I.

At Aunt Mim’s funeral in Sonoma, California, my Uncle Bubba and I are laughing about how our 95-year-old negro great-aunt’s death certificate lists her race as “white.” Bub turns to me, a plate of hors d’oeuvres balanced in his palm, and tells me about a recent car accident Granny’d been in. “And then,” he says, “I can’t get over this one. The very next day after she got into that one, she goes and gets into an accident with your car! What did you make of that?”

At first I thought Bubba, a bonafide ne’erdowell, was yet again pulling my leg. I hadn’t heard anything about my car being damaged. I’d been busy with work and hadn’t been home for some time, but surely no one had said anything about a banged up sedan. Momentarily forgetting that I was attending a funeral reception, I went up to my grandmother — who was sipping champagne — and asked about the incident.

“Damn Bubba for ratting me out. But I got it fixed, mind you. $1500. Looks brand new.”

All this to say that Granny’s sitting shotgun while I drive to Richmond. Three and a half months have passed since Granny’s last surviving sister, my Aunt Mim, died at 95. Just a few days before Easter Granny sent me a text message that read: “I want to see my home.”

I was supposed to know — and did — that I was to drive her to see her old Virginia home.

Our road led south to an old place. It’s 150 years to the day that Richmond was invaded by Union forces, and in the course of our weekend there we’ll find soldiers in Yankee blue and Rebel gray marching throughout the streets, reenacting the battle that will bring the Confederate capital to defeat.

No more than an hour into our journey, Granny turns to me and tells me about a conversation she had with my mother before she left.

“I told your mother I was going to Virginia. Told her I’m hoping not to get lynched. She told me to stay away from tall trees.”

I laugh beside myself, beside the woman seated next to me. But just outside of Richmond, with the night drawing in, Granny turns serious.

“Has the South changed much?” she asks.

“Well, it hasn’t and it hasn’t,” I answer her. She pauses.

“Do I need to be afraid?”

II.

