In the early ’90s, Adrian Tomine was a prodigy. Readers compared him to Raymond Carver and Daniel Clowes. Chris Oliveros, the editor of Drawn and Quarterly, first mentored Tomine by mail and then began publishing his mini-comic Optic Nerve, placing him on the roster of the growing independent company, alongside Julie Doucet and Joe Matt. Still, the flaws in Tomine’s stories were salient. He fell back on narrative tricks. He wasn’t entirely comfortable with his stripped-down drawing style. The narrations were too stylized and affected. None of that really mattered. Tomine’s stories had a terrible, emotional charge. He understood loneliness.

In the early ’90s, Adrian Tomine was a prodigy. Readers compared him to Raymond Carver and Daniel Clowes. Chris Oliveros, the editor of Drawn and Quarterly, first mentored Tomine by mail and then began publishing his mini-comic Optic Nerve, placing him on the roster of the growing independent company, alongside Julie Doucet and Joe Matt. Still, the flaws in Tomine’s stories were salient. He fell back on narrative tricks. He wasn’t entirely comfortable with his stripped-down drawing style. The narrations were too stylized and affected. None of that really mattered. Tomine’s stories had a terrible, emotional charge. He understood loneliness.

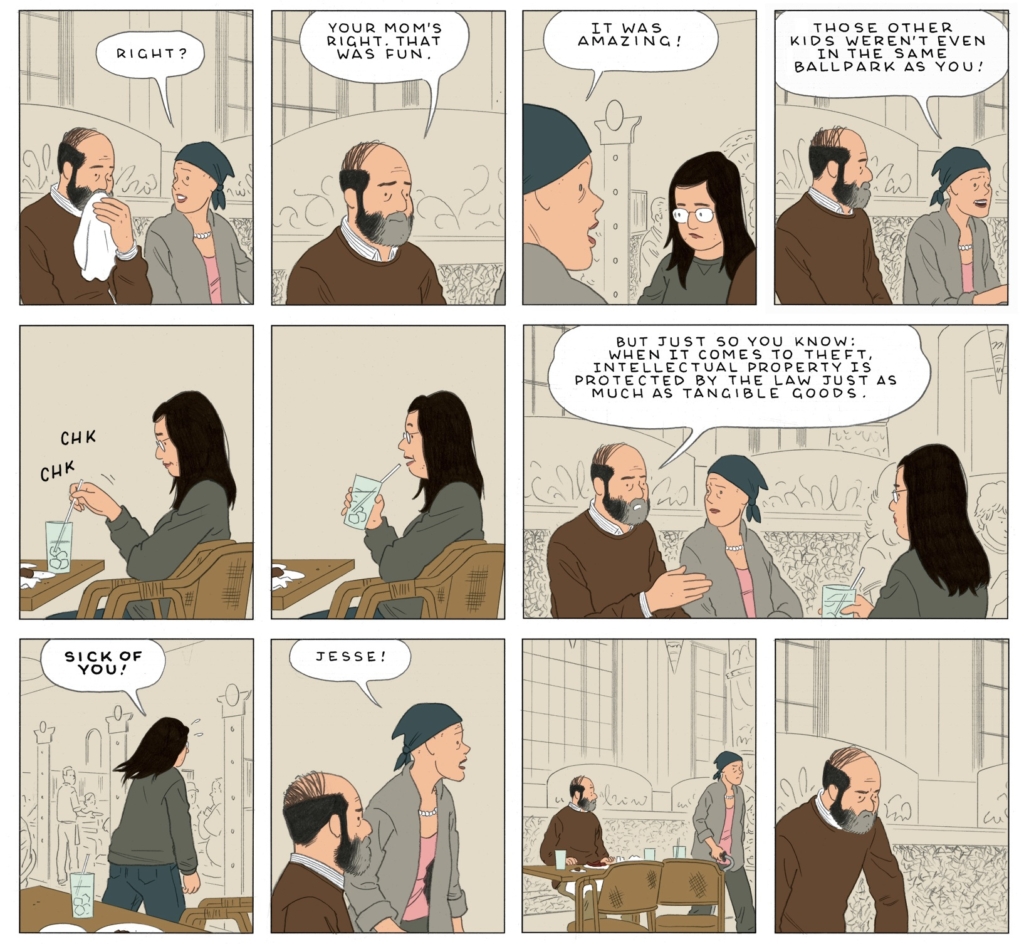

For the past decade, Tomine has been doing New Yorker illustrations, each of them sad, sophisticated vignettes of Bloomberg’s and now de Blasio’s town. In 2009, he published Shortcomings, a graphic novel that both criticized and accepted the discourses of ethnic studies. This year he has published Killing and Dying, a collection of six stories, each of which adopt different permutations of the comics medium. He structures one story as a newspaper comic strip, another as a series of large illustrations. The title story ends mid-page and confronts the reader with a sea of white space. These are brutal, tight narratives. Tomine has grown comfortable with his somber voice. At 41, he’s too old to be the voice of a generation. Instead, he has become a master storyteller.

Tomine and I met at a Starbucks in Portland in early November. He was in town for the city’s annual book festival, Wordstock.

Paul Morton: I’m not a parent myself, but I know you are. There is a more biting pain that comes from seeing your child hurt than from being hurt yourself.

Adrian Tomine: I agree. I started working on this book right around the time I found out my wife was pregnant with our first daughter. And I’ve worked on it long enough that we actually have two daughters now, a six-year-old and a one-year-old. That change in my life is probably the most significant one since I started working as a cartoonist.

Has that changed, not just your stories, but the way you draw children?

