This piece originally appeared in the first Full Stop Quarterly. The Quarterly is available to download or subscribe here.

In his 1955 essay “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” the Situationist theorist Guy Debord describes a new approach to urban space, one primarily interested in the political and aesthetic possibilities of movement, play, and ambiance to liberate city dwellers from the deadening effects of late capitalism. He argues compellingly for the revolutionary power of the pedestrian — how the simple act of wandering can transform bourgeois materialism and “the imperatives of Coca-Cola” into something radically refreshed: the city as game, the city as play box. Debord called this concept psychogeography, and the dérive — literally “drifting” — was to become the primary vehicle of psychogeographic practice. The dérive asks participants to forget their typical motivations for walking — that is, work, leisure, and the relation between the two — and instead allow the city’s terrain to create its own attractions and encounters. By merely wandering, the dérivist frustrates the spatial logic of capitalism, in the process discovering new currents, fissures, and vortices of possibility within a deeply familiar space.

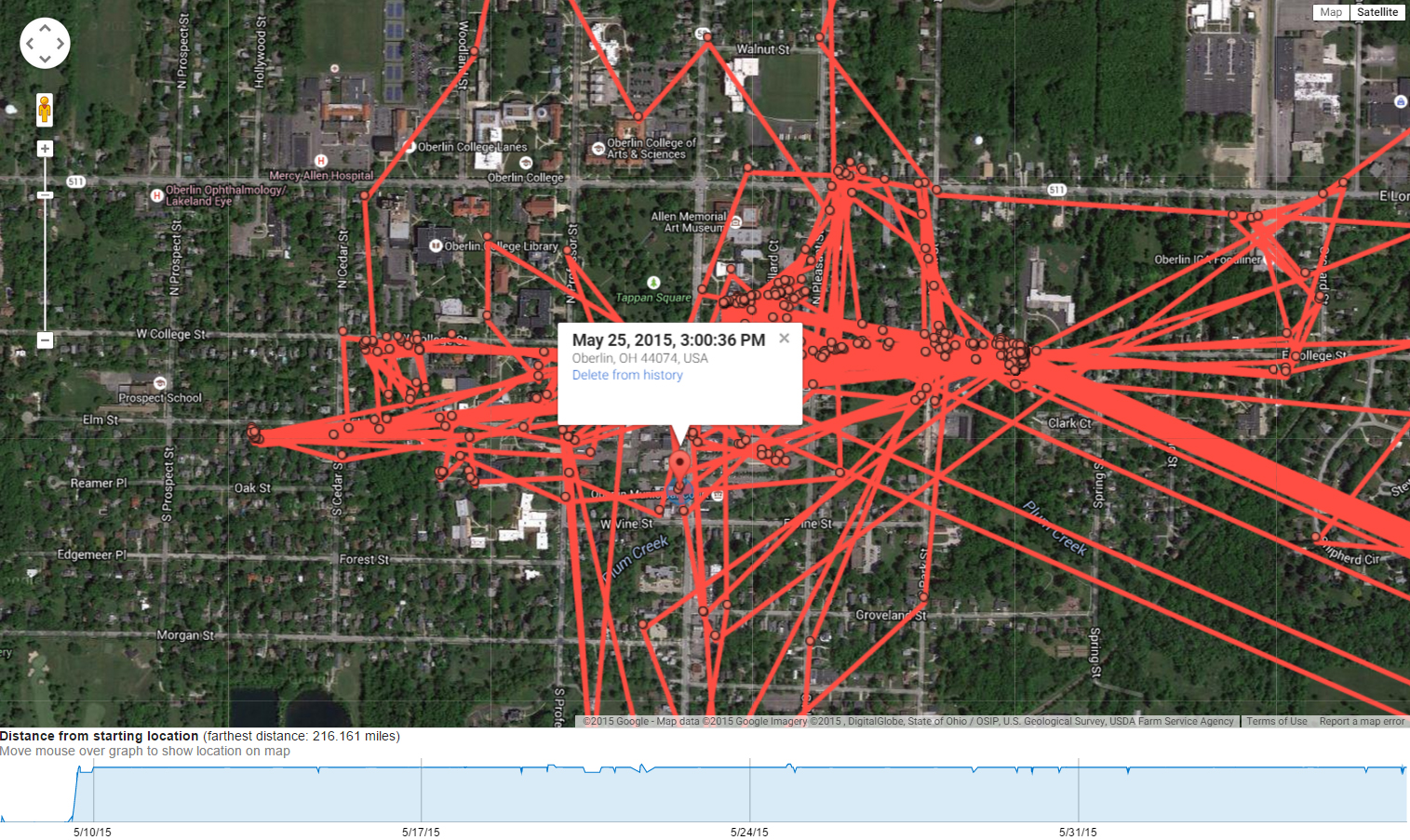

There’s something charmingly twentieth century about the dérive, of a piece with Surrealist Exquisite Corpse and Jarry’s ‘Pataphysical work. Never before or since have games been integrated into intellectual and aesthetic action with such disruptive intent. And though we may be a long way removed from the roiling midcentury moment when art seemed like it might reshape the world, I believe there is still much remaining in the dormant practice of the dérive to rattle and instigate in 2015. A new kind of dérivist is needed, one aware of both the implicit organization of space as a funnel to consumption, and the more recent development Debord probably couldn’t have imagined in 1955: that of infinite surveillance, tracked movement repackaged as data currency, and a disturbingly effective brand of predictive analytics.

In light of these developments within the urban panopticon, it would seem psychogeography is in need of a new theoretical model wherein space and our relation to it takes on a virtual dimension, one capable of articulating a subversion of surveilled space. And however that subversion ends up manifesting, the body will necessarily play an integral role in the process. After all, it is the body that is captured in endless grainy hours of footage, the body that is herded into tidy pens of consumption, the body that carries and acts out the data collected with regard to its own behavior. The dérive is interesting to me then, first and foremost, as a way of reconstituting the body as a site of destabilized meanings and radical aesthetic and political potential. With this in mind, where can we turn for inspiration and solidarity, to say nothing of new excursions, dreams, adventures, and maps?

