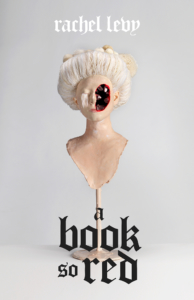

There are many ways to go about breaking realism; perhaps to get it where it would most feel it — the bitterest of cuts — would be in its marriage plot; that’s one of its major guts! Rachel Levy, in A Book So Red, lays this gut out on a barn floor and gives it 88 new notches, one for each page of this short but powerful novel.

Literary critic Naomi Schor defines realism (particularly in the 19th century) as “a representational mode wedded to the marriage plot and the binding of female energy.” To rewind, Descartes wrote, “I think, therefore I am” — Cogito ergo sum — in 1637. This is logic that invests in the contained and progressing consciousness of an “I,” and it also implies that language can represent experience. Seemingly seamlessly, ergo the oily tentacle. Though Barthes warns, “[T]here is no antipathy between realism and myth.” Myth being intrinsic to these representations — myth being problematic, to say the least, for Barthes, in its oily simplicities, its pretense of natural order. Marriage being full of this pretense, presented often as a completion of the plot, end to all confusion, the completion of people. You complete me. What is at stake? Our enjoyment of complexity, opacity, difference, different lives, lesbianism . . .

A Book So Red begins with divorce — “We were in Munich, celebrating his divorce.” The speaker interacts, in a series of short exchanges, with a male-pronouned thing who later becomes the name “Horst.” They dialogue in brief bursts — the pages fly — about divorce, about damp sausages and the brightness of Germany’s sun, though as these conversations proceed they are interrupted by new names — the appearance of things like “Bethany,” and “Lizbethitis”—“because she was one who begged for a cure.” Speaker plus Horst cannot complete anything. They put each other down. They think about other things. They aren’t in causal communion. Levy’s rhythm is one of undercutting, and what she undercuts most is the ergo, the smooth logic of realism (she does this manually, with blunt negation):

It’s called a penis.

It was hard. I had no idea it was there.

“I’m coming,” he said, and it had nothing to do with me.

The speaker hopes Horst will come with to Auschwitz — “‘You know what?’ I said. ‘We have so much in common. I’ve never been to Auschwitz. You’ve never been to Auschwitz. Let’s go together!’” What to make of this desire? This interest reads actually as earnest: “To Auschwitz: would he come?” It is the I-thou-iest question. In a book that takes things and cuts them with such constant ferocity, levity, and delight, this desire sounds real — Will you come with me to Auschwitz? Can we share in this sign of total obliteration? Will we together understand the world as gone (The world is gone, I must carry you, Paul Celan)? Hope in co-mourning, in co-horror, I want to touch you through Auschwitz, through this end.

The “I” constantly triangulating its desire . . .

Love was painful: a stapled nipple.

Love was tender: a warm washcloth to the nipple.

Love was generous, and we had so much to give to Horst. We had so much to share with Horst, the staple and I.

Levy torques, tortures, cliché — “I have so much to give,” like a line unspooled by machine from a bachelorette on television, now fucked in its pronoun, something we give, this love, staple and I, I and thou staple, to Horst. Changing the automatic language of cliché, of rote representation, of reality television, changes — explodes, opens — the possibilities for desire. Desire expands, complicates (to staples, to other women) when you fuck with clichés.

Levy’s style harkens back in content and in form to Flaubert, for whom there is always something else, outré-desire, outré-horror, très-Bataille, on the outskirts of plot, Madame Bovary’s marriage plot — but then, he does inskirt these things with meticulous clausal insertion. Surgeon. In this example, Flaubert paints a scene of pastoral charm, only to inskirt this oozing shit:

Rouault must be one of the well-to-do farmers. There was with him only his daughter, who helped him to keep house. In the stables, over the top of the open doors, one could see great cart-horses quietly feeding from new racks. Right along the outbuildings extended a large dunghill, from which manure liquid oozed, while amidst fowls and turkeys, five or six peacocks, a luxury in Chauchois farmyards, were foraging on the top of it.

This paratactic mixture of manure and peacocks undercuts F’s theme of a pastoral romance. He slices some shit into his plot, if to fuel then also to soil, to foil, the desire. The middle of A Book So Red extends a series of farm fragments involving, like Madame Bovary, a farmer’s daughter who is ripe for marriage, as was Emma: “I want to be clear. I was raised on a dairy farm. I was old enough to marry. At nightfall, Father gave me a mug of warm milk.” Where F performs the adulterous content of his text with sentences that also philander, clauses unbeholden to each other, tones akimbo, L undercuts the marriage plot with other, extremely otherous, content. Her farmgirl does not advance in romance but toils in thoughts of the Holocaust:

cat·tle, n. Property.

deer, n. Woodland animal.

Clear-cut, twofold.

The God of Adam cleaved deer and cattle, forest and farm. He is a deer let loose, he gives us our words. The herds of cattle are perplexed! He makes my feet like the feet of the deer and sets me on high places. He was driven away from men and fed grass like cattle.

I practiced good penmanship.

The Yiddish word for “deer” is “hirsh.” The men of that name were fated as cattle, corralled, slaughtered.

It was impossible to be precise.

But one must choose a side. I must choose.

A Book So Red evades capture by marriage and divorce plots, both, both of which are traps, false choices — (“First capsize the bathtub. Then, as if trapping a beetle beneath a cup, place the tub directly over the marriage bed.”) — landing perhaps on an out, a lesbian partnership — “And then there was a woman.” But this, too, is unstable — the love, like any word, slips, triangulates, activates something altogether else: a staple, a shoe, a glass, an emberous nub of lipstick. I find this text hopeful, as hopeful as its visit to Auschwitz. Hopeful in what it acknowledges is gone, and if it evades old modes, in what it evades towards — often to sound and texture, a writing that is alive to the slowness, the a-romantic ardor, of its objects, a stew “held to bright chunks of carrot like aromatic glue,” a realism flayed — manually, with guts — of its many myths.

Caren Beilin‘s novel, The University of Pennsylvania, came out with Noemi Press this past November and her fiction chapbook, Americans, Guests, or Us, is available from DIAGRAM/New Michigan Press.

This post may contain affiliate links.