Not so much. There’re more kids in general in the stories than there were before. The change in the drawing has more to do with two things. The artistic reason is that a lot of what I was doing in this book, including the drawing style, is a reaction to having worked on Shortcomings for a long time. I wanted to do everything differently. The more pragmatic reason is that I’m just searching for a way of working that is more economical and easier so that it doesn’t take me seven years to make a book. This book was an experiment to see if I could still create satisfying stories, or if I could still have the same amount of emotion, a feeling that the characters were still alive, but with a less detailed and less complicated drawing style.

In Killing and Dying, there’s a lot more experimentation than you had before. “A Brief History of the Art Form Known as ‘Hortisculpture’” is told in the form of a daily strip, complete with full-page color cartoons on Sundays. “Translated, from the Japanese” . . . is a set of illustrations with limited narration. Are you concerned that such cleverness overwhelms the functionality?

It’s a risk. I think [experimentation] is happening a lot in comics right now and not necessarily in a bad way. There’s a lot of joy that can be derived from comics that are formally experimental or innovative. [In prose fiction], there’s a consensus of what we’re supposed to get from it. You’re supposed to get the stories and the characters. There’s hundreds of years of criteria that have developed. I think comics are still new enough. As a reader, I’m open to the idea that a good comic is not necessarily the same thing that I’m aiming for when I’m trying to make a good comic. There are great uses of the art form that are not narrative, or don’t tell a realistic story, or are not personal in the way that Harvey Pekar is, but are still great works of art.

It’s more of a danger for me, because I’m trying to tell stories about real people and I’m trying to evoke emotions. With that as the goal, there is a risk of the formal play distracting or obliterating [those goals].

Illustration Credit: Adrian Tomine/Drawn and Quarterly

Were there any precautions you made to minimize the risk?

I didn’t feel I was in any great danger, because the idea of experimentation was secondary to my main goal of just making the stories readable. I think there are some artists whose priorities are flopped. For me, I was dead set on the idea that this book would be readable for people who had grown up reading comics and also those hadn’t. There are so many cartoonists now [for whom] I’m totally their target audience . . . I’ve been reading the whole medium since I was a kid. I have all that shared knowledge and I can get those kinds of references. There’s no having to explain the framework of the art form to me.

But I was definitely hoping that there were places like this [book festival] where the people I’m meeting are not necessarily comics readers or that in a bookstore someone would pick up a book and think, “What is this weird-looking book?” That desire to connect with a broader audience, for better or worse, kept the confusion of the experimentation in check.

