In Henry James’ late novel The Ambassadors, a man from Woollett, Massachusetts goes to Paris to pluck a young expat from his unseemly bohemian circle and restore him to Woollett, where he is to get married and become a fantastically wealthy businessman. Of what sort, we never learn. The man, Strether, arrives in Paris and expects to find Chad, the young expat, changed. And he is. But not in the way Strether had imagined; he appears not to be under a spell, or to have renounced his ambition, but to be a man who has grown mature and almost glorious, radiating an assured aura of completion. He’s become polished, a change affected by a woman, and also by Paris. Paris comes to affect Strether, too; the young Chad agrees to return home for a stint and Strether holds him back: he loves the city, and needs more time. The Ambassadors displays James’ usual attributes — the incredible alertness, the relentless dialectic between precision and equivocation, the careful brushwork in his depiction of intelligence — while also working as a comedy of expat life. You think it’s a stupid, dandyish waste of a life, until you experience its charm and change your terms.

In Henry James’ late novel The Ambassadors, a man from Woollett, Massachusetts goes to Paris to pluck a young expat from his unseemly bohemian circle and restore him to Woollett, where he is to get married and become a fantastically wealthy businessman. Of what sort, we never learn. The man, Strether, arrives in Paris and expects to find Chad, the young expat, changed. And he is. But not in the way Strether had imagined; he appears not to be under a spell, or to have renounced his ambition, but to be a man who has grown mature and almost glorious, radiating an assured aura of completion. He’s become polished, a change affected by a woman, and also by Paris. Paris comes to affect Strether, too; the young Chad agrees to return home for a stint and Strether holds him back: he loves the city, and needs more time. The Ambassadors displays James’ usual attributes — the incredible alertness, the relentless dialectic between precision and equivocation, the careful brushwork in his depiction of intelligence — while also working as a comedy of expat life. You think it’s a stupid, dandyish waste of a life, until you experience its charm and change your terms.

Theodore Roosevelt, writing in 1894, was immune to the charm. He knew exactly what American writers should do: stay home. James got the idea for The Ambassadors from William Dean Howells, a friend and critic who wrote his own modest novel, The Rise of Silas Lapham, about a businessman from rural Vermont who suffers from the standard anxiety of the nineteenth-century American nouveau riche: how to match up against the more cultured, more European east coast aristocracy. Howells went to Paris and gave a friend advice: “You have time! You are young! Live!” Youthful living, then as now, vaguely connoted going abroad, and James turned the quip into a novel. But Roosevelt wouldn’t have appreciated the sentiment. Going abroad as an American, for him, was not so much about enjoying youth as becoming “over-civilized, over-sensitive, over-refined.” “Thus it is with the undersized man of letters,” he wrote in his essay “True Americanism,” “who flees his country because he, with his delicate, effeminate sensitiveness, finds the conditions of life on this side of the water crude and raw.” Shots are taken at Henry James, the New Yorker turned naturalized Englishman, turning deviously into subtweets: “This émigré may write graceful and pretty verses, essays, novels; but he will never do work to compare with that of his brother, who is strong enough to stand on his own feet, and do work as an American.” William James taught Roosevelt at Harvard.

Colonialism seems always to trail the idea of the expat, and Roosevelt’s oppositions between America and Europe (masculine/feminine; novel/exhausted; industrious/aesthetic) convey a national anxiety dating back to British rule. America the fledgling industrial power had its own myth to build, and its own anxieties about that myth. It didn’t help that the American literary figures of the day — Howells, Dreiser, Crane, Norris — championed “democratic” American versions of realism or naturalism that had in part blown in on European gusts. But these writers stayed home, or were at least more unambiguously American. To live abroad, for Roosevelt, was almost to wish away independence.

For the past year I’ve been living in Shanghai, currently in a tiny 17th floor room amid glassy skyscrapers and previously on the densely forested campus of an international school that once, during World War II, doubled as a Japanese-run prison camp. Living abroad as an American today, during what we’re told might on the opposite end be the decadent autumn of American power, the stakes have changed. I don’t now feel like a traitor, but I do worry that I’ve accidentally become involved in a community of vacuous neocolonial frat boys, mostly suits but including the odd martial arts devotee, who play roles in a social scene that revolves around a sense of impermanence, a city shrunken into expat districts and elsewhere, and the chance, after taking advantage of affordable luxuries, to fuss luxuriously. This past summer one of my friends decided to leave and move to New York. The only time it made sense being in Shanghai, he once told me, was the time we walked into an empty bar and smoked a spliff with the middle-aged Chinese woman who owned it. Otherwise we hung out with expats. There are obvious reasons to live abroad — personal, financial, the chance to learn something, however limited, about an increasingly globalized world — and yet sometimes they seem preposterous when placed beside the thought of going home, though for me that likely means moving to a city I’ve never lived in and doing my part to gentrify it. It’s hard as an expat to see your own special mix of blundering and privilege and not think of it as grotesque comedy, but it’s also hard, for me at least, to figure out where to live.

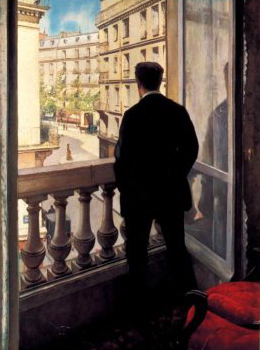

At the end of The Ambassadors, Strether, Woolett’s man in Paris, has failed in his duty and reversed course. He insists that the young expat not go home; he must stay in Paris, forget the money and career, and remain alongside the woman, Madame de Vionnet, responsible for his improvement. As for himself, Strether takes in the French countryside, he walks the streets and pauses “in the pleasant cool draught of the porte-cochére,” he smokes on terraces and dines in the light, fancy Parisian way: one glance at his futzing and you would have “every ground for scandal.” He decides it’s time: his career is nearly over, death or something as quiet is approaching, and Woolett waits. He has to go home “to be right.” It’s a conservative end, but also a selfless, fitting one (“shaped like an hourglass,” E.M. Forster said, not altogether approvingly), and it doesn’t seem any more conservative than its alternative: piddling around Paris, as an expat, in profligate aristocratic style. Two alternatives — both conservative. Maybe the real value of expatriation is in working around these — having to face the romantic thought of living abroad, and the romantic thought of coming home, and finally realizing it’s a little dramatic to have thought romantically of either.

This post may contain affiliate links.