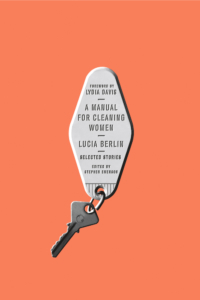

“In the deep dark night of the soul the liquor stores and bars are closed.” This is the first line of “Unmanageable,” the story which throbs at the unforgiving core of A Manual for Cleaning Women, a new, posthumous collection by Lucia Berlin. Not much happens in “Unmanageable.” It is night, and an alcoholic is awake. The pint bottle of vodka under the bed is empty. In two hours, at six, the Uptown Liquor Store will open; between now and then, there is fear, fear and desperation. “Trick is slow down your breathing and your pulse,” the protagonist thinks. “Stay as calm as you can until you get a bottle. Sugar. Tea with sugar, that’s what they gave you in detox.”

The drunk’s tale is a familiar one, its outlines recognizable to anyone who has a read a work of mid-century realism (Cheever’s “The Swimmer”; Exley’s “A Fan’s Notes”), to anyone who has had a drink, and then another, and then one too many, and woken up hungover, and tried to remember the last time “morning” was not synonymous with “headache.” First there is fun, which shades into recklessness, which shades into need. With need comes abandonment: Families fracture; friends flee. Abandonment fuels destitution; destitution, finally, is transformed into redemption. The shock of “Unmanageable” — the brilliant shock of Berlin’s collection as a whole — comes a page and a half in: “It would take her three quarters of an hour,” the protagonist thinks, calculating the walk to liquor store. “She would have to run home to be there before the kids woke up.”

***

What the drunk’s tale — the male drunk’s tale — too often elides is the way life, the mundane day-to-day of laundry and sandwiches for school and the gas bill, continues to demand of the drunk what it demanded of him when he was sober. For in the male drunk’s tale, these are responsibilities all too easily fled. This is the truth that Berlin’s collection reveals: The female drunk, “hyperventilating,” worrying that “if she didn’t get a drink she would go into DTs or have a seizure,” must also always run home to be there before the kids wake up — as the male drunk does not.

Even a masterful account of male frailty — Leonard Gardner’s Fat City, for example, a potent noir that NYRB Classics will reissue in September — will, in the wake of this realization, read as a kind of evasion. At the center of Gardner’s novel is Billy Tully, a washed-up boxer. When Fat City opens, he is living in the Hotel Coma, outside of Stockton, California. “He had lived in five hotels,” the reader learns, “in the year and a half since his wife had left him.” Tully’s marriage produced no children, and without his wife he finds he can “not get up in the morning.” Already he has lost two jobs, his car. He feels, “the guilt of inaction, of simply waiting while his life went to waste.” “No one was worth the gift of his life,” he laments, “no one could possibly be worth that. It belonged to him alone.” And yet, “he did not deserve it either, because he was letting it waste. It was getting away from him and he made no effort to stop it.” Without a wife to come home to, without children for whom he must provide, “He did not know how.” By the end of the first chapter, Tully is listening to coughing from across the hall and deciding “It was time to change hotels.”

He can change hotels, and he does, and not for the last time, for he is beholden to no one. This is its own kind of tragedy, testament to the damage one is capable of doing to oneself when no one is looking. But it is a tragedy born of freedom. Berlin’s stories examine the consequences of living as if one were free when one is, because female, necessarily not.

Not every story in A Manual for Cleaning Women, which selects from Berlin’s eight previously published (and criminally under-read) collections, is about an alcoholic, but almost all are about women in some essential way alone — unmarried, divorced, widowed. Many are about women both alone and depended upon — that is, single mothers. Reading, certain elements recur: an early childhood in mountain mining towns; Catholic school; an adolescence in Chile; four sons; divorce; odd jobs (cleaning woman; emergency room nurse); detox. That these elements were a part of Berlin’s actual life is true; it is also beside the point. For Berlin’s stories, in their specificity, speak to a female universal: A woman’s life is never merely her own. It also, always, belongs to her husband to — especially — her children. “Look at your drunk self!” a son tells his mother in “Let Me See You Smile.” “Who are you? What about my brothers? Dad and his girl are on cocaine. Maybe with you they’d die in a car wreck or you’d burn the house down, but at least they wouldn’t think drinking was glamorous. They need you. I need you.” In “Carmen,” a woman goes into labor immediately after smuggling heroine across the border for her boyfriend. “Hot water gushed down my legs onto the carpet. ‘Noodles! My water is breaking! I have to go to the hospital.’ But by then he had fixed. The spoon made a clink onto the table, his rubber tube fell from his arm. He leaned back against the pillow. ‘At least it’s good shit,’ he whispered. I got another contraction.”

Women, in Berlin’s stories, are not necessarily more reliable but they are — in a way the men cannot be — peers. In “Tiger Bites,” “Lou,” nineteen years old and four months pregnant with her second child, returns to El Paso for a family reunion with her ten-month-old Ben in tow. Her cousin, the flamboyantly beautiful Bella Lynn, greets her at the train station, and soon Lou is relating her “short sad story”: Ben’s father, Joe, has left her. “That was the last straw for Joe,” she says, “me having another baby.” Bella Lynn promptly directs her to a Mexican abortion clinic and gives her five hundred dollars in cash to pay for the procedure.

***

It is infuriating — reactionary, even — to think of “woman’s work,” the unpaid, unacknowledged labor required to keep up husband and home, as a kind of blessing. But perhaps, for the addict, it is — or can be. In its unfairness it can act, Berlin’s stories suggest, as a kind of inviolable border, allowing one to sink this far — going to a liquor store at six in the morning; counting a pile of coins on the counter so the cashier will hand over a pint of vodka — but no further.

Then again, perhaps the conclusion to be drawn is a more ambiguous one. In “Tiger Bites,” Lou doesn’t get the abortion after all. Forced to stay in the clinic overnight, she helps the doctor by translating from Spanish to English for a young, anxious, American girl whose mother has passed out drunk. Her decision and her kindness imply a version of freedom inextricably linked to responsibility. Berlin’s protagonists want to be better than they know themselves to be; for this reason, they occasionally embrace gendered strictures, hoping that the pressure of existing within them will force change.

The most painful moments of A Manual for Cleaning Women is when that hope proves unfounded. At the end of “Unmanageable,” the unnamed female protagonist goes home, faces her children. Her son Nicholas’s first words to her are: “How in the hell did you get a drink?” A man, perhaps, is not required to look at his children at half past six on a weekday morning, not required to see in their faces that they know he is drunk, not required to hear them ask how in the hell it happened. But a woman can get used to it. The kids eat breakfast, gather their books and backpacks, kiss her goodbye, and head out the door. “She waited until the bus picked them up and headed up Telegraph Avenue. She left then, for the liquor store on the corner.”

Miranda Popkey is the assistant to the editor at Harper’s Magazine. She has been published in, among other venues, The Paris Review Daily, The New York Observer, and The Oyster Review.

This piece originally appeared in the Full Stop Quarterly Issue #2. The Quarterly is available to download or subscribe here.

This post may contain affiliate links.