How much do you know about the things that are not articulated explicitly in your stories? In one of your older stories, “Bomb Scare,” we don’t know what kind of sexual congress may have occurred between the two boys, but did you know?

Well that’s a bad example, because that’s so far in my memory that I might have at the time, but now I’m struggling to even remember anything about the story. About the current ones, I’d say a lot. The downside of the way I work is that it takes a long time to finish a book. But the upside is that a lot of stuff gets figured out in my mind that I wouldn’t have time to figure out if I had a one-month deadline to bash out the story.

I think a more organized artist would do a lot of this work in notebooks. Seth figures out all these backstories of his characters and these towns and he writes it all out. I don’t quite have his tenacity and artistic ability to do the kind of work [that no one sees], but I feel like I’m doing a lot of it in my mind.

Do you know the bigger holes?

There was a time earlier in my career when I didn’t know and I was okay with that and I would just milk the ambiguity of it. At least when I was working on this book I felt differently and I felt even if it wasn’t in there I would know it in my head.

There are a lot of things people have asked me about this book that I know the answer to that, but I’d prefer not to say because I’ve already heard such different interpretations from readers that I feel like those are the opinions that matter at this point. It would be really cruel to squash those interpretations, to say, “No no no, this isn’t in Long Island. This is very clearly California.”

I feel like I heard about the incident depicted in “Go Owls” [in which a group of parents delinquent in child support payments are lured to a sporting event.]

There’s a lot. If you look it up online, there’s a lot of stories about it. It must have been some trend in law enforcement for a while.

It’s something that was in the back of my mind since I was pretty young, because it happened when I was living in Fresno, California [when I was in sixth or seventh grade]. They did a fake thing with the college football team, the Bulldogs, which everyone in the town was a fan of. I must have filed it away in my brain, because it was just marinating there for a long time and it ended up in this story here.

What was the thing about it that first hit you?

I had a strange take on that, especially for being 11 years old. It was not, “Yay, these guys who broke the law got caught.” It was that it was sad that these guys were going to a football game that they cared about and then ended up going to jail. That may have something to do with my personality which leads into how I write characters in general. It’s hard for me to feel one way about a person or a character. There’s a lot of “yes, but” conversations that go in my house about people who have done something we don’t like. My wife’s a psychologist. She goes even deeper than that. She’s incredibly empathetic and has sympathy even for people who have done the worst things in the world.

When you write about kids who were picked on in high school, you don’t present them as noble victims. They are made worse by the abuse they suffer. It becomes a vicious cycle.

I think that’s one nuance that Hollywood has a little difficulty with tapping into sometimes. I think Freaks and Geeks did a good job with that actually. Speaking from my own experience and kids that I’ve known and observed, it’s rare that someone is just randomly chosen and ostracized. It’s not always something within their control, but there is always a reason why they’ve been selected to be left out or made fun of or whatever.

Do you still have the lingering self-loathing from that period?

As with everything in my life it’s moved into a new phase, a meta phase. I’m now a parent, so I don’t think of it in terms of my own personal wounds or anything like that. But I’m really sensitive to going to my daughter’s school and seeing the kids who are sitting eating their lunch by themselves, not quite knowing how to interact with the other kids or things like that. It’s extremely heightened and it’s hard for me to hold my tongue when I see stuff like that. It’s healthier to be thinking about it in terms of actual people who are going through that stuff now rather than memories of my own life twenty-something years ago.

I think there’s a kind of work that is very common among artists between 18 and 25, along the lines of “This is my pain. This is the injustice the world has inflicted on me.”

Regardless of how extreme the pain really is.

I think there was a bit of that in your early years.

Yeah sure.

Can you remember the point when you got rid of that?