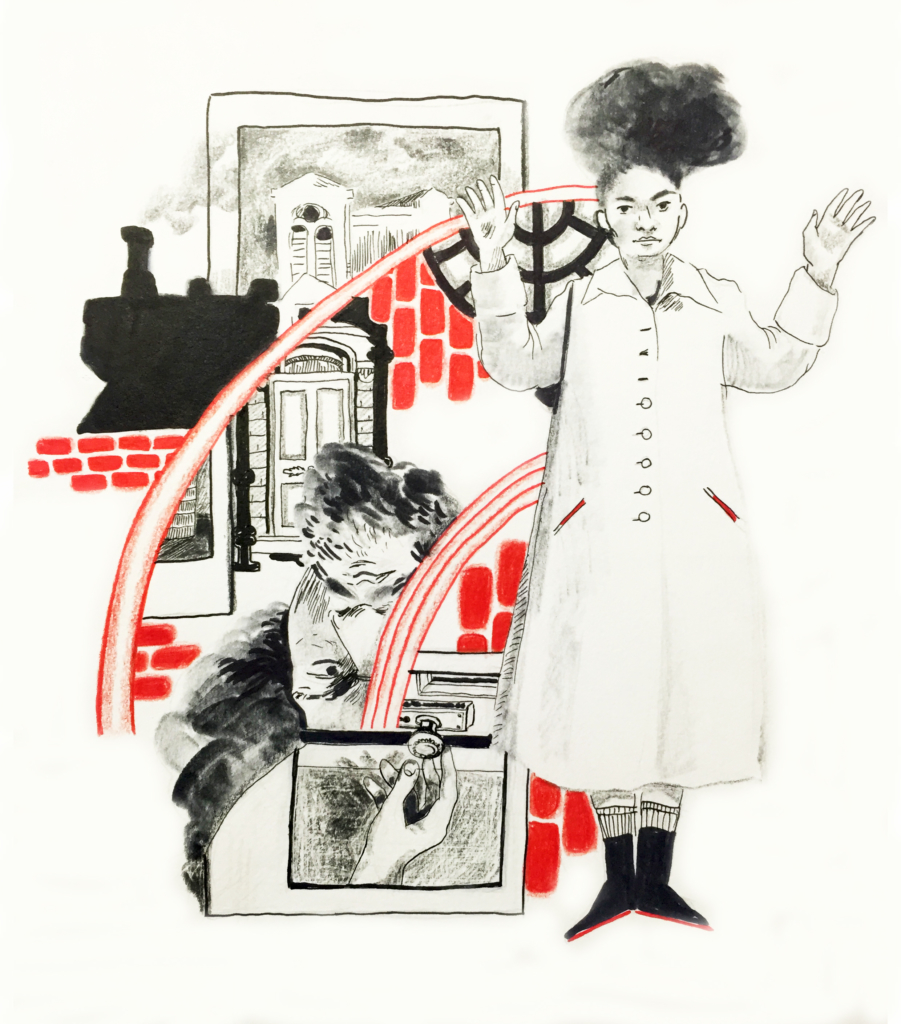

Occasional glimpses of the changing flora glance into sight, and I think of Lincoln’s marching army crusading to free the slaves who’d been tied to the clay and the seed and the hoe; the Rebel civilians role-reversing, absconding to the hills and the swamp at the not-too-distant brassy echoes of Union battle hymns, leaving their doors unlocked, their liquor undrank and their pipes half-filled. I see the slaves gathered at a tavern in Fredericksburg distributing their once-owner’s cash, taking a glass bottle of brown liquor from the polished shelf and toasting to the Yankees’ health. This scene is in accordance with a slave narrative my family harbored for decades, handwritten by a self-freed bondsman, John M. Washington, who, I think to myself, I must emulate by expressing, precisely, in comprehensive terms, what it is I have witnessed in my descent to the still-vexed South.

But this vexation is not limited to a region, I see now, as much as I wish to confine it to the margins of my nation.

By the time my grandmother returns to Richmond, all of her siblings have died and no one in the neighborhood of Jackson Ward remembers her. She’s last stepped foot inside her ancestral home — the home her grandfather built after he returned from serving Lincoln’s grand army — when she was seven years old. It’s been 79 years since she’s seen her birthplace. The home, long-ago sold to a private company, is now rented out by college students, but Granny’s knocked on the door and introduced herself to the young blonde boy who has answered.

“My name is Alice Robinson,” she says, “and I was born in this home 86 years ago now. My grandfather built it, and I’d like to see it once last time.”

The boy — he looks like a rock musician — is stupefied. He’s not puzzled, but he’s carefully considering how much cleaning he can get done. “That’s amazing,” he says. “I’d love to show you inside, but we had a party here last night.”

My grandmother, I say, has come 400 miles and waited eight decades and is not concerned with a few beer bottles. The boy heads inside to clean but returns just a moment later. “No amount of cleaning I can do now would tidy it up,” he says, apologizing for her home’s current state.

Crushed cigarettes are strewn on the floor, all mixed up with someone’s broken beer bottle. He shows us around, but the home has been refashioned and Granny hardly remembers a thing outside of the staircase. I picture her sliding down it, but consider that her well-mannered family would never have let such a thing pass.

“This is my home,” she says as we stand outside. “But I don’t remember much of it. I wish my sister was still here to see this and prompt my mind. I do, however, remember that water fountain there and the school across the street. Who is that a statue of?” she asks, pointing to a little park on the corner of Leigh and Adams streets.

That’s Bojangles Robinson, I tell her. The great tap dancer and minstrel man.

“A Robinson? He’s no relation of mine,” she says, and I have to laugh at the coincidental statue of the man with the wide grin who shares my grandmother’s maiden name. It’s long been a joke for my family members in the know — the ones who have been to see the ancestral home sometime between 1936 and now — that a statue of a Robinson stands just outside the Robinson family home. In fact, the statue was erected only in 1973, long after most of my family had fled for the North. But the plaque beneath the statue tells a story about Bojangles’s visit to Richmond in 1933, when my family still occupied 100 W. Leigh St. He was horrified when he watched little children run into the street to retrieve a ball. Immediately after witnessing the event he donated money for the neighborhood to erect a traffic light. In an artistic leap of faith, I saw, in that springtime evening, my grandmother as a four year-old girl chasing after her ball only to be saved by the intervention of a minstrel man.

III.

“And what’d she think?” my grandmother’s cousin Esther wants to know. Esther, who’s recently broken her hip, will be 98 in August, but she’s still reading at a pace that puts most pairs of younger eyes to shame. We’re sitting together in the Brooklyn rehab facility where she’s been for a few weeks now. I take out my phone to read from some of the writing I did while I was in the South, and scroll through the photographs I took with my grandmother out front of the old home.

