[New Internationalist; 2016]

[New Internationalist; 2016]

Trans. Cindy Kite

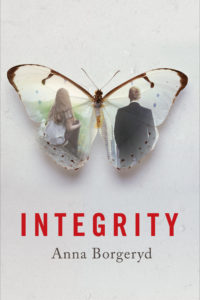

A dashing Swede from a successful business family has floated on the great ship Privilege for 24 champagne-doused years. That ship begins to sink, however, as Peter refuses to take control of his life and the family business. Decked out in the latest Louis Vuitton, Peter exemplifies the consumptive Western lifestyle that Anna Borgeryd’s Integrity critiques. Luckily for him, Peter’s unusual college roommate Vera, a field nurse turned feminist economist, offers an alternative approach to the world. While Peter at first derides Vera for her lack of superficial charms, he reevaluates his elfin roommate after glimpsing her trying on a silken ballgown. As love-struck Peter attempts to gain Vera’s good opinion over several hundred pages, Vera learns to prioritize self-care over care-taking and to deal boldly with the familial problems that have plagued her life.

Vera ostensibly hates clichés, but her author definitely does not. With 500 pages of a reformed rake plot peppered with economic philosophy, Integrity feels more like one of Samuel Richardson’s 18th century tomes than like your average 21st century novel. The romance plot offers a too-familiar course of twists and turns, but you might learn a pointer or two about green economics as the lovers’ exchanged looks heat up. Apparently, it’s a slippery slope from externalities to intimacy for Swedish economics undergrads.

Part Danielle Steele, part greened Adam Smith, Integrity uses a conventional romance narrative to seduce readers into concerning themselves with the complexities of the modern globalized financial system and potential green economic reforms. Although this iteration of the eco-romance form feels overwrought with repeated references to the Titantic (romance + too big to fail) and words of inspiration from a semi-mythic South American indigenous tribe, the vision behind the budding genre has potential for bringing new audiences to environmental issues. How can art give shape to the nebulous, evasive world of global finance that drives our current environmental destruction? What would convince us to pull each other from that violent path? Borgeryd uses the microcosm of the young lovers to symbolize what a change from a life of reckless waste to one of long-term sustainability would take. Rather like the socialist muckrakers of the early 20th century (think, The Jungle), Integrity employs a hackneyed romance plot to serve as a vehicle for discussing social and economic ills that wouldn’t otherwise make it to a spot on the nightstand.

Although some of these ideas of reproductive economics and structural integrity flow naturally in the late-night conversations of Integrity’s cast of economic undergraduates and graduate students, many sections of the novel become bogged down in explanations of the financial sector. These passages have an expository resonance that a romance-driven reader might be liable to skim, especially since much of the plot would make sense without the technicalities. Yet, when not lecturing, Borgeryd’s prose (translated from Swedish by Cindy Kite) is light and good-humored, emphasizing dialogue and unspoken thoughts. The novel delights in detailed descriptions of lingonberry jam and designer handbags. Integrity’s characters are personable and familiar. And, if they change in predictable ways, at least they were are given clear reasons to do so. The narration, which shifts easily between the perspectives of Peter and Vera, conveys a certain pleasing fondness for many of the characters.

As is all too common in environmental fiction, social conservatism accompanies the progressive economics of Borgeryd’s novel. Making claims to protect the long-term future at the cost of short-term pleasures often relies on unnecessarily heteronormative reproductive narratives. In Integrity, for example, homosexuality only arises as a repressed, troubling secret that festers into porn addictions or sociopathic business behaviors. Furthermore, the characters of color are tokenized by the other characters and made peripheral by the narrative — the novel implies that they are impacted by the recklessness of dominant culture, but have no recourse beyond waiting for white men to wake up, apologize, and change. Such disappointingly stereotypical descriptions pervade Western environmental literature. Rather than falling into these conventional narratives, eco-fiction needs to underscore the need for traditional environmentalism to question its own positions of privilege and provide a space for imagining non-normative paths to sustainability if it is to inspire genuine social justice.

Undoubtedly informative and occasionally spot on, Integrity breaks important ground for writers of environmental romance fiction, though it uses an imprecise tool. As this genre develops, authors such as Borgeryd will hopefully continue to develop more nuanced ways of bringing forward environmental concerns. Such novelists help us to envision social change through compelling narratives that explore the connections between the mentalities that propel our personal interactions and our global actions. As the continued debate about climate change shows, facts change opinions far less than we might wish. Increasingly, we must look to storytelling to help readers reimagine what is possible and to offer new contexts in which to understand the reality. The eco-romance genre seems particularly promising for its ability to foster emotional attachment and warm feelings related to a subject matter that is often incomprehensibly immense and terrifying.

Emma Schneider is a graduate student at Tufts University. Her research focuses on North American and Environmental Literature.

This post may contain affiliate links.