I feel like by the time I had finished drawing Shortcomings I was tired of the story I had written initially. It’s hard to say. A lot of it has to do with the circumstances of my own life changing. It also has to do with the fact that that came on the heels of 15 years of producing similar stories already. And there was an accumulation of [those stories]. I am working in the shadow of all the stuff I did previously and eventually all the annoying tics start to accumulate in my mind as a reader and then I have to move away from them.

Daniel Clowes, Julie Doucet and Joe Matt—all these people who came up when you came up in the ’90s—indulged the grotesque. You didn’t. Why?

I felt left out in a lot of ways, because at the time that was the standard by which alternative comics were measured, which is how disgustingly self-revealing could they be. At one point it was a competition about who could do the most disgusting bodily-function comic strip, whatever it might be.

A lot of it was just fascination with the abject body.

And in terms of drawing style too there was an emphasis descending from the underground of these grotesque, highly detailed bodies. For a long time, I felt very annoyed that I had this very clean and commercial drawing style. That was not really by design, but just sort of developed naturally. I was criticized for it a lot too.

There’s a lot of ways in which I feel so deeply connected to my peers in the world of cartooning. I feel like they’re siblings to me in many ways. But there’re also some fundamental differences. I’m not an extreme pack-rat collector. I prefer a really minimal, stripped-down studio environment, which is basically the opposite of most of my friends. My drawings are just a lot more empty and clean in general than what most of my friends do.

[The hero of] “Hortisculpture” has had a very different life experience than yours. You were treated as a phenom early on, and you had a lot of anxiety that you would burn out, about whether you would still be well-regarded when you were 30, 35, 40. This is a guy who has never had anything like that from anyone.

No approbation, yeah.

Were you trying to depict someone with a completely different life experience in terms of his work?

No, no. Because in spite of all the kindness and encouragement and approbation that I’ve received over the years, it doesn’t diminish the fact that when I sit down at my drawing board I still feel in the same boat as this character. For all I know, what I’m doing is a complete embarrassment. Or that people are being nice to support me rather than being honest. Or that my children are embarrassed by what I do. All these thoughts are still a part of me. So it’s not like I tried to think about the inverse of my life path. It was, like all these characters, more about trying to find something in my real life within all these fictional characters.

Why did you use the newspaper strip for this kind of story? For me, a newspaper strip has a way of distilling an interesting moment while ignoring all the boring stuff in between. I guess most fiction is like that, but that experience is more heightened in a newspaper strip.

To me, it was a good way to show a passage of time while omitting a lot of the unnecessary scenes. It was also a way of trying to leaven a pretty depressing story. Each strip is a step in the guy’s downfall, but it’s done with a punchline, with a sense of humor about it. And that’s a balance of something I was trying to find throughout the book, of not hammering someone with the grimness of the it.

It’s not a weird subversion of the art form. I feel like “Peanuts,” which is probably my favorite comic strip, is an exact example of it. [It] shows the parade of humiliations of a character’s life, but plays them for empathy and laughs.

