Carrie Brownstein used to be famous in one way; knowing of her and her band Sleater-Kinney was a signifier of a certain kind of feminist coolness, a vibe I wanted to wrap myself in, simultaneously a blanket and a shield. I was a little too young to have participated in the halcyon days of the Riot Grrl movement (whether or not you want to include Sleater-Kinney in the movement, the timelines certain coincided), I spent many college years expressing all my rage by screaming along with Corin Tucker’s wild melodies on their second album, Call the Doctor (which was many years old by the time I found it, but I loved it). I still channel my anger into that album, into the title lyrics of the title track in particular. Driving angry through Los Angeles, I pound on the steering wheel and tunelessly scream “CALL THE DOCTOR, CALL THE DOCTOR, CALL THE DOCTOR,” until my throat hurts. This is one Carrie Brownstein, famous among music critics and disaffected feminist youth.

There is another Carrie Brownstein now, on your television sets, or as I described her to the college-aged movie theater bartender at the Landmark Cinemas in the Embarcadero Center in San Francisco: “Carrie Brownstein is the female one on Portlandia.” His favorite Portlandia sketch, he told me, was the one where she has to break up with Chloe Sevigne (“that girl from the American Horror Story in the asylum”) at the communal dining table. I love that one too, so we could laugh about it a little bit, and then he tried to teach me how football works while I chugged my white wine as subtly as possible.

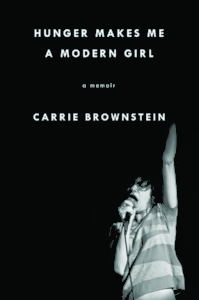

Brownstein the Rock Star is not a different woman from Brownstein the TV Star, and the line between phases in her career is blurred by Sleater-Kinney’s 2015 album release, but her memoir, Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl, still somehow feels like a return, a reunion with the Brownstein I met as a disaffected feminist youth, when I needed other disaffected feminist youths singing in my ear. With this book, instead of just listening to lyrics and trying to peer around the edges of magazine profiles and song lyrics, I have been truly introduced to Brownstein. It is so lovely to know her.

I remember the first time I heard the track that Brownstein’s memoir takes its title from, “Modern Girl.” It was 2006 and I hadn’t spent much time with Sleater-Kinney’s 2005 album The Woods, but I had tickets to Lollapalooza and I knew I would see the band there. I wanted to be prepared, so I bought the album on iTunes and listened through. In the lyrics of the song, two other things, besides hunger, make me a modern girl: happy and anger. Hunger was the right choice for the title of her memoir.

For fans of the band, the best parts of Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl are Brownstein’s elegant and detailed examinations of Sleater-Kinney’s creative process on every single one of their albums, and how that creative process evolved through the band’s lifetime. For me, that examination was one of the book’s most supreme pleasures.

Unlike Sleater-Kinney’s ’90s and 2000s-era records, Brownstein’s delivery in Hunger Makes Me A Modern Girl, is rarely raw (excluding a spectacularly raw climax, which I will not spoil). She seems, now, uninterested in rawness. Compared to our great contemporary feminist literary purges (including but not limited to Trisha Low’s The Complete Purge, Kate Zambreno’s Heroines, Sarah Gerard’s BFF zine for Guillotine, and everything that the literary journal Selfish is doing), Brown is sometimes downright gentle. She doesn’t flatter herself, but she’s confident; Brownstein gives her reader a calm openness. Brownstein invites us to her female body horror, her hospital visits, her sores and hives and shingles. And yet, she doesn’t spew. She doesn’t need to vomit to show us what’s inside her. She has the supernatural capability to unstitch her skin and show us her insides without bile or blood, a trick that, upon reading her memoir, we realize she learned through years of metaphorically vomiting and bleeding for us, the fans.

Discussing the writing process by which Sleater-Kinney’s 2000 album All Hands on the Bad One came into being, Carrie Brownstein takes stock of her own writing style, comparing herself to bandmate Corin Tucker: “My narratives were often oblique, hers direct. She was bold; I described boldness.” It’s like that thing we say about bad significant others — people will tell you exactly who they are. This new adage very nearly described Brownstein’s memoir of her Sleater-Kinney years. Perhaps the young woman Brownstein was would’ve succumbed to narrative tendencies towards obfuscation — a technique that can be effective in songwriting but sinks a memoir — but she saves herself. Throughout her memoir, which comes in at a perfect length (240 pages in the hardback edition), Brownstein is at war with her tendency towards obliqueness, occasionally falling into it, but making sure to coarse-correct later.

The only real quibbles I have with this memoir are the following. Brownstein delays an emotionally open description of her relationship with bandmate Corin Tucker a little too long. Though, perhaps, I’m just a gossip who didn’t want to wait to hear the nitty-gritty details of their breakup. Also, Brownstein frequently uses a linguistic tick I find annoying; when she mentions another famous person, she tells a story about them then uses their name as a punchline:

We missed seeing our opening act, a singer whom we were told was too afraid to look at the audience. Nevertheless, CJ said her voice and songs were stunning, that they’d made him cry. He proudly showed us the 7-inch single he’d purchased, the first one released by this artist, who went by the name Cat Power.

It was a cassette she’d been listening to nonstop, made for her by a friend, a boy she was trying to no longer have a crush on. That boy was Elliott Smith.

I used the word “quibbles” to describe these small criticisms very deliberately; they are small, insignificant, and didn’t diminish my enjoyment of this pleasurable, beautifully written memoir. No matter which Carrie Brownstein you discovered — the rock star or the TV one — you won’t really be introduced to her until you read this book. For readers who are not yet fans, start here and work your way backwards.

Catie Disabato writes a monthly column for Full Stop about the contemporary and sometimes not-so-contemporary literature she’s been reading. Her first novel, The Ghost Network, was published by Melville House in Spring 2015.

This post may contain affiliate links.