This need not be a grimly sober project. On the contrary, the dérive is at least as much about the joy of ambulatory freedom and what Debord calls “playful-constructive behavior” as it is about protest; or, rather, the two, as it turns out, are here inseparable. Already there are heartening signs of life in the burgeoning field of neo-dérivism, complicating and supplementing twentieth-century Situationist thought and practice. Witness the jogger who uses her own GPS data to draw city-sized dicks over San Francisco, a transgressive-aesthetic use of data that earned her broad internet acclaim and reversed the relation of power between the self and its collected data set; or artist Paulo Cirio’s project Street Ghosts, which pastes life-size posters of individuals captured by Google Street View back onto the physical locations where they were unwittingly photographed, recontextualizing the surveilled images as “casualties of the info-war in the city, a transitory record of collateral damage from the battle between corporations, governments, civilians and algorithms.” In the daily urban “info-war,” in real and digital space, the body’s presence and its potential for random and defiant joy dovetail nicely with dérivist possibility — a synthesis of empowerment and play.

Literature, too, is rife with paradigmatic dérivists. Leopold Bloom’s psychogeography of dear, dirty Dublin, with its emotional and temporal resonances, its deep pockets of memory and meaning, would look nothing like a map of the city torn from a guidebook. Baudelaire wrote at length on the possibilities and practices of the flâneur, the wandering poet-artist of kaleidoscopic urban space that so enraptured Walter Benjamin in his seminal The Arcades Project. In Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, Consul Geoffrey Firmin disintegrates within an inebriated mapping of both soul and space, in the process creating an indelible vision of Quauhnahuac that exists nowhere outside its pages. The immortal literary works haunt us in such a way that they can go about the business of what Debord calls “the correction and improvement” of maps. In cities, towns, parks, and promenades, we’re able to perform psychic overlays transmitted via literature, transforming actual space and investing it with pungent, vicarious experience. The well-read dérivist sees space doubly — a species of aesthetic haunting.

But whether the dérive is practiced aesthetically or politically (or, as is often the case, a felicitous joining of the two), it is the notion of imagination — the rich whimsy of play — that seems most important to me. Play is inimical to control, averse to compulsion and ideology. The spaces we inhabit are so often invested with an implicit goal — eat, buy, watch, be watched — that we can become immune to the beautiful and hazardous opportunities we’re afforded as possessors of bodies. At the heart of the dérive is what Debord calls a “technique of locomotion without a goal”; the possibility of practicing this technique in urban (or suburban) space, at least under the auspices of industrial capitalism, is impossible without a conscious break in the accepted spatial logic. The notion of play — wrapped in the strange, chaotic, jubilant cloak of the dérive — can serve as that break: a way of remembering that roads go more than two ways, that fences can easily be leapt, that meaning is never permanently affixed to space but rather awaits the abrogations and sanctifications of individual experience.

The dangerous passivities of space surround us, more or less constantly. Signs, arrows, hedges, painted lines, paths, rails, blockades, gates, turnstiles, barbed wire — each a reduction of oneself, one of a billion tiny resignations that comprise a collective and largely unconscious numbness. To live, here and now, is to be corralled. But in daring to apply the psychogeographic ideal — in embracing the potential of the dérive — drifting becomes a form of beautiful resistance: the pedestrian recast as physical poem.

This post may contain affiliate links.