Illustration Credit: Adrian Tomine/Drawn and Quarterly

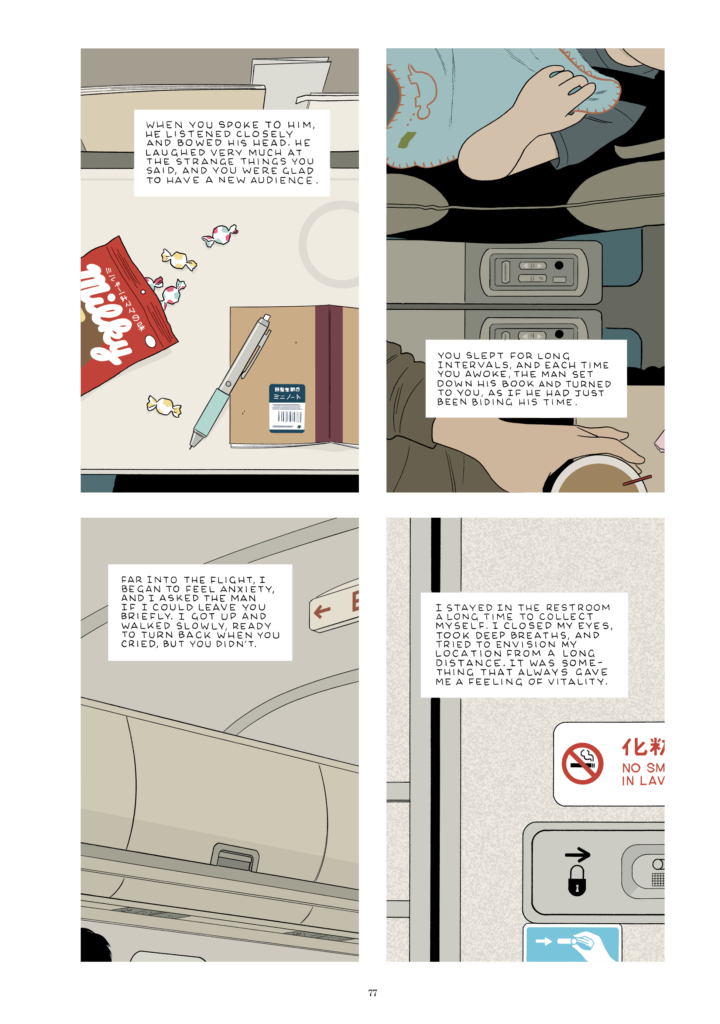

In your illustration work, as opposed to something like “Hortisculpture,” you want to create something someone would want to stare at. So that gives something like “Translated, from the Japanese” thickness as a story. Did that make you rethink the rhythm of the narrative?

Not the rhythm, but one of the things in illustrations is that you can create emotion or response from things other than people. At least, that’s my attempt. If you draw a little baby with tears coming out of its face, it’s pretty obvious what you’re trying to depict there . . . [I was] trying to find some weird emotional charge in very boring objects.

There’s a storytelling technique you use in “Amber Sweet” and “Invaders” that returns to what you were doing in the ’90s. It’s like a person telling you a good story in a bar.

I agree.

They were the stories that I liked the least. It’s not a fair criticism, but I’ll say it anyway. They felt a little less authentic to me. They felt like you were taking on a voice that you don’t have. Why did you go back to that style?

Well, part of it is the challenge. It would be really boring if I limited myself to writing in my own voice from my own experiences. I could build an entire career from that if I wanted to. There are plenty of cartoonists and authors who do that. It’s not really my interest. It’s hard for me to talk about, because this is coming up a lot as I’ve been promoting this book. And I don’t want to be too defensive or too explicit, but I would just like to suggest the possibility that some of the inauthenticity or what some people perceive as errors or missteps have something to do with the person telling the story within the story, as opposed to me the artist. And there’s some of that which is done intentionally. There’s probably some that isn’t. But so far I haven’t really heard from anyone who read those stories in the way that I intended.

Philip Roth has a line that writing fiction is like wearing masks. Did you find that that was something you were trying to accomplish in writing those stories?

I think I’m trying increasingly to create those masks because there’s a tension for me artistically between becoming a more private person, but also wanting to do work that is personal and introspective. If I had it my way—not just because I’m a lazy guy who likes to stay home—even artistically, I would prefer not to do any promotion for the books. I would prefer not to do interviews. Especially when Shortcomings came out, I wished to God I never published a photo of myself, because I drew the character who looked a little bit like me and that led to a lot of mental connections for readers that I thought were kind of a distraction. It is fun to make up characters and write from their voice, but a lot of it is an attempt to recede further behind the curtain as a person.

Paul Morton has worked as a cultural journalist in Vietnam, Bulgaria and Latvia. He also completed a Fulbright fellowship in Budapest, where he researched Hungary’s communist-era animation industry. His interview with Marvel Comics writer Brian Michael Bendis appeared in Ultimate Spider-Man: Ultimatum. He currently lives in Seattle where he is a Ph.D. candidate in Cinema Studies at the University of Washington. He can be reached via email at [email protected]. You can also read his blog My Thought-Dreams.

This post may contain affiliate links.