations sprawl further than music into literature, social criticism and almost everything else. (What know they of jazz who only jazz know?) The primary thing about the blues idiom is that it is a sensibility: it can be manifested in any art form, as Murray himself demonstrated.

The interviews can loosely be classed into two main categories. The first are the ones which—though centered on music—expand to provide broad overviews of Murray’s ideas on art generally. These include the interviews with Wynton Marsalis, Greg Thomas, Robert O’Meally, and the two interviews with Devlin himself. The other interviews are more specifically focused on music, with greater technical and historical details. These include interviews with Dan Minor, Billy Eckstine and John Hammond, which were part of the research for Murray’s biography of Count Basie, Good Morning Blues; and the transcript of a radio show with critics Stanley Crouch and Loren Schoenberg discussing the music of Duke Ellington. However, the most historically significant interview in this category and arguably the most significant of the entire book would be the interview with Dizzy Gillespie, the full version of a conversation which originally appeared in a highly abridged version in Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine in 1986.

Greg Thomas comments on the conversation between Murray and Dizzy Gillespie in the book’s afterword. He notes that while Murray’s musical references were mainly centered on the United States, Gillespie’s view was more expansive, encompassing the the entire Western Hemisphere. (Though it was Murray who was familiar with Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos and purchased bongos in Cuba.) This is mirrored by Murray’s intellectual references which seem curiously indifferent to other thinkers from the hemisphere who developed similar ideas.

This is somewhat understandable. When Murray launched his career, it was fashionable, as it is now, for intellectuals and activists to articulate their grievances in terms which seek to disassociate them from the United States (that famous James Baldwin line notwithstanding), ironically embracing the worldviews of their oppressors. He rejected a narrow essentialist definition of America, or of the people he continued to defiantly refer to as Negroes, and took pluralism for granted. He did not primarily think of black people as victims of America but as quintessential Americans, those by whom the very term is defined. Murray rejected this tout court; for him, America was a possession, not position. America was a project, a conscious invention of intellectuals and constantly subject to debate and renewal.

In the works of Murray and Ellison, “the lower frequency” or bass clef is often used as a metaphor for the South, on which the rest of America is built. But the South could be seen as part of a wider plantation society, which stretches from the James River through the Antilles and down to Bahia. This America is distinct from the European settler colonies which constitute most of North America and the Southern cone of South America, nor is it the indigenous America of Mexico, Central America and the Andes. This America is truly New World, where Africa, Europe and Asia converged to form a new civilization.

In this larger context, Murray and Ralph Ellison could be placed in an eclectic group: Édouard Glissant, Rene Menil, Antonio Benítez-Rojo, Alejo Carpentier (see Devlin’s essay on him), Lloyd Best, and even C.L.R. James, among several others. These writers instead of exclusively embracing their diasporic identities as a way of rejecting European hegemony, instead grounded themselves argued that the realities of life in the New World for a hybridised, creolised identity. (It would be useful to juxtapose James’s conception of cricket as laid out in Beyond a Boundary with Murray’s conception of jazz.) In this regard, Murray’s pluralism was somewhat impinged by domestic concerns.

Murray did respond to a question about Derek Walcott posed by Thomas; given that both had collaborated on projects with Romare Bearden, it seemed that he was likely familiar with his work: “I get the impression that he wants to create an image of ambivalence because he doesn’t know whether he’s British or African. But he isn’t African—he’s West Indian. I didn’t go through all the poetry. I have quite a bit of it and I plan to. I have a high regard for his level of ambition. But the thing I like best that he did is his Nobel lecture! There he comes up with a Caribbean identity that makes a lot of sense to me. “They’re not us and we’re not them, we’re not African and we’re not British—we’re Caribbean!”” Murray went on to praise Walcott for what he termed “accepting the challenge” of Saint-John Perse, a Guadeloupean béké who like Walcott, won the Nobel Prize for Literature. An expanded view of what constitutes “America” would have yielded some fruitful insight from Murray, had he been inclined to do so.

Murray’s influence, even if not as strong as it should be, has been persistent in American culture, most obviously via his role in providing the ideas for Jazz at Lincoln Center but also in the literary world, with acclaimed writers like Charles Johnson, James Alan McPherson, Elizabeth Alexander and Ayana Mathis all acknowledging the great influence Murray has had on them. The three writers contributing to Music Talks Music give indication of how Murray’s influence has reached across generations. Gary Giddins, born in 1948, met Murray by attending his jazz criticism classes in the seventies; Greg Thomas, born in 1963, was introduced to Murray by reading Stanley Crouch’s column in the Village Voice, as I would many years later, albeit via a secondhand copy of his collection Notes From A Hanging Judge; Paul Devlin, born in 1980, discovered Murray by reading Ellison and then reading Trading Twelves, their collected letters, when it was released.

The process of canonization is a tricky one, even for writers who received more attention than Murray did. Often it is the grandchildren who are able to grasp something the parents were too close to see. The moment also matters: Black Lives Matter was a reminder that James Baldwin still mattered.

Murray’s achievement, book by book, was the articulation of a sensibility. This is the sort of achievement which takes a while to come into full view. With his ascension to the Library of America, a new audience will see the full scale of Murray’s achievement. It’s appropriate that at the end of Murray’s century, when life is particularly low, dirty, and shameful, to have him remind us to pull it together and stomp.

Matthew St. Ville Hunte lives in Saint Lucia.

This post may contain affiliate links.