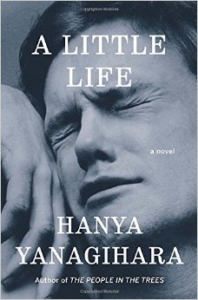

Hanya Yanagihara’s new novel A Little Life emerges between the contemporary “life novels” (of Ben Lerner, Tao Lin, Shelia Heti, Heidi Julavits, and newly imported stars, Elena Ferrante and Karl Ove Knausgaard) and a much older model of fiction, situated firmly in the 19th century: that of Dickens and Dostoevsky.

The “life novels” of today seem to hew so close to life as to cut into it. Often favoring qualities like minutia, repetition, stasis, neurosis, they don’t tell a story so much as narrate events. Live stream them. There seem to be generous and ungenerous ways of looking at this moment.

You might choose to see this attention to life as a refreshing return to relevance or contemporaneity in fiction. Or the writers I listed could represent an exhaustion of imagination, the final triumph of mundane lived experience over fictional invention.

In that case you might favor the second category, the Dickens/Dostoevsky ticket. A novel like that is much more plotty. Traditional. Event-laden. If they weren’t so firmly rooted into culture and curricula, the characters and drama would seem exaggerated, even melodramatic.

Yanagihara’s book takes the sense of the contemporary from one, and its grandiosity and stakes from the other. The result is a powerful and often painful story, one that harkens to the novel’s original mantle of presenting a life in full, and the struggle of individuals against both social restrictions as well as their pasts.

This is not a novel from life (or at least not explicitly so, like it is for the autobiographical fiction of those above) but it somehow feels like one. It could be said to render a great service and example to that model, namely imagination, the conceptual leap over one’s own direct experiences — and the invention of characters as opposed to narrators or personas.

But this book also works via exaggerations, projections. Its sense of contemporaneity is mingled with an out-of-timeness. In much the same way it operates via an older model of fiction, it operates via an older model of friendship.

How can friendship feel both so abundant and so rare? Henry Adams said that one true friend in life is already plenty, two is miraculous, and three almost unheard of. In that sense, and many others, Yanagihara’s four young men would prove exceptional.

They are college friends: Malcolm, a privileged, multiracial Upper East Sider, J.B., the only child of Haitian immigrant parents, and Willem, the orphaned, white Midwesterner.

Jude, the fourth of the group, is called “the Postman” by his friends in college (he is post-race, post-gay, etc.). Jude is a sort of cipher character. His friends all have carefully elucidated backgrounds (racial, sexual, familial, professional/aspirational) from Yanagihara. Jude only has scars. He is beset by an unspecific injury, and avoids discussion of his past.

The book, for its first fourth (which alone consists of 150 plus pages) often reads like a traditional coming of age novel, albeit split among four young men rather than one central narrator. Yanagihara has great insight early in the book on art, ambition, and what could be called the “New York model,” the modern hustle known to those with creative ambitions. This all creates a fantastic sense of nostalgia for the ongoing present:

But these were days of self-fulfillment, where settling for something that was not quite your first choice of a life seemed weak-willed and ignoble. Somewhere, surrendering to what seemed to be your fate had changed from being dignified to being a sign of your own cowardice. There were times when the pressure to achieve happiness felt almost oppressive, as if happiness were something that everyone should and could attain, and that any sort of compromise in its pursuit was somehow your fault.

Again on New York and ambition: “Only here did you feel compelled to somehow justify anything short of rapidity for your career; only here did you have to apologize for having faith in something other than yourself.”

So while this book says many true things about ambition, career, friendship, and maleness, it does so in a way that often feels more allegorical and archetypal than actual. There’s a largeness to these characters. They are so suffused with life, with pain, pleasure, intelligence and ambition, that they occasionally feel unreal.

With our new “life novels,” we seem to be accustomed to both a literature of ambition and the precise science of failure. It feels unfamiliar to concern ourselves with four attractive, successful young men. And yet, Yanagihara is quick to temper these characters’ outwardly successful lives with trauma that the post-Recession literature of failure could hardly imagine. These men easily gain the world, but a few of them are in great danger of losing their souls.

The book is certainly interested in the characters’ groundedness in the social, cultural, and professional spheres: career, race, class, sexuality. But over and above all of these things is the difference that Nick Carraway noted in the The Great Gatsby: “. . . it occurred to me that there was no difference between men, in intelligence or race, so profound as the difference between the sick and the well.”

The book, at roughly the halfway point, becomes Jude’s story. As more of his traumatic past is revealed, Jude becomes a successful lawyer, but he suffers from abusive relationships, coupled with intense self-hatred and self-harm. In her attention to Jude, Yanagihara highlights shame as a fundamental category of contemporary life. Shame, self-abnegation, and violence are all part of a kind of broader sickness Jude suffers from — and in his mix of stoicism and suppression, his high-functioning denial, his desire to eliminate the past as well as himself, this often feels like a specifically male picture of self-hatred and reinvention.

The drama then consists not in the life and fortunes of a character, but in Jude’s ability to accept love and care. His relationship with Willem is the novel’s deepest and most acute rendering of male relationships. But that kind of care it is also alien to him. The unarticulated answer to pain (and indeed, evil) is friendship. The central and universal struggle she articulates are Jude’s attempts to normalize or acclimate himself to real life, to accept love and care despite his conviction that he is bad and essentially undeserving.

The book, in its scope and size, uncovers something vital about that connection between adult life and duration, but it does that without appealing to a strictly mimetic relationship with duration or repetition itself. Rather than narrate characters making breakfast, or checking email, Yanagihara measures the business of their lives with the metric of love.

Charles Thaxton is a freelance writer living in Somerville, Massachusetts. His Twitter is here and his Tumblr is here.

This post may contain affiliate links.