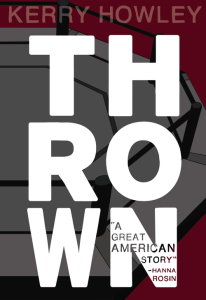

The first sentences of Kerry Howley’s debut do not dispel the impression one might have formed from the back-cover blurb of gonzo reporting on mixed martial arts, the popular fighting style with a byproduct of blood and a reputation for brutality. A few pages deep, however, as welterweight Sean Huffman greets fifteen minutes of blows to the face, transcendence arrives and a different sort of book announces itself: “It was as if someone had oil-slicked my synapses, such that thoughts could whip and whistle their way across the mind without the friction I’d come to experience as thought itself.” So begins a marvelously written, hilarious, and strange account of Howley’s three years as a spacetaker to Sean Huffman and then-emerging fighter Erik “New Breed” Koch.

Spacetakers are to fighters what groupies are to bands or entourages to movie stars. Because they “belong to the fighter and not the fight,” their principal duty is not locker-room encouragement but hanging out. Thus Howley’s double allegiance is a matter of some awkwardness, since her presence is required in two places at once. Sean is thirty-two, old for a fighter. His love for fighting is unsullied by ego; perhaps because he doesn’t care more about winning, it competes with those other loves for marijuana and Hardee’s Thickburgers. A decade Sean’s junior, with no competing passions, Erik is aging into rather than out of his talents. His nickname “New Breed” refers to his membership in the generation that grew up learning MMA as a unified sport rather than arriving at it upon one of its tributary martial arts. Erik struggles to leave his band of childhood friends and sparring partners in Cedar Rapids — a tightly knit crew known as Hard Drive — for the glittering metropolis of Milwaukee, where a coach awaits to take over his training from Erik’s self-taught brother.

The conceit of Thrown is that the narrator, the philosophy graduate student Kit, becomes obsessed with recapturing and studying the ecstasy she first experiences upon witnessing Sean welcome three rounds of face jabs. While Thrown is ostensibly nonfiction, Howley’s website describes Kit as “semi-fictionalized” (more on that later). Kit recalls the narrator of Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, her florid prose style straddling the brilliant and the bathetic, her solicitousness for her charges as paternalistic as it is admiring. With the false humility of the helpmeet she says, “Perhaps, when Sean finally made it, other fighters would come to recognize me as a small but crucial part of his resurrection.”

Yet her agenda for her spacetakees concerns not their success per se, but their ability to deliver ecstatic experience. If Sean’s resurrection only ends in another crucifixion, so be it: that might fulfill the conditions described by “Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Artaud, in which a disturbing ritual — often violent — rendered each of their senses many times more acute, as if the dull blunt body were momentarily transformed into a tuning fork, alive, as Schopenhauer put it, ‘to sensations fine and fleeting.’” One condition for such a spectacle is a certain madness on the part of its agents. Both Sean and Erik are willing to live outside the bounds of what the coarse among us might call a “normal life,” with wage labor and furnished housing. Normalcy is the foe of transporting spectacle. “It was Nietzsche,” Kit notes, “who said that a certain type of ghostly, corpselike wretch turns away from Dionysian revelry in a spirit of ‘healthy-mindedness.’” The healthy-mindedness that threatens the ecstatic potential of her fighters assumes the form of human attachment — in Sean’s case, to the unintended consequence of a two-night stand, Josiah; in Erik’s, to Hard Drive.

Our narrator antes up with her own madness. From the moment she leaves a phenomenology conference and stumbles in on Sean’s losing match, “the only phenomenological project that could possibly hold interest to me was as follows: Capture and describe that particular state of being to which one Sean Huffman had taken me.” As she spends more time spacetaking and less time on “bloodless scholastic exercises” the securities of her normal life drop away.

But now I must expend some lines on the generic quirks of Thrown. What of our “semi-fictionalized” narrator and her madness? If it is vulgar to quibble over the classification of a book as absorbing and sometimes dazzling as this one, still Howley — or Kit — has left me little choice. Then again, perhaps it is vulgar to pose as a philosopher seeking ecstasy when one is in fact a writer seeking material. The third chapter opens with an apologia:

“You,” my gentle detractors will say, “who purport to tell the stories of these real men, are but a work of fiction.” This I do not deny: I stand before you every bit as fictional as longitude and latitude, as the Roman calendar, as the 60-second minute, and I encourage you to dispose with all of these to the extent that they offend you.

The analogy being more literary than philosophical, I will spare it a rebuttal. Kit continues,

My (admittedly neurotic) progenitor . . . has never known a real person who saw herself with even passable clarity; never known a storyteller who could tell of a trip to the supermarket without self-gratifying sins of omission. All narrators, I say, are fiction. All. The reliable ones have the decency to admit it.

Here is one answer to the perennial scandals over the veracity of nonfiction books, the ado over A Million Little Pieces being one of the loudest of recent years. But the answer is more clever than convincing. Kit’s transparent unreality does not somehow render her narrative more believable. The effect is like that of a documentary created by Roger Rabbit: it’s hard to accept the live-action characters as real when they’re talking to a cartoon.

What nagged me about the contrivance was not so much that it compromised the purity of the Truth. What nagged me was that not portraying oneself may be the graver “self-gratifying sin of omission.” Thrown draws much of its urgency from Kit’s quest for ecstasy. It’s a neat trick: the stakes are clear; here is a narrator deserving of her fighters, who like them wagers her livelihood on a remote hope of triumph. Isn’t it deflating, then, to know that Howley is not deserting her professional duties through spacetaking but fulfilling them? Might it be to obscure the fact that she is spacetaking in order to write a book that she invents Kit — to endow the project with an importance she feels might otherwise be wanting? The dogmatic will object that any speculation about the motives of the author is idle. In creating such an avatar Howley invites speculation, however. Idle or no, suspicion creeps in.

Of course, as Kit and Howley differ, their agendas differ too. If the stakes for Kit are ecstasy at any cost, it may be no defect that Howley’s stakes are less clear. Perhaps what Kit’s hunger for human sacrifice shows is that the tragedy of MMA (as of many contests of greatness) is that its heroes are not its winners. Take Jonathan Brookins, one of the more memorable of a memorable cast of fighters. As a contestant on the reality show The Ultimate Fighter, he was “the first to describe his time in the house as ‘a journey of self-discovery.’” On the verge of winning the show, his chief concern was his humility. “I’m praying every day ‘Lord, don’t let this thing go to my head.’ Let me go home, ride my bike; let me go to the library.” Erik bests Brookins in an insipid fight. “This is what happens when you go on a journey of self-discovery,” Brookins remarks. “You don’t fight that well.”

This is the tragedy: goodness does not greatness make. If the book has a hero, which it doesn’t, he is Sean. As Sean disappoints Kit, he becomes the more admirable. Rather than sacrificing himself for the fight, he sacrifices the fight for his son. Erik’s egomania and monomania make him the fighter he is. Sean has neither and everyone adores him for it. His very ability to emerge unscathed from harrowing situations seems somehow to owe less to his good luck than to his good nature. While his love of fighting is purer than Erik’s — “I just like to feel things,” he says — his love for his newborn son is purer still. To Kit this human attachment is his downfall. But perhaps the curtain blows open and we glimpse Howley manipulating the strings when Kit sees a photograph of Sean holding his son and says, in irritation, “Someone with a less precise vocabulary might look at that picture and say that Sean was ecstatic.”

This post may contain affiliate links.