“The house looks beautiful! Just like it did back then. You know, Dr. Du Bois stayed in that house until my husband’s father built a new place out on Frederick Douglass Court.”

“You know,” Esther says, “when my husband Jack was in his early 90s and dying, he only ever wished to return to Richmond. He’d sit at the window here in Brooklyn and say, ‘I want to see Richmond.’ So we made a trip, taking him to see the old home, drawing memories from his mind’s well. And when we returned to Brooklyn, he again sat at his window and said, ‘I want to see Richmond. I want to see my home.’ He had no recollection of having been there even a few days before. So we went back and toured the same places we had just seen a week or so before.”

There’s been some concern in the family that even Esther might be repeating herself. But at this point, I choose to recognize her retellings as a matter of emphasis, not forgetfulness. Esther, an ardent activist, and a former editor of Freedomways, an influential literary, political, and culture magazine, tells me all about Paul Robeson and Pete Seeger. In an effort to drive sales, artists Jacob Lawrence, Richmond Barthe, and Romare Bearden contributed covers gratis to Freedomways.

“Bearden’s parents or grandparents had been slaves to the father of President Woodrow Wilson,” Esther said. “Bearden himself looked Polish. He could have been anything.”

“Esther, after we visited the old Baptist church down in Richmond — we found the baptism records for most of the family, by the way — Granny turned to me and said, ‘What must they make of you not looking like any of us?’”

I’d been enraged. What must they make of me? Granny was the one who partly got me looking the way I do. What must they make of Granny! She’s the one who hasn’t said mum to a soul down there in 80 years. She’s the one living in Connecticut now, a Catholic convert. But Granny was quick to laugh before I unholstered my anger, before I saw she was just laughing at her own trickery.

“Some people are just not with the times,” Esther, nearly a century old, said. “You’re just like everybody else.”

As she lay there yet unable to walk on her own — perhaps she’d never walk on her own again — I considered her life in Virginia, her early days of marriage in Alabama, the decades she’d spent in New York. I was unable, or almost unable, to figure how she’d gotten from there to here and how I had become a part of her life. Our conversation flew away beneath time.

I was reminded of Ellison walking Harlem streets interviewing everyone for the WPA in the late 1930s. “Some of those interviews affirmed the stories that I had heard from my elders as I grew up,” he said. “They gave me a much richer sense of what the culture was. I might say it was like taking a course in history.”

IV.

I want my nation to take the shape of our gloried ideals, where every story becomes a myth for our founding principles. We’re only ever happy with a story at hand, a song for ourselves. But with this comes the recognition that America gives little quarter to her past brilliance; a condition of being, or a conditioned being, mired in archaic notions of what it means to be alive within our borders. Who are we? And what do we make of each other?

The questions came in droves when I returned from Richmond. I met a friend, Max, one weekend evening in Prospect Park. We made our way out using the projects above the desiccated tree line as our guiding stars to the park exit by Empire Boulevard. A bevy of fast food restaurants, but otherwise a food desert, a blight of benign neglect. A McDonald’s, a Burger King, a Checkers, a Dunkin Donuts with a sign outside announcing its grand re-opening, a Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen. We walked further down Empire, past the vacant-looking nightclubs along the road and the warehouse-sized laundromat. I’d never seen a white person in it. We made a left at the self-storage facility up Franklin Avenue, our substantial plumes of condensed breath just a step ahead of us in the cool spring night. The Ebbets Field housing projects, which lit our way from the park, rose like an urban megalith from the street below. Four thousand people were said to be living there, perhaps more judging by the sheer hulk of the thing. On the west side of the building, I’d broken an elbow one summer playing basketball against some of the neighbors.

At a bar nearby, Max settled in to talk.

He said, “Have you ever learned anything that you’re ashamed of? For so long I ignored what I thought might be lurking in my history,” he said. “That my mother is a German born in Venezuela. I tried to overlook the connection. That her father shot himself in his backyard. I was ashamed of that no doubt, and am ashamed still. I found his journals some time ago. And my fears were confirmed. He’d been a Nazi seeking asylum in South America. His journals were riddled through with antisemitisms. How could I be related to this man? I’m grateful he shot himself in the head, but that’s a man who held me when I was young. Who looked at me and held me. A goddamn fucking Nazi held me, Andrew, as an infant.”

His eyes were enraged, we spoke in hushed tones in the corner with our beer.

“Look,” I said. “If there’s anything I’ve learned, and I haven’t learned too much but I think this is what needs to be shared with you — if I’ve learned anything at all it’s that each of us is capable of anything. Human beings are capable of the worst dealings imaginable, it’s in our blood. I’m related to both a slave owner and his slaves. Evil is in your blood and it’s in mine, Max. Look at us! Who’s to say we would have been heroes in another time?”

“You’re not making fucking sense,” he said. “You’re not making fucking sense at all with that shit. My grandfather killed Jewish people, I saw that on one of the very first pages of that fucking journal and I’ll never get that out of my fucking head. That’s not me. I could never do the acts he wrote about. I wouldn’t even think of writing them up, making things like that up because I’d be so disgraced.”

V.

The reality of American life is no doubt stranger than fiction, and there aren’t enough writers to exhaust the plot possibilities latent in our nation. I spent my spring and early summer reading Ellison, preparing my history classes for our studies of the Civil War, but the news inevitably barged in on my attentions. We stayed up late watching the television, and in the morning the papers reported the riots in Baltimore, the killings across the States, and somehow, inevitably, my life trudged on amidst the furor. I read and thought about writing, but there never seemed to be enough time. There are certain events you can never gain perspective from.

I hate how well I slept in those weeks, the sleep of forgetting, because its rest was so delicious, so reassuring, that to wake and find our country still unresolved, still not yet worked out, was nearly crushing. Each morning I’d rise and recalibrate myself to this new, nightly forgotten landscape. What, I’d ask myself upon waking, would I tell my students today?

Before Freddy Gray became just another name, 11-year-old Deandra asked me how a spinal cord gets severed. “Do you think he was scared?” she asks me. Later I’ll consider how she’s the same age Granny’s uncle Morris was when he was killed by a group of white boys.

I became a teacher, in part, to answer these kinds of questions. I gave up a career in publishing to answer questions like Deandra’s, to share with her and her classmates what it is that I have learned (and have yet to learn). But, as the semester wore on into June, the giving of tests and grading of them, the typical end of the year outbursts from students and teachers alike, I faded into a routine. Life continued. I could race home from school only to sit at my desk and not write, so instead I’d visit museums and read in the library. A bar opened in my neighborhood. I was invited out, and despite the women, my mind was elsewhere. On occasion, I drank too much, but upon drying out, I remorsefully reacquainted myself with the novels I had put down. One morning, on a June day between sunshowers, I’ll kiss a girl as she boards the 3 train in Grand Army Plaza and nearly skip home past the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument memorializing the glorious Union effort.

When my mother visited New York for her birthday on June 17th, we visited the Met together and ate at a diner on the Upper East Side as old men walked by the storefront windows with their little leashed dogs and sinking asses. Mom had not seen me for some time, but she’d picked up a book I might like: Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston. At Grand Central Station, I could feel my mother refrain from kissing me on the lips before she returned home to Connecticut, and Granny. Heading back downtown, I stopped at my old publishing office to meet Lewis Lapham, my former employer, hoping that he might invite me for a drink in Gramercy.

We drank wine at a sidewalk cafe as I retold a story about Romare Bearden who strolled by a Parisian restaurant as Matisse, walking in for a meal, received a standing ovation from the entire bistro. Lewis asked my thoughts on the Rachel Dolezal scandal; this being the evening of the Charleston shooting — just hours before, in fact — when the massacre of the Beautiful Nine had yet to return our national conversation of race to urgent direness.

For a few days in June it seemed that we could laugh at the race-spectacle that was playing out in real time. But, as the news reports were filed, I remembered that when Ralph Ellison breathed his last in April of 1994, he shed a single tear. It was the month Dylann Storm Roof was born.

The people of this contradictory and violent, protean nation offended her principles yet again. I was surprised by those who were surprised. “Racism is a part of our DNA,” President Obama said from a radio host’s studio garage. And so we must radically re-vision what it means to be an American lest we face cyclical acts of racist recidivism.

We yearn to be free of a sordid history, to exist undeterred by a fetid past, but the irreality of what we have learned and witnessed encroaches upon our daily being. But, listen. You are here. You are now. And you have a story to choose how we will be. That is your privilege. Testifying to the allegorical dimensions of history takes a bountiful betweenness — ruthless rootlessness — to exercise the imaginative capabilities of Americans. We must see ourselves for what we are: an amalgamation of each other.

This post may contain